Solving Climate | Humanistic Perspectives from MIT

Two-Eyed Seeing

Interview with Patricia Saulis, MLK Visiting Scholar 2020-2021

Patricia Saulis, MLK Visiting Scholar, 2020-2021

"Two-eyed seeing is the practice of applying more than the Western way of knowing to climate issues — allowing for another vision, another sight to be used to see what is happening and to address the impacts...Two-eyed seeing opens the door to meaningful collaboration and learning that has not happened before."

— Patricia Saulis, Executive Director, Maliseet Nation Conservation Council

Full Series Solving Climate | Humanistic Perspectives from MIT

Also See Fast Forward: MIT's Climate Action Plan for the Decade

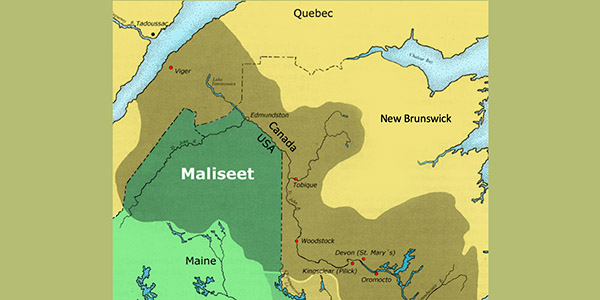

Patricia Saulis is executive director of the Maliseet Nation Conservation Council and a member of the Maliseet tribe of Indigenous People, whose lands lie along the Wolustoq/Saint John River watershed on both sides of the US and Canadian border. She is an MLK Visiting Scholar for 2020-2021 at MIT, where she is collaborating on teaching with Professor James Paradis from Comparative Media Studies/Writing and working more broadly to promote the understanding of Indigenous Peoples and create a more inclusive campus. MIT SHASS Communications spoke with her for our ongoing Solving Climate series.

____

Q: How can insights and perspectives from Indigenous Peoples help address global climate change and its ecological and social impacts?

Indigenous Nations and communities have been in crisis since colonial and racial forces of oppression were brought to bear on our communities. Now, our communities are being impacted by another crisis not of our own creation: climate change. Fortunately, our Indigenous ways of knowing, knowledge systems, cultural paradigms, linguistic complexity, and ancestral practices have equipped us to understand sudden and rapid shifts in the environment. For hundreds of years now, our Elders and wisdom keepers have been saying the same thing: stop exploiting.

Their teachings make it clear that if you take more than what you need, you will end up with a level of depletion that is damaging far beyond what you can understand and forecast. Indigenous Peoples collectively carry ancestral teachings that can provide guidance in making better choices for the planet that will not harm you or those you love. As humans, we are but one species out of more than 8 million in this world. It is imperative that we become more responsible with our habitat.

Indigenous Peoples, Nations, communities are also uniquely positioned to address the many effects of the emerging climate crisis, including the loss of biodiversity — the ecological devastation to species — and the psychological trauma created by sudden change. As a global population, Indigenous Nations and communities live across the planet, each with specific knowledge related to their local ecosystem, and are thereby an integral force for addressing climate change.

Video: Presentation by Patricia Saulis on “Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science: Two-Eyed Seeing"; recorded as part of the MIT Comparative Media Studies colloquium series, 5 November 2020

Research has shown that linguistic diversity and biodiversity are positively correlated, which suggests that the best indicator of success for protecting biodiversity is to protect Indigenous languages and with them the unique approaches to the environment used for generations to successfully conserve biodiversity. Indigenous Nations and communities are thus uniquely positioned to take the lead on conserving biodiversity and protecting the environment for generations to come.

Q: As an advocate of “two-eyed seeing” — an approach to environmental work that combines Indigenous knowledge and perspectives with Western, scientific insights — can you explain how this approach can help address global climate change and its myriad ecological and social impacts?

According to Mi'kmaq Elder Dr. Albert Marshall, Etuaptmumk, the Mi'kmaw word for two-eyed seeing, means to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing and to see from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing — and to use both of these eyes together. Two-eyed seeing means not just acquiring book knowledge, but also actively pursuing knowledge by building relationships with knowledge-keepers — those who do not claim to own knowledge, but who share knowledge to ensure that it is transmitted respectfully and accurately.

Knowledge of the environment, for example, cannot only be about how best to exploit and extract value from that environment. There needs to be a deeper knowledge and appreciation for the value of the environment as a condition that sustains life — not only for ourselves, but for all the species that share our planet. A reciprocity of giving and taking has to be observed. Two-eyed seeing is a reminder to us that we are not alone; life is valuable to all life forms on this planet, and all life is in turn needed to sustain the ecosystem.

Nothing is alive by accident. Nature does not make mistakes. Some of us are not more important than others, and we humans, as a species, need to remember that we have a place in the ecosystem; we do not own it. In fact, we have responsibilities to the ecosystem. We have to learn to live in coexistence, in peace, and in cooperation with everything around us. Dominating and extirpating other species is not how we are going to "beat" climate change; climate change is happening because of such behaviors. It is up to us to change what we do and how we see things. In particular, we need to change the mindset that drives “progress” at any price. This mindset is not rational, given that we are paying the price in climate change and its myriad ecological and social impacts.

The people of the Maliseet Nation are also known as the Wolastoqiyik, which means “people of the beautiful river” in their language. They have long resided on lands on either side of the Wolastoq, or Saint John River, which runs through Maine and New Brunswick, and on land that extends northwest to the St. Lawrence River in Quebec.

Gallery: Native American and Indigenous Perspectives at MIT

Scholarship, education, and creativity in MIT's humanistic fields

Two-eyed seeing is the practice of applying more than the Western way of knowing to climate issues — allowing for another vision, another sight to be used to see what is happening and to address the impacts. This is done through a process of listening, hearing, and opening up the lines of communication between Indigenous and Western societies. From the time of contact, Indigenous Peoples have been the most generous, the most helpful, and remain the most committed to protecting the environment. Many Indigenous People and all those who stand up for the environment ask to be seen as protectors — and not criminalized for standing up for the environment. Civil protest and freedom of speech is an important element of protecting the environment for many seeking environmental justice.

Two-eyed seeing opens the door to meaningful collaboration and learning that has not happened before. It is time to pull together, have some solidarity, and create opportunity for anyone wanting to honor how our ancestors helped each other. Two-eyed seeing lets us see each other in a better, more inclusive way so that we all can help — which is critical since we all have roles to play in addressing climate change.

Q: In confronting an issue as formidable as global climate change, what gives you hope?

Seeing the sunrise every morning, hearing the sound of ocean waves, touching the bark on trees, and smelling the earth come to life in the spring give me hope. This is the ceremony of life. These things happen every day. We are the lucky ones who get to experience this ceremony.

I also have hope from seeing the growing number of initiatives that are utilizing the two-eyed seeing approach. The Wabanaki Youth in Science (WaYS) Program, developed by associate professor of anthropology Darren Ranco at the University of Maine with Wabanaki tribal communities, seeks to implement a curriculum for Indigenous students/youth that incorporates a two-eyed seeing approach.

WaYS has been revitalizing and maintaining Wabanaki ways of knowing while incorporating Western ways of knowing for an approach that is encouraging students/youth to pursue STEM fields. This is very important so that they will be prepared for climate change and the impacts to Indigenous communities, which may already be strapped for resources, including support networks that are culturally sensitive to their cultures.

Detail, of "A bend in the St. Lawrence River, Quebec," watercolour painting by Elizabeth Simcoe, ca. 1792; Simcoe Family fonds, the Archives of Ontario

Another initiative is being led by Dr. Evan Adams, chief medical officer for the First Nations Health Authority in Canada, who has been using the two-eyed seeing approach in his work with health professionals across Turtle Island. Adams and Simon Fraser University Faculty of Health Sciences are teaming up with the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council to lead a new project aimed at improving Indigenous children’s development and health. The project is part of a global initiative to reduce chronic disease and foster health and wellness.

The project is called Hishuk-ish tsawalk (everything is one, everything is connected), and its goal is to improve health and wellness among Indigenous children by optimizing their early environment to reduce the risks of chronic disease outcomes including such mental health issues as anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicide as well as cardiometabolic diseases such as obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and heart disease. This work is particularly important because the high levels of pre-existing chronic diseases in Indigenous communities puts them at higher risk to be impacted by Covid-19 and such climate-change-related illnesses as asthma, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and conditions triggered or exacerbated by extreme heat and cold.

As for me personally finding hope, I have also been taught that what we do with love matters. Fear is the opposite of love, and it can stop you in your tracks, keeping you from doing what needs to be done. We need to work with love. I am inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who said: “We must discover the power of love, the power, the redemptive power of love. And when we discover that, we will be able to make this old world a new world.”

My hope is that people will put aside their fears — of change and of each other — and work together with love to heal the planet.

Suggested links

Patricia Saulis

Excecutive Director, Maliseet Nation Conservation Council, Canada

Gallery: Native American and Indigenous Perspectives at MIT

Scholarship, education, and creativity in MIT's humanistic fields

Maliseet Nation Conservation Council

Maliseet Nation, website

Revitalizing the Wolastoquey language

Additional resources on Two-Eyed Seeing:

Indigenous Knowledge and Biodiversity (Unesco)

Indigenous Circle of Experts Report on Indigenous-led Conservation

Albert Marshall: Learning to See with Both Eyes — The Green Interview

Full Series Solving Climate | Humanistic Perspectives from MIT

Also See Fast Forward: MIT's Climate Action Plan for the Decade

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand, Communications Director

Consulting Editor: Kathryn O'Neill, Senior Writer

Published 6 April 2021