Book Talk: The Hunt for Vulcan

Tom Levenson discusses his new book

For more than fifty years, the world’s top scientists searched for the “missing” planet Vulcan, whose existence was mandated by Isaac Newton’s theories of gravity. Countless hours were spent on the hunt for the elusive orb, and some of the era’s most skilled astronomers even claimed to have found it. There was just one problem: It was never there.

Tom Levenson, MIT Professor and Head of the Graduate Program of Science Writing, will talk about his latest book in conversation with David Kaiser, Germeshausen Professor of the History of Science, Professor of Physics, and Head of the Program in Science, Technology, and Society, on Tuesday, November 3, 2015, at the MIT Museum, 6-7:30pm. The event is free and books for signing are available for purchase in the MIT Museum store.

The Hunt for Vulcan And How Albert Einstein Destroyed a Planet, Discovered Relativity, and Deciphered the Universe tells the story of the search for — and repeated discovery of – a planet that was and wasn’t there. The story of the ambiguous planet Vulcan and provides another reason to celebrate Albert Einstein on the 100th anniversary of the General Theory of Relativity.

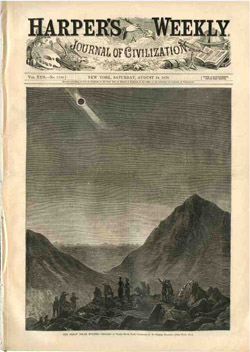

The planet Vulcan itself was born in 1859, when Urbain Jean-Joseph Le Verrier, the greatest mathematical astronomer of his day, announced a calculation that revealed a tiny wobble in Mercury’s orbit. Using Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity – the single most successful idea in the history of science, and by general agreement the climax to the Scientific Revolution — that glitch could only be explained by the gravitational influence of some as yet undiscovered body: a planet, Vulcan.

Almost immediately, an observer reported seeing Vulcan, a discovery that launched twenty years of similar reports, at least a dozen in all, claims made by reputable amateur and professional astronomers alike.

But here’s the catch: the wobble in Mercury’s orbit is real. The best science of the day really allowed only one explanation: Vulcan. And yet, it was never there.

L: Tom Leverson, Professor of Science Writing; Director, MIT Graduate Program in Science Writing; R: David Kaiser, Germeshausen Professor of the History of Science, Professor of Physics, and Head of MIT’s Program in Science, Technology and Society

The problem of Mercury and the missing planet would only be solved in November, 1915. Albert Einstein, working utterly alone within a war torn Berlin, invented his General Theory of Relativity, an utterly new and strange conception of gravity. Einstein’s vision of gravity as warped space and time fully explained why Mercury moves as it does, and thus eliminated the need for an extra planet.

That success — general relativity really is the way the universe organizes itself — transforms Vulcan from a curiosity into a true mystery: why did so many see what wasn’t there? Why did no one until Einstein came along begin to wonder if Newton might actually be wrong?

Levenson and Kaiser will talk about all that: Vulcan’s strange history— and what this mostly forgotten tale from 19th century astronomy tells us about how hard it sometimes is for science and scientists to change their minds.

About

Thomas Levenson is a professor at MIT and head of its science writing program. He is the author of several books, including Einstein in Berlin and Newton and the Counterfeiter: The Unknown Detective Career of the World’s Greatest Scientist. He has also made ten feature-length documentaries (including a two-hour Nova program on Einstein) for which he has won numerous awards.

Suggested Links

The Hunt for Vulcan

And How Albert Einstein Destroyed a Planet, Discovered Relativity, and Deciphered the Universe

Tom Levenson

David Kaiser

Graduate Program in Science Writing

Program in Science, Technology, and Society

MIT Museum