Continuum | Michael Cuthbert

Equally at home in history and in leading technology,

Cuthbert works along a continuum of time, at once

showing MIT students the power of historical context

and the illuminations of new technology.

ON ANY GIVEN DAY, Michael Cuthbert might be found immersed in the Renaissance, or innovating with computer algorithms in his music21 lab. An Associate Professor in the School's Music section, Cuthbert researches along a continuum of time, finding resonance between the past and the arriving future. He has worked extensively on computer-aided musical analysis, on fourteenth-century music, and on the music of the past forty years. Cuthbert recently corresponded with us from Florence, where he is a 2009-2010 Fellow at Villa I Tatti, Harvard University's Center for Renaissance Studies.

Letter from Florence

This year Cuthbert is walking and reading in the Villa I Tatti's tranquil gardens, and sharing Tuscan meals with fellow scholars, all experts in Renaissance art, dance, history, or culture. The villa is an ideal setting for scholars of the period to study, surrounded by Renaissance materials and forms.

Cuthbert is devoting his I Tatti year to writing a book on Italian sacred music of the seventy year period between the arrival of the Black Death in Italy (1348) and the end of the Great Papal Schism (1417). His work on the music of this time was also furthered by a Rome Prize in Medieval Studies, which gave Cuthbert the chance to study musical sources through close examination of damaged, but digitally enhanced music fragments.

gardens of Villa I Tatti (photograph courtesy of Giovanni Trambusti)

“Now I want to put that music in the context of daily life in fourteenth and early fifteenth century Italy," he writes from his Florentine study. "I know what music a monk in Venice might have copied or the songs a group of young women in Florence might have sung. But what did that monk eat for dinner? What dances accompanied the women’s songs? These are the details that give life to a musical period."

The I Tatti fellowship is also perfect for practicing his Italian and German, weak points, Cuthbert says modestly, who grew up as a “Navy brat” in San Diego. His strong points in music and math developed through playing the clarinet and, later, composing on an old Commodore 64. His mother, a native of Okinawa, and his American father weren’t particularly musical, he says. The family owned a single LP of classical music—Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony—and lots of country music, which Cuthbert still enjoys. Cuthbert’s resourcefulness and “really amazing teachers in schools with few resources” ignited and sustained his musical and academic journeys.

Cuthbert immerses himself in 14th century music history

because “some of the most beautiful, strange, and

undiscovered music is there." Music history, he says,

also offers MIT undergraduates the chance to learn

independent research skills that will serve them well

in their lives as scientists and engineers.

Knowledge from physical presence

Like Ellen Harris, who enjoyed poring over “Messiah” composer G. F. Handel’s investment ledgers while sitting in a Bank of England basement vault, Cuthbert finds adventure, excitement, and significance in the tactile experience of physically holding 600-year-old manuscripts.

“I travel to see the originals because there is something in them that can only be discovered in person. I work on pages of sheepskin where the music has been washed or scraped off so the parchment could be reused. I can hold the page so the light reflects off it in just the right way for me to see its almost-invisible notation,” he writes. “You can’t do that with a reproduction.”

As for the Black Death project, Cuthbert has found that the music and art of the time were not as somber as you might expect from a time when millions were dying of the rat-borne pox. “When you look at the literature and musical poetry," he writes, "it appears the disease that people most feared catching was lovesickness."

Cuthbert immerses himself in 14th century music history, because “some of the most beautiful, strange, and undiscovered music is there.” He encourages his MIT students to study the period, too. “Music history, like the School’s other humanities courses, offers undergraduates the chance to learn independent research skills—identifying a new problem, finding a methodology to solve it, writing up their results—that they will need for future work in science or other fields.”

New tools for ancient sounds

Cuthbert’s other great love is futuristic, computer-aided musicology. Some would proudly call it "geek" musicology. For this work, he swims in an algorithmic sea, honing programming techniques to conduct musical analysis. This innovative research has been supported with two $100,000 grants for Digital Humanities, awarded by the Seaver Institute in 2009 and 2010.

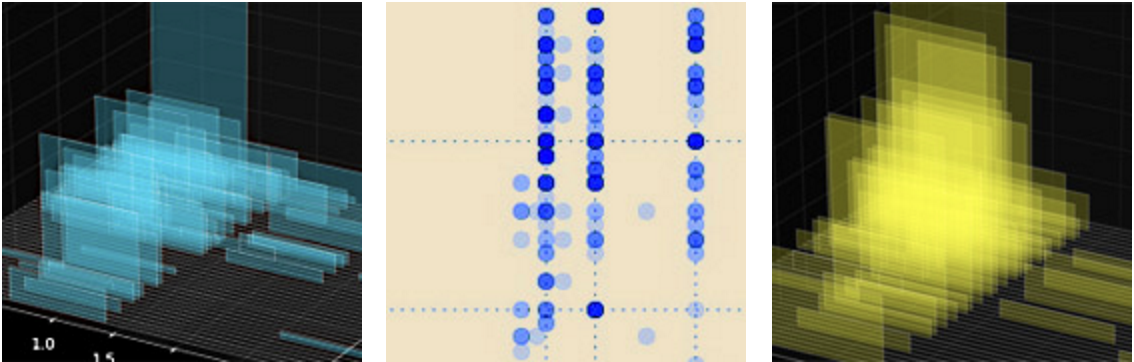

The grants primarily fund music21, Cuthbert’s MIT research lab and a three-year project to create new tools for music research and analysis. By combining tools of musicology and of computer programming, Cuthbert’s music21 project will equip computers with a basic understanding of music theory, making it possible for researchers to explore such questions as: How did variations in Gregorian chant spread geographically and over the centuries? What makes French music French? Pilot applications have already helped Cuthbert to find matches for extremely damaged late-medieval songs and to analyze early 15th-century rules for improvisation with voice or instruments.

music21 is Cuthbert’s MIT research lab and a project that combines

tools of computer programming and musicology to create new tools

for music research and analysis. At MIT, he says, students in every

discipline have profound opportunities to contribute to research in

music and history. Science majors can use chemical analyses of ink

content on medieval manuscripts. Economic models can apply to

musical patronage.

A global arts technology

Consistent with the School’s focus on world citizenship, music21 is a global arts technology. “Ideas that are important for classical music are not universal; they’re European, and we’ve labeled them as such. For the analysis to work, researchers will have to provide the context for their inquiries: The context of Mozart is different from the context of Yoruba drumming. Same thing for pitch: What was considered dissonant for Bach can be wonderfully consonant in Pakistani music,” he says.

In the global world of music, faculty and student scholars need diverse methodologies to excel in innovative research, Cuthbert notes. “At MIT, students in every discipline have profound opportunities for contributing tools or strategies to research in music or history. Science majors can use chemical analyses of ink content on medieval manuscripts. Economic models can apply to musical patronage.”

MIT students have already contributed to music21, says Cuthbert. “One designed a tool that, when given one melody, automatically writes another melody on top of it. Another integrated Google Maps with an interactive timeline and mp3 player so she could hear pieces from particular regions and particular times.”

Cuthbert's engagement with his musicology students encourages depth, historical and global perspectives, and creative innovation, qualities that help his students prepare for their roles as leaders.

Listen | Music Program

State of the Art | Introduction

Cuthbert | Continuum

Makan | Starting with Silence

Tang | Global Drumbeat

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Editor and Design Director: Emily Hiestand

Writer: Sarah Wright

Photographs of Villa I Tatti, courtesy of the photographer Giovanni Trambusti

Villa I Tatti is Harvard University's Center for Renaissance Studies.

Published May 5, 2010