Howe documents native people’s initiative in their own anthropology

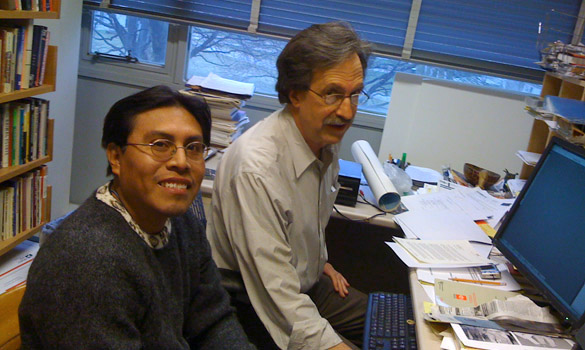

Bernal Castillo, a Kuna and anthropologist, meets with Howe at MIT.

In Chiefs, Scribes, and Ethnographers, James Howe, Professor of Anthropology, illuminates the dialogue at the heart of ethnography, and charts the Kuna's role in their own ethnography—a position that puts them at the forefront of anthropology's ongoing shift from an observational to a collaborative model.

Agents and Subjects

When Swedish anthropologist Erland Nordenskiöld went to study the Kuna people of Panama in 1927, the Kuna were well prepared. Their leader, Nele Kantule, essentially handed Nordenskiöld a record of his people’s customs, beliefs, and history.

“Anthropology of the Kuna was started by the Kuna. And they continue to do it,” said Professor of Anthropology James Howe, who presents a full-length examination of the relationship between the Kuna and their own enthnography in his new book, Chiefs, Scribes, & Enthnographers: Kuna Culture from Inside and Out, (November 2009, University of Texas Press).

Not only did Kantule present Nordenskiöld with texts written in Spanish and English by his secretaries, taken down from Nele's dictation in the unwritten Kuna language, he later sent the secretary, Rubén Pérez Kantule, to Sweden to provide Nordenskiöld with additional information (an extraordinary journey for a 24-year-old Kuna youth). The resulting volume, An Historical and Ethnological Survey of the Cuna Indians, remains a critical resource for Kuna researchers today.

“It’s a very confusing book, but as public relations it was fabulous,” said Howe, noting that the work showed the Kuna to be intellectuals with a rich and complex culture, countering the stereotypes of the day.

Detail, sketch of Kuna scribe Rubén Pérez Kantule meeting with reporters in Sweden 1931

Dialogues and Collaborations

Exploring the Kuna’s history “as agents as well as subjects of ethnography” was an idea that Howe said emerged not only from his 40-year study of the Kuna, but also from his exposure to the great changes under way in the field of anthropology. Beginning in earnest in the 1980s, researchers began to abandon old assumptions and methods,

MIT's Michael Fischer, Professor of Anthropology and Science Technology Studies, is a leading figure in this transition, which is now well underway. One question that has frequently emerged during the shift is: what happens to a culture when anthropologists enter the picture? In considering this, Howe came to recognize how much the Kuna have capitalized on the interest shown in them by outsiders.

“Lots and lots and lots of people study the Kuna," he said. “I realized a lot of this was managed by them; there was kind of a plan there.”

Increasingly, anthropology researchers are acknowledging the dialogues between researchers and subjects, on which ethnography depends, and finding ways to make the process truly collaborative.

For example, Howe writes, “When Nele and his secretaries produced their own censuses, maps and gazeteers, it was precisely because they did recognize such documents as aspects of state power, which they wished to appropriate for themselves. Even after giving up on the dream of complete independence a year or two before Pérez’s trip to Sweden, Kuna leaders were still eager to assert their autonomy, in this case through self-documentation. Thinking like a state, they claimed territory and population by recording them.”

The Kuna are highly organized politically, with a complicated hierarchy of officials and a wealth of democratically-run meetings, Howe said. “Although few Kuna write their own language, they use written Spanish in a great many ways, including their own research, to deal with the outside world,” he added.

“Lots and lots of Kuna do research. All of us outsiders writing about the Kuna—we’re part of their project.”

— James Howe, Professor of Anthropology

Kuna Anthropologists

“Lots and lots of Kuna do research,” said Howe, noting he recently invited one Kuna anthropologist, Bernal Castillo, to speak to students in his new course, Monitoring the Rights of Native Peoples (see story). “All of us outsiders writing about the Kuna—we’re part of their project.

Notably, as the Kuna have gained experience and training in enthnography, they’ve also gained more equal footing with their foreign collaborators—a fact that reflects how much anthropology has changed. As Howe writes, “Latin, Kuna, European, and North American colleagues now communicate and cooperate in a way unknown years ago.”

Related Story: Monitoring Human Rights

See related story on one of Howe's former

anthropology graduate classes, which provided

assistance to the UN's human rights review in Panama.

Story by SHASS Communications

Editorial Team: Kathryn O'Neill and Emily Hiestand

Photographs: top: Bernal Castillo, professional anthropologist and Kuna, meets with James Howe, MIT Professor of Anthropology (photo by Professor of Anthropology Susan Silbey); middle: details from the cartoon sketch of the Kuna scribe, Rubén Pérez Kantule, meeting with reporters in Sweden, 1931; National march in Panama City, 2009, in support of indigenous peoples' resistance to encroachments and oppression; bottom: Kuna woman on the San Blas Island, Panama