Spotlight | Humanities

Class on digital humanities premieres with tech-savvy approaches

"Because this class took place at MIT, many students were adept at computer programming, so they were able not only to conceptualize what kinds of tools might prove useful to their clients — they were also able to build them."

Among the Humanities endeavors at MIT are a range of projects in the digital humanities — a field of research, teaching, and creation that couples the disciplines of the humanities with computational approaches. Digital humanities projects often use methodologies and techniques such as web-based media, digital archiving, data mining, geo-spatial analysis, crowdsourcing, data visualization, and simulation.

At MIT, digital humanities practioners use digital tools and “big data” to investigate research questions (many that can only be asked with the speed of the new tools) while also presenting scholarship through, and within, new media forms.

This story looks at how MIT humanities faculty are engaging students with the potentials of digital humanities for research and innovations.

Project-based class in digital humanities

First offered in the Spring 2013 term, and taught by Professor James Paradis and Principal Research Associate Kurt Fendt, both of Comparative Media Studies/Writing, "Digital Humanities: Topics, Techniques, and Technologies" (CMS.633), gave MIT students the chance to pair technical know-how with real-world humanities projects — such as designing innovations for the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston (ICA), and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Students were introduced to key digital humanities concepts, including data representation, digital archives, user interaction, and information visualization, then given opportunities to apply these to a variety of challenges. In addition to devsing potential solutions for the two Boston museums, students also took on the MIT-based Comédie Française Registers Project and the Edgerton Digital Collections — in both cases grappling with a common digital humanities problem: how to make use of vast amounts of data.

“Digital humanities is a fresh approach," Paradis says, "It's thinking about how new forms of representation can be used to solve problems. It’s applied humanities.”

Putting ideas into action

Because this class took place at MIT, many students were adept at computer programming, so they were able not only to conceptualize what kinds of tools might prove useful to their clients — they were also able to build them.

“Many other schools who are prominent in the digital humanities offer more traditional humanities courses than we do,” Fendt says. “They simply don’t have students with the building experience that MIT students have.”

MIT student teams immediately put their ideas into action: those working for the Comédie Française Registers Project and the Edgerton Digital Collections developed tools to make it easier for scholars to mine rich new sources of data; those working for the museums found new ways to use technology to enhance the visitor experience. “Students could really examine real-world problems and experience what these institutions are dealing with,” Fendt says.

Information tools for museum visitors

For the ICA, the challenge was how to make better use of its large lobby. Students responded by designing what they called the “The i SEE a Portal,” employing a graphical user interface and a Python game module to engage visitors in a touch-screen display intended to be installed in the lobby. “It’s dynamically rearrangeable, so it’s a playful, interactive service,” says Dmitri Megretski, ’13, an electrical engineering and computer science major.

For the Gardner, students were challenged to design media for the hallways connecting the museum's original building— which has a no-mobile policy— to the Gardner's new wing, a space that welcomes new technologies and interactions. Students developed a digital “guestbook” that would also serve as an interactive artwork. Employing data visualization techniques they had learned in class, students proposed different ways to display visitors’ tweets about the museum. In one, the letters of each message appeared to fly off the page, changing in real time as new messages came in. In another, the tweets appeared as a succession of word clouds. “People want to see what they wrote, see their mark,” says Birkan Uzun, ’15, an electrical engineering and computer science major.

Tools for asking new questions

Visualizing data was also a central concern for students working on the Edgerton Digital Collections, an effort to provide the first online access to the research notebooks of MIT pioneer Harold “Doc” Edgerton (1903-1990), the creator of such iconic photographs as those of a bullet going through an apple.

To enable scholars to glean information quickly, the students developed a timeline spotlighting Edgerton’s interactions as referenced in the original source materials. “You can see what kind of experiments Doc Edgerton was working on and who he was working with,” says Chau Vu, ’14, a biology major, noting that the tool also allows users to click through to view the original notebook pages.

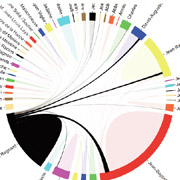

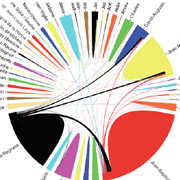

Facilitating historical research was likewise the focus of the Comédie Française team, which developed a visual search engine to assist the ongoing effort to make the complete registers of the Comédie Française theater troupe (1680-1800) accessible online. The tool makes it possible to search the theater’s extensive records (which until 2007 could only be seen in Paris) and filter results by such categories as date, genre, title, and playwright and represent them through dynamic visualizations.

Like many projects in the digital humanities, this one allows scholars to ask new questions about the material, Fendt says. “The Comédie Française usually performed two plays a night, a comedy and a tragedy. So, one question is, how did they decide on those pairings? Such questions cannot be easily answered by poring over handwritten documents one by one, but tools like this can help us gain new insights."

All these exploratory projects demonstrate the breadth of projects being undertaken by those involved in digital humanities. Both Fendt and Paradis say they look forward to seeing what direction the class will take next term, when a new set of students will address fresh challenges.

“This was our first run — and we have big hopes for this course,” Paradis says.

Story prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Editorial and Design Director: Emily Hiestand

Senior Writer: Kathryn O’Neill