2018 JANUARY SCHOLARS IN FRANCE PROGRAM

Outstanding MIT students of French explore "Paris et la rue."

With Professor Bruno Perreau, students discover behind-the-scenes, working Paris.

The MIT January Scholars in Paris, 2018

“We all romanticize the culture of Paris, and it’s fine to do that. But we also need to add different layers and rethink the connection between myth and reality.”

— Bruno Perreau, Cynthia L. Reed Professor and Associate Professor of French Studies

Think of Paris, and images materialize of sublime art and cosmopolitan sophistication. “We all romanticize the culture, and it’s fine to do that,” says Bruno Perreau, Cynthia L. Reed Professor, and Associate Professor of French Studies. “But we also need to add different layers and rethink the connection between myth and reality,” he says.

In search of this connection, Perreau brought seven students to Paris for the annual January Scholars in France program, offered during MIT’s independent activities period. Chosen through a competitive process, the January Scholars students are among the best in MIT's French studies and language program, and spoke exclusivley in French during their stay in Paris. For their travels, the students receive airfare, lodging in a youth hostel, transportation and meals, courtesy of the French Initiatives Endowment Fund.

Led by expert local guides, the group pursued a theme, “Paris et la rue” (Paris and the street), which took them beyond the usual tourist spots and into lesser-known residential and business neighborhoods. During lengthy walking tours, they peeled back layers of history, learned about city planning past and present, and glimpsed behind-the-scenes views of workaday, contemporary Paris. It was an itinerary that encouraged students “to encounter aspects of Parisian life they couldn’t have imagined,” says Perreau.

Sign in a shop in the Goutte D'Or district

Led by expert local guides, the group went into lesser-known residential and business neighborhoods, peeled back layers of history, and glimpsed behind-the-scenes views of workaday Paris.

Another side of Paris

“We got to learn about things like the design process behind the trash cans and the type of barricades built by revolting Parisians from the 17th straight through to the 20th century,” recounts Anelise Newman, a junior majoring in electrical engineering and computer science.

“We saw parts of the city, like the business sector and the atelier and works of Raymond Moretti … and most importantly, we got to interact with Parisians not as tourists, but as students who were genuinely interested in learning the culture and mastering the language,” said Newman who also wrote about the experience for the Admissions blog.

Unexpected episodes enlivened and enriched their daily tours. In a visit to the 13th arrondissement, which began in the 19th century as a factory district and is now home to public housing and a vibrant Asian population, the group took in the many giant murals plastered on the sides of buildings.

Mural by Shepard Fairey, a gift to France after the 2015 attacks

In the 13th district, the students discovered the mural pictured above, "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité." Designed by the artist Shepard Fairey, it was offered to the city of Paris after the attacks of 2015.

Visit the The January Scholars Daily Blog for more photographs

“We triggered reactions from locals, who argued with us about their favorite or most hated pieces of public art,” recalls Perreau. “Students were surprised about how attached people were to their personal visions of the city.”

At La Defense, a sprawling business district dotted by high-rises with a subterranean infrastructure for highways, parking and the Metro, the group found unexpected adventure. The city’s chief archivist and a security detail opened a series of locked doors, and descending a stairway with flashlights, revealed a hidden area.

“We were taken underground to see the atelier and works of Raymond Moretti, a sculptor who passed away thirteen years ago,” says Rebecca Grekin, a chemical engineering major. “We felt so privileged to be invited into a place that was normally off limits.”

Perreau, who likened the concealed cavern to “a cathedral or grotto,” was astonished to find himself face to face with a gigantic sculpture nicknamed “the monster” because of the roar from nearby subway trains.

“We had this feeling of being explorers,” he says. “I saw another side of Paris that had been concealed from me, even after having lived there for years.”

At the Palais Garnier with Germain Louvet, a star dancer (danseur étoile) of the Opera de Paris

“I grew up dancing in Accra, Ghana and was obsessed by the Paris ballet. So first I couldn’t believe I was standing backstage with the étoile (star), and later, I was literally speechless when we went out to a café for drinks with him, and heard about his life”

— Sefa Yakpo ’18, management science and French

Pulling back the curtain

Even at some of the more glittery Parisian venues, MIT travelers were able to pull back the curtain and gain unusual perspectives. During a private tour of the Palais Garnier, home to the Paris Opera Ballet, the troupe’s star dancer, Germain Louvet, showed them spaces normally inaccessible to the public: a fake ceiling behind which gentleman from high society once chose dancers with whom to consort, and in the basement, a tank full of water intended in the 19th century to douse fires, but now full of koi fish.

“I grew up dancing in Accra, Ghana and was obsessed by the Paris ballet,” says Sefa Yakpo, a senior double majoring in management science and French. “So first I couldn’t believe I was standing backstage with the etoile (star), and later, I was literally speechless when we went out to a café with him, and learned about his life,” she says.

To top off this prized experience, the group attended a performance the following night of the ballet Don Quichotte at the Bastille Opera, where they witnessed a once-in-a lifetime crowning of a female star dancer.

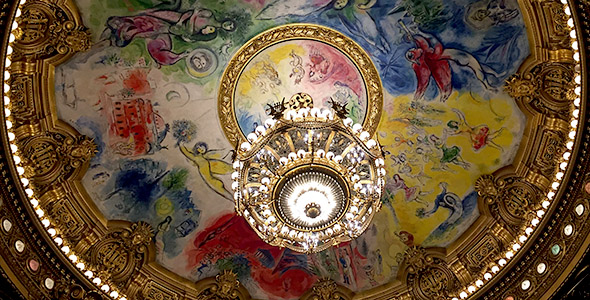

Ceiling painting by Marc Chagall, Great Hall in the Palais Garnier, home of the Paris Opera

“Music, dance, art — things that touch us — are like magic, and Paris reminded me of the importance of that.”

Yakpo, who had worked in Paris the previous summer for a consultant firm, felt as if she was seeing the city for the first time. “I walked on very familiar streets, but peeling off layers of history and understanding the politics and culture of these places showed me how a city can have many different faces,” she says.

One of Perreau’s goals was to “shift students’ perceptions of Paris and France, to build new understanding” while having fun together and enjoying the many riches the city has to offer. “There is something about pleasure at the heart of the program,” he says.

Perreau may have succeeded in ways he didn’t anticipate. Grekin returned to Boston determined to continue the French experience. “I am going to keep practicing the language with a friend I made on the trip, and start going to the Boston Symphony Orchestra,” she says. Safpo found the Paris sojourn a balm for the soul.

“At MIT, where at times facts and solving problems make life seem clinical, you can forget to embrace something just because it’s beautiful,” she says. “Music, dance, art — things that touch us — are like magic, and Paris reminded me of the importance of that.”

Suggested links

January Scholars in France

More photographs and reports on The Daily Blog: 2018 January Scholars in France

Admissions Blog post on January in Paris

MIT Global Studies and Languages

Bruno Perreau's website

Story prepared by SHASS Communications

SHASS Editorial and Design Director: Emily Hiestand

Writer: Leda Zimmerman

All photos by Professor Bruno Perreau

Students in top photograph, L to R:

David Dellal, Mechanical Engineering '18; Anelise Newman, EECS '18; Shannon Miller, Mechanical Engineering '18; Sefa Yakpo, Management '18; Kaymie Shiozawa, Mechanical Engineering '19; Rebecca Grekin, Chemical Engineering '19; Melissa Meloche, Mechanical Engineering '20

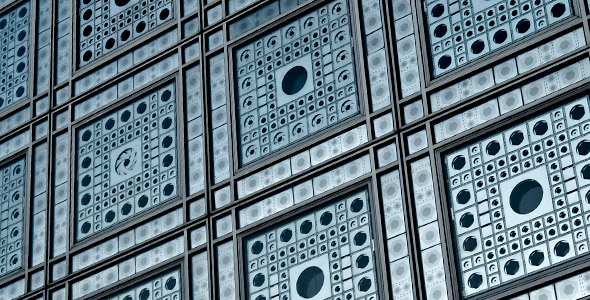

The south facade of l'Institute du Monde Arabe, designed by Jean Nouvel is a grid of 30,000 photosensitive diaphragms (like camera lenses) that modulate light on the interior of the building. The design is at once high-tech, and a reference to the mashrabiyya — an oriel window covered with lattice work used in traditional Middle Eastern architecture for both privacy and sun protection.