Christine Walley and Chris Boebel on the Exit Zero Project

Transmedia storytelling explores deindustrialization and economic inequality in the U.S.

"Our hope is that, by working across media, we can engage a more diverse audience with these arguments than would have been otherwise possible."

The Exit Zero Project takes its name from the freeway exit number for Southeast Chicago’s former steel mill region, once one of the largest steel-producing regions in the world. It’s also the community in which MIT anthropologist Christine Walley was born and raised. Walley’s father had worked in a steel mill for most of his adult life — until it closed, abruptly, in 1980. The closure left Walley’s father out of work, along with many thousands of other workers and stripped former employees of their retirement funds. Over time, all of Southeast Chicago’s steel mills would close leading to the growing impoverishment of a once middle class region.

Walley and Chris Boebel, filmmaker and Manager of Multimedia Development in the MIT Office of Digital Learning, founded the Exit Zero Project as a transmedia effort to tell the story of the traumatic effect of deindustrialization on Southeast Chicago. The three components of the project — book, documentary film, and in-progress interactive website — use family stories from the once-thriving steel mill communities of Southeast Chicago to consider the enduring impact of the loss of heavy industry and its role in widening class inequalities in the United States. SHASS Communications spoke with Walley and Boebel recently about the Exit Zero project.

Was Exit Zero envisioned as a multimedia project from the very beginning? What did you hope to achieve by adapting the stories and research behind Exit Zero for these different media?

We originally conceived of the Exit Zero book and documentary together as two explorations of the same topic in different media, each capable of conveying different dimensions.

From early on, we knew we wanted to explore the topic of deindustrialization — which we see as strongly related to expanding economic inequality in the United States — through film. When Chris Boebel first visited Southeast Chicago in the 1990s, he was struck as a filmmaker by the highly visual nature of the landscape: massive empty brownfields, landfills, and rusting industrial infrastructure in the midst of lakes and wetlands with the old mill neighborhoods interspersed in between.

The visual material in the film, which includes archival footage, home movies, and verite sequences shot as far back as the early 2000s, offers a different sense of intimacy than the book does, as well as its own unique insights into the transformation of this region. The goal for both the film and book was to avoid the distance that can be produced by an overtly academic style, and to instead use family “stories” to convey the subjective and experiential dimensions of deindustrialization.

It is also worth mentioning that, although stories make up the center, the project is based upon years of ethnographic fieldwork and archival research. It is very much in conversation with the academic literature on deindustrialization, working class studies, and urban ethnography. So the book and film convey analytical arguments as well as personal narratives. Our hope is that, by working across media, we can engage a more diverse audience with these arguments than would have been otherwise possible.

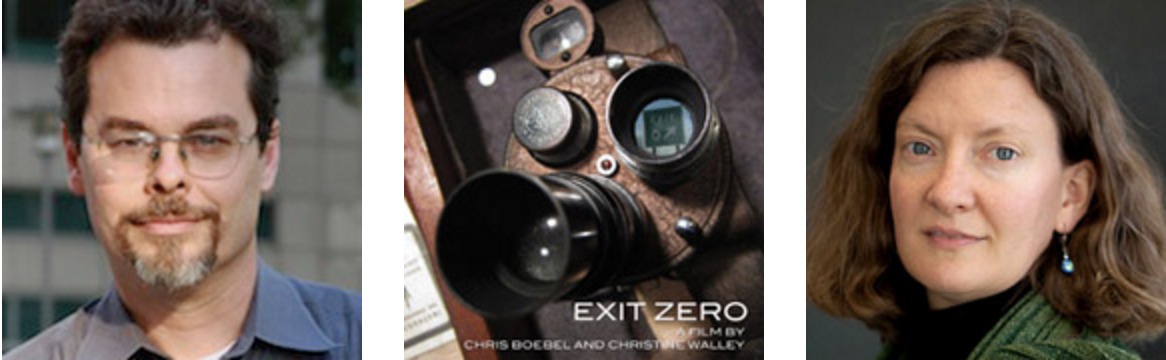

L: Chris Boebel, filmmaker and Manager, Manager of Multimedia Development, MIT Office of Digital Learning; R: Christine Walley, Associate Professor of Anthropology

"It’s now clear that certain categories of people benefited from recent economic transformations, while many others were left behind. The film reflects on these changing national narratives and why those who might consider themselves working class are no longer at their center."

In the film, Christine notes that “the stories we tell, make us who we are.” What does the story of Exit Zero tell about contemporary society? Is it a particularly American story, or does it resonate in other contexts as well?

Southeast Chicago is a place that, historically, took the narrative of the “American Dream” to heart. It was a working class community that had seen rough times from the 19th century up through the 1930s and 1940s. In the post–World War II period, however, with better wages and more job security, more people began to feel as though they had moved into the “middle class.” There was an assumption in this community — as there was in U.S. society more broadly — that an ever-expanding middle class and better standard of living would be the wave of the future.

When the steel mills began shutting down in the 1980s and 1990s, this narrative was radically challenged. Suddenly, people who assumed they had some stability, and who could envision their place in the world, felt like that was no longer the case. In many quarters, industrial jobs began to be seen as the dirty relics of a bygone era, and good riddance, as we moved towards an information-based economy that was supposed to be the key to enhanced prosperity in the future.

Thirty-five years later, no “new economy” future has appeared in Southeast Chicago or in many other formerly industrialized regions. In fact, many areas like Southeast Chicago are still struggling with the toxic legacy of the industrial past: the pollution is there, but the jobs aren’t. On a larger level, it’s now clear that certain categories of people benefited from these economic transformations, while many others were left behind. The film reflects on these changing national narratives and why those who might consider themselves working class are no longer at their center.

Chuck Walley and his mother on their front porch, late 1940s (Photo from the Walley family)

"Thirty-five years later, no 'new economy' future has appeared in Southeast Chicago or in many other formerly industrialized regions. In fact, many areas like Southeast Chicago are still struggling with the toxic legacy of the industrial past: the pollution is there, but the jobs aren’t. "

As an anthropologist and filmmaker, we believe that “stories” are key to how we understand the world. Our analyses — and even the data we use — are very much shaped by the larger narratives we tell. While the “American Dream” narrative says something striking about U.S. history and culture, deindustrialization and expanding inequality certainly aren’t limited to the United States. Parallel trends in a number of other regions have occurred, although national governments might deal with common stresses in different ways—and, in part, we deal with these pressures differently because of the kinds of narratives we tell ourselves about them.

The fact that the current U.S. presidential political campaigns have revolved around these issues—to an extent that initially surprised pundits — is not surprising from the point of view of places like Southeast Chicago. The question is: what is our analysis of why such transformations have happened and what should be done about it? The worry isn’t about “industrial” jobs per se, but about the prospects for good, stable jobs that allow for an expanding middle class to move forward.

The Exit Zero Project also features an interactive website, produced in partnership with the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum. What are your hopes for this online portion of the project?

The Exit Zero book and film were conceptualized together, but the idea for the in-progress website project came later. It emerged in response to encouragement from MIT’s Open Documentary Lab, which has convened a fabulous group of people exploring alternative kinds of documentary work using online formats.

The Southeast Chicago Historical Museum is an all-volunteer Museum located in a single room. It’s stuffed to the rafters with historical materials saved by Southeast Chicago residents, dating from the time the steel industry began collapsing to the present. The materials include photos, home movies, documents, scrapbooks, objects, and oral histories. The goal for the website is to create both an online archive of museum materials and a storytelling site about deindustrialization; we particularly want to emphasize the kinds of stories people tell through the material artifacts they choose to save.

If the Exit Zero book and film use certain family stories as a way to approach deindustrialization, the website project is designed to emphasize the diversity of stories found in Southeast Chicago across the wide range of ethnic and racial groups that have historically called this area “home.” Although people often associate “deindustrialization” with its impact upon the white working class, its effects have, of course, been far broader. In Southeast Chicago, we’ve seen even more serious impacts for the large number of Mexican-Americans and African-Americans who lived in the area or worked in its steel mills. Writing academic books and making films generally entail linear forms of storytelling, and we’re excited by the possibilities this online documentary work creates for a multilinear approach that can underscore this diversity.

Suggested links

Exit Zero Project

Preview of "Exit Zero"

Chris Beobel

MIT-SHASS Anthropology

MIT Open Documentary Lab

Archive: Hard times in Chicago

Archive: Walley receives James Best Book Award for Exit Zero

About the Book + Reviews | University of Chicago Press

Archive: MIT Report identifies keys to new American innovation

Archive: Suzanne Berger on converting innovation into growth

Story prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Emily Hiestand, Editorial and Design Director

Daniel Evans Pritchard, Writer, Senior Communications Associate