Tea With A Warlord

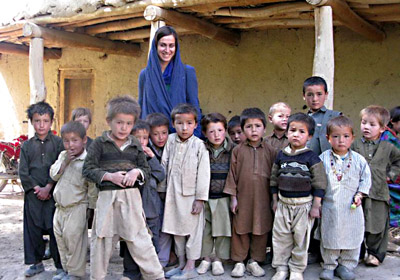

Fotini Christia interviews Afghanistan’s fierce fighters and reveals the potential for a more successful U.S. strategy — and more stability for the Afghani people.

The specter of slaughter of neighbor by neighbor—in the Balkans, Afghanistan, Rwanda, Uganda and elsewhere—can lead us to believe that ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity is a deadly tinderbox, ever vulnerable to sparks, no matter how long groups have lived peacefully side by side.

Fotini Christia, Assistant Professor in the School’s Department of Political Science, challenges that world-weary pessimism.

Through her intrepid field research with Afghanistan warlords, Christia has steadily analyzed the personal, political, and cultural forces that cause a regional or tribal leader to take up arms against a neighboring group, and what allows that same leader—sometimes with mind-boggling rapidity—to put aside the guns and embrace a former enemy.

Christia finds that under certain conditions, even groups sworn to take revenge on one another can overlook longstanding grievances and form new, supportive alliances.

What Can Turn Enemies into Allies?

What is the key? Whatever gives a group a strategic military or economic advantage—even if the action drives them into the arms of their supposed enemies.

“Groups are driven by balance-of-power considerations,” says Christia. “That means that, as relative power changes, so do alliances. Groups then come up with narratives and stories about why they make the alliances they do.”

For example, leaders may rail at a competing group, painting them as implacable or traditional long-time foes. After an alliance is reached, leaders develop a new narrative, now telling stories that portray their former enemies as worthy opponents or long-lost brothers now welcomed into the fold of a new union.

"Fotini understands what was really going on, and what factors were at play in Afghanistan, much better than anybody I’ve seen in the academic world.”

Admiral William Fallon, Former director, U.S. Central Command

Finding A Story

“They can always find a story,” Christia observes. Allying groups may focus on their common language or religious characteristics—those stories tend to be “stickier” or more potent she says. “If they don’t share any of those traits, they move to ideological characteristics (‘We were both jihadis!’) If they don’t share those, they move to economic characteristics (‘We were both nomadic tribes.’) If they can’t find that, they find a shared enemy story.”

Many mainstream media reporters and pundits assume that groups define themselves solely and immutably by ethnicity, culture, religion, or geography. But Christia’s work shows that a host of local power dynamics may be at play establishing group identity in the Near East and elsewhere. Perception of ethnicity, religion and even geography are far more fluid, when political or economic power could be gained by broader definitions. Even a group’s fierce ideology, Christia says, “doesn’t lead to some non-changing equilibrium.”

A native of Greece, Christia studied at Columbia and Harvard before coming to MIT in the fall of 2008. The research for her dissertation, “The Closest of Enemies: Alliance Formation in the Afghan and Bosnian Civil Wars,” has profound implications for U.S. foreign policy in the Near and Middle East. A more open-ended and regionally sensitive approach to confronting enemies and creating allies could prove beneficial both to U.S. interests and long-term stability in Afghanistan, she believes.

Christia’s theories have drawn the support of Admiral William Fallon, who led the U.S. Central Command from March 2007 to March 2008, during which time he directed all U.S. military activities in the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Horn of Africa. Admiral Fallon met Christia while he was the 2008-09 Robert E. Wilhelm Fellow with the School-based Center for International Studies.

“If there’s one thing I learned in the Near and Middle East,” Fallon says, “it’s how rapidly conditions change and how people adapt to them. Fotini understands what was really going on, and what factors were at play in Afghanistan much better than anybody I’ve seen in the academic world.”

Intrigued By Civil War

At age 31, Christia already has extensive experience working in the Middle East and Central Asia; she has written about Afghanistan, Iran, Uzbekistan, the West Bank and Gaza for various publications. Fluent in multiple languages, she speaks English with intensity, and with a slight echo of her native Greek. Asked about the difficulties encountered working in strife-torn regions like Afghanistan, Christia shrugs off the problems with a short laugh, and plunges into a description of what she discovered.

Christia graduated magna cum laude with a joint BA in Economics-Operations Research from Columbia College and a Masters in International Affairs from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. She completed her PhD in Public Policy at Harvard University.

Her interest in civil conflict was sparked at a very young age. Growing up in Greece just as the former Yugoslavia was disintegrating into warring factions, Christia often heard the region’s shifting alliances discussed around her family’s dinner table. (Greece, too, went through its own civil war in the 1940s, but that was a topic talked about only in hushed tones.) In graduate school, Christia became interested in formal study of civil conflicts among multiple players—all-out civil war—an aspect of warfare not as much examined as conflicts between a government and an opposing insurgency.

The Balkan conflict of 1992-1995, when fighting broke out among Bosnia Serbs, Croats and Muslims, seemed to her to be a prime example of conflict in which violence was fierce, and yet sides were fluid. Drawing on her language skills and knowledge of the region, Christia interviewed some 100 people in the Balkans who played key parts in the war; some of them had served prison time for their actions.

Economic incentives can moderate ethnic divisions

While the Bosnia conflict is often cast in terms of three warring ethnic groups—Bosnian Muslims, Serbs and Croats—Muslims sometimes fought against other Muslims even as they were facing violence and forced expulsion from Serb and Croat forces. Christia focused on the intra-Muslim civil war in northwestern Bosnia, which resulted in almost twice the number of battleground deaths as in the Serb-Muslim conflict in that area

Analyzing the role of local elites, Christia sought to explain the trade-off between ethnicity and economic payoffs. She concluded that while people support the warring side most likely to provide for their survival and wellbeing (which is usually their own ethnic group), they also respond to local economic incentives provided by charismatic leadership.

“Economic payoffs can push people past the threshold where ethnicity matters—so much so that people are willing to fight against members of their own ethnic group,” writes Christia in “Following the Money: Muslim versus Muslim in Bosnia’s Civil War,” (Comparative Politics, July 2008).

"Christia's research has profound implications for U.S. foreign policy in the Near and Middle East...and could prove beneficial both to U.S. interests and long-term stability."

Into the Labyrinth

Wanting to press deeper into the labyrinth of ethnic conflict, Christia turned next to the even more complicated series of alliances made and broken during the 1990s civil war in Afghanistan. She was intrigued by the ever-changing relationships among the Pashtun, Tajiks, Hazara, Uzbeks and other ethic and regional groups who fought each other in a dizzying carousel of shifting alliances following the Soviet troop withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989 and the collapse of the communist government in 1992.

For a decade, these groups changed sides constantly, in attempts to gain the upper hand. Under ever-shifting battle cries, the local warlords—powerful regional commanders who provided economic incentives and local governance—led their forces into clashes with other warlords. For example, Uzbek leader Abdul Rashid Dostum first joined forces with Northern Alliance leader Ahmed Shah Massoud, then turned against him. Abdul Ali Mazari, an ethnic Hazara leader, fought against, and then allied with, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the leading Pashtun jihadi leader. Hekmatyar himself fought against and allied with nearly every group in the country. These names and relationships roll easily off of Christia’s tongue, even as a listener struggles to keep track of who fought whom—and when, and why.

Christia believes that more than the fighting itself, this “flipping”—the tactic of changing forces—decided major outcomes. Call it defection or call it realignment, flipping is the Afghan way of war, she concludes.

In 1998 the Taliban—a primarily Pashtun, conservative group with support from Pakistan—captured more than 80 percent of Afghanistan, becoming the de facto rulers of Afghanistan. The Taliban were ejected after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when American forces—who found common cause with Taliban opposition groups—invaded Afghanistan to destroy al Qaeda forces, led by Osama bin Laden, that were allied with the Taliban. With American support, the Taliban were decimated and the current government was installed.

“They would say to me, ‘I’m sorry I’m too busy’ and I would say, ‘That’s too bad because So-And-So agreed to talk to me and I am sorry your version won’t make it into the book’ and they would say, ‘No, my version has to be there. We will make it happen and we will meet again if we have to.’”

Fotini Christia

on the process of interviewing Afghani warlords

To understand why Afghanistan alliances were made and broken, Christia decided to not only go to Afghanistan but to learn Farsi (and the regional dialect called Dari), so that she could communicate with local warlords directly, without relying on interpretation. She took Farsi classes at Harvard, where she was asked to memorize Iranian epic poems, an exercise she balked at, feeling that she needed to concentrate on learning contemporary expressions. She also spent summers studying Farsi at the University of Tehran; in her MIT office she proudly displays her prized University of Tehran I.D., with its photo of her in her headscarf.

In 2004, she made her first trip to Afghanistan. Paying $500 a month for a windowless room in a United Nations guesthouse in Kabul on a road called “Garbage Street,” she set about making contact with regional tribal leaders.

Making "cold calls" to former Commanders

“People from the U.N. thought I was crazy,” she recalls. Undeterred, Christia pressed forward with her “cold calls,” first targeting the commanders who had played major roles during the civil war, but who had fallen out of favor more recently, and were, she speculated, probably craving some attention. Explaining that she was an academic researcher working on a book, she used charm, guile and persistence to set up meetings and follow-up visits. She soon discovered why these men were warlords: they were intense, charismatic, canny—and narcissistic.

Leaders who were now part of the Afghanistan government were at first elusive to pin down. “They would say to me, ‘I’m sorry I’m too busy’ and I would say, ‘That’s too bad because So-And-So agreed to talk to me and I am sorry your version won’t make it into the book’ and they would say, ‘No, my version has to be there. We will make it happen and we will meet again if we have to.’ ”

Once meeting was set up, she usually spent hours in conversation. As the local saying goes, “You need to have at least three cups of tea before they start telling you the real stuff.” So over numerous cups of the local brew, Christia would ask specific questions as part of a formal interview, and then gradually steer the conversation into a more freewheeling discussion.

“All of them were very gracious during the interviews and you see why they have the followings that they do,” she says. “At the same you also know what they are capable of.”

Tea with Pashtun leader Sayyaf

One of the more intense interviews was with the Pashtun leader Abdul Rasul Sayyaf in July of 2005. Just weeks after Christia had arranged for an interview with him, Human Rights Watch, an independent organization that monitors human rights issues worldwide, released a report linking him with particularly horrific civilian massacres of Hazaras in Kabul during the war.

Uncertain about what to expect, Christia arranged with a local driver to take her to Sayyaf’s fortress-like house on a hill overlooking Paghman, a city west of Kabul. She dressed for the visit carefully, in a long dress and pants and a scarf covering her hair. Secretly, she was grateful that local Islamic protocol, which forbids a man from touching any woman who is not his wife, would preclude a handshake. Just outside the Sayyaf compound, she was met by cars filled with his guards; her car was examined, and then all the vehicles proceeded in a convoy to the house.

Christia believes that more than the fighting itself, what she calls “flipping”—the tactic of changing forces — decides major outcomes in Afghanistan. Flipping is the Afghan way of war, she concludes.

As she walked into Sayyaf’s home, she was met by a man with a long, snowy beard and white skullcap, dressed in traditional tunic and pants. Sayyaf looked to be in his 60s, but his age was hard to determine. A servant set a tray of apricots, pomegranates, grapes and melons before her. Over several cups of tea, she and Sayyaf chatted, as one of his deputies dozed in a corner. She complimented him on his impeccable English. He told her he had intended to go to Georgetown University, in Washington D.C., to pursue a master’s in Islamic law. But when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, he ended up fighting in the jihad instead. To Christia’s relief, the warlord answered her questions willingly.

Sayyaf’s comments were of particular interest to Christia because this former mujahedeen—who had been linked to the Saudis during the Soviet war—had switched alliances numerous times. He was originally an opponent of the Taliban even though his religious and ideological sympathies were similar. While he was linked to the deaths of civilian Hazaras in the Afshar neighborhood of Kabul in 1993, he had later joined forces with Hazaras when he became part of the Northern Alliance. Yet, he had also been implicated (this was never proven) in the death of Taliban foe and Northern Alliance leader Massoud in 2001.

Asking the hard questions

The meeting had one very tense moment. When asked how he, a South Asian, Pashto-speaking Sunni could ally with the Central Asian, Dari-speaking, Shia Hazaras, Sayyaf explained, “We all are Afghan brothers.”

“That is interesting,” Christia replied. “How is it then that you have been accused of killing thousands of Hazaras?” No sooner had the words left her mouth, she wondered if she had gone too far. But Sayyaf remained composed, his dark eyes revealing no emotion. There was no ethnic targeting in 1993, he said; rather the fighting was all in the context of a war.

“There is no doubt these people have blood on their hands but they are also very charismatic,” Christia explains. “Sayyaf is extremely intelligent. People look up to him; he has a following. At the same time he can look at you with a composed face and say, ‘This is war. These things happen.’”

Narrative Twists and Turns

More interestingly for Christia’s research was how for each strategic twist and turn, Sayyaf—like other interviewees—would cite a historical or cultural “narrative” to justify why sworn enemies could be friends. For example, when she asked Hazara local leader Haji Mohammad Mohaqeq why Tajiks, Uzbeks and Hazaras formed an alliance in March of 1992, he responded, “We are all people of the north,” as if the Northern Alliance was based merely on geography.

When she asked the Pashtun leader, Wahidullah Sabaun, how the communist-hating Pashtun could ally with the Uzbek leader Dostum, who had been closely associated with the Russians, he replied, “We were fighting against the Tajiks’ monopoly of power.”

The Power of Poetry

Being a Western woman, strangely enough, turned out to be an advantage in these conversations. “It was hard with some individuals who tended to be very religious, but overall, it was actually a plus,” Christia says. “They saw me as someone who was non-threatening and therefore they wanted to talk to me. I could speak their language. I was treated as a third sex. I couldn’t be just female because I was too knowledgeable.”

Another benefit was her Greek background. The Tajiks, she recalled, “were excited that I was Greek because they had these glorious stories about Alexander the Great,” who conquered the region circa 320 B.C. “You’d think that because they were conquered they’d be semi-pissed off, but they were like, ‘You’re a sister because you’re a descendant of Alexander.’”

She also impressed her Tajik interviewees with her recitation of Iranian epic poems. “It was a great icebreaker,” she recalled, “and I had to come back and tell my Harvard professor that the ancient poems could have tremendous contemporary relevance!”

She would visit Afghanistan in 2004, 2005, 2007 and 2009, talking to some 50 warlords. However, she was able to connect with only a few Taliban leaders, who were then expelled or in hiding. So she also drew on memos, memoirs, fatwas, alliance agreements and transcripts of interviews with prisoners at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp for her dissertation. Ultimately she characterizes her conclusions as “counterintuitive.”

Ethnic and cultural identity does not determine alliances, yet such identity is invoked and called on in the narratives that are developed to justify decisions on alliances.

How to Handle the Taliban

In the ever-shifting mosaic of Near East and Middle East politics, ignoring the possibility of turning enemies into friends is self-defeating, Christia argues. Indeed, one of the most intriguing observations in her research is that elements of the Taliban—typically portrayed as an implacable block of Islamic fanatics—could find reason to “flip” and cooperate with the United States.

“Few factors have motivated individual Afghan commanders in their thirty years war more than the desire to end up on the winning side,” Christia writes in “Flipping the Taliban: How to win in Afghanistan,” an article co-written with Michael Semple and published in the July–August 2009 issue of Foreign Affairs. “In doing so, they have not declared their loyalty to a new cause or different tribe; they have argued that circumstances, such as a shift in the balance of power, demanded a strategic realignment.”

“We need to take advantage of the fissures within the Taliban, and flip the moderate elements — and there are many.”

Fotini Christia

Associate Professor, MIT Department of Political Science

This is a key point for U.S. forces in determining the best policy for supporting moderate elements in Afghanistan. In the past two years, the Taliban has re-emerged as a potent force, pushing the Afghanistan government out of huge swaths of the countryside. However, the Taliban today is different from the Taliban of the 1990s, when it enjoyed substantial support from Pakistan. Before 2001, the Taliban was perhaps the most powerful group in Afghanistan; thus it didn’t change sides, as did the others. Rather, the other sides formed alliances as a counterweight to the Taliban (although when one of those groups seemed to gain the upper hand, the other groups realigned to improve their positions.)

Currently the Taliban is composed of three major groups and numerous subgroups; its numbers are uncertain; estimates range from as many as 15,000 people, to as few as 5,000. “We need to take advantage of the fissure and splits within the Taliban and flip the ones that are moderate elements—and there are many,” Christia says. To do this, the United States must retain a strong military presence in Afghanistan and to, in effect “squeeze” the Taliban.

"The Tajiks were excited that I was a Greek because they have these glorious stories about Alexander the Great...They were like, 'You're a sister because you're a descendant of Alexander.'"

“You can’t convince people that they should join you if they are winning. They have to feel like they’re not going to be winning or there is not a stake for them at the end,” she says. Such a show of force, however, should be accompanied by a committed effort to persuade large groups of Taliban fighters to put down their arms. The trick is distinguishing the “good” Taliban from the “bad” Taliban, she says. There are irreconcilable elements, perhaps a third of the Taliban. The rest, however, can be flipped.

Unfortunately, the Bush-Cheney administration did not take advantage of the Afghan way of war. Former Taliban leaders were shipped to detention in the Guantanamo Bay prison, even after they sought government protection. “The message from Washington and its Afghan allies could hardly have been clearer: hold out an olive branch and you will go straight to jail,” Christia says.

Reason to hope for peace

Fallon says that Christia’s research has captured the essence of the challenges he faced in 2007 to 2008 while he was responsible for U.S. operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. “People back here (in Washington D.C.), remote from Iraq and Afghanistan, had their minds made up about how things were, based on a snippet or sound bite of a media report, which maybe could have been accurate at certain time and place,” he says. “But there are many complexities at play all the time.”

This very complexity gives Christia hope that, under the right conditions, ethnic groups can co-exist peacefully. “Many observers have this notion that there are intractable differences—that Sunni and Shia, for example, will always be enemies—but in fact, we see that groups in war redefine themselves to justify their alliance choices,” she says.

“My argument is that these groups are motivated by concerns of power. Shared identity is not going to determine whether they are going to be (friends) with one another or fight against one another. In the civil war context, they can be enemies one day and friends another.” ∎

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand, SHASS Communications Director

Writer: Stephanie Schorow