Investigating the intersection of law and technology

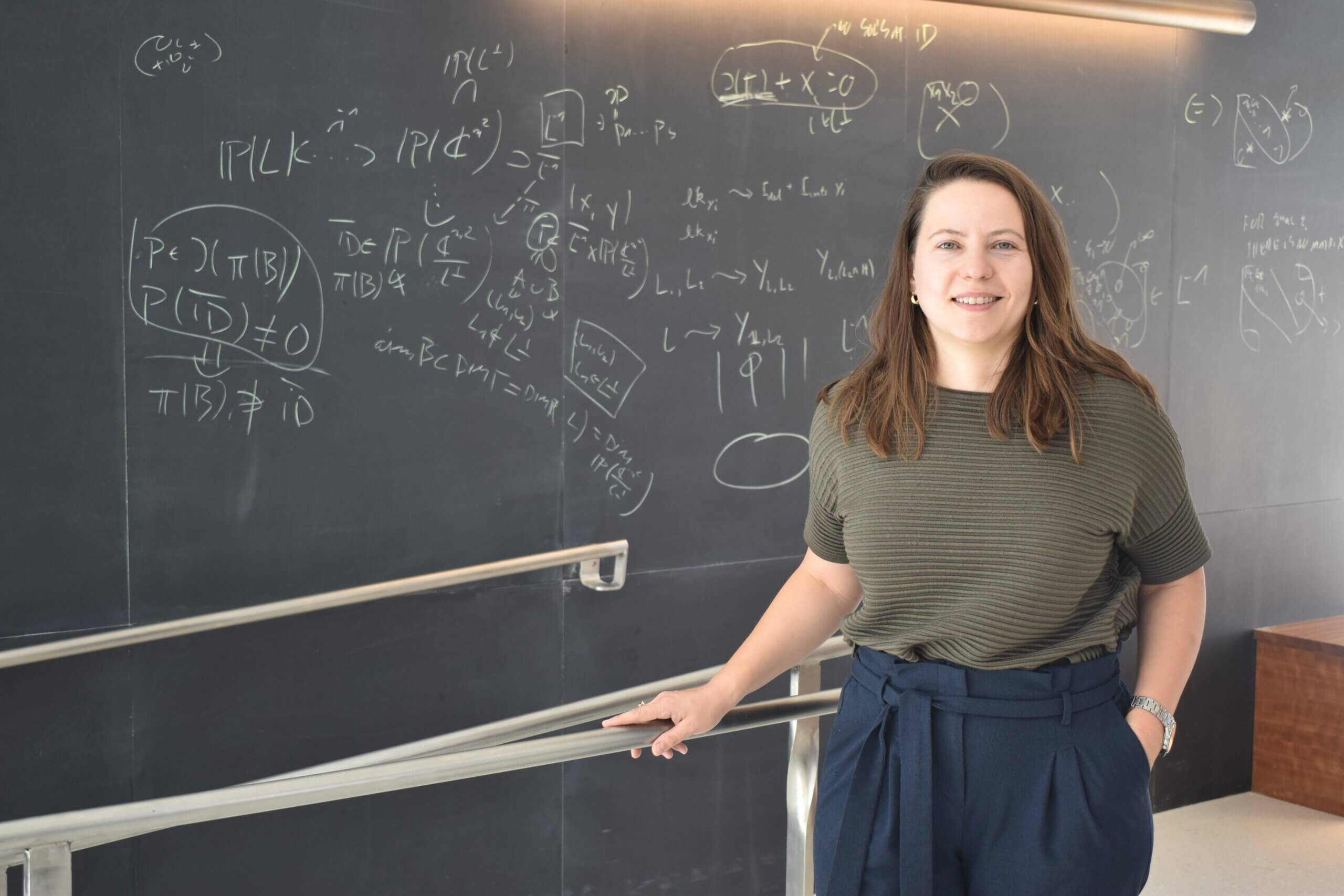

Alex Reiss-Sorokin PhD ’24 probes the impact of automation on both the practice of law and the people who make jurisprudence possible.

Automation doesn’t always mean improvement.

As a doctoral student in MIT’s History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology, and Society (HASTS) program, Alex Reiss-Sorokin discovered there is little work on how technology determines legal practice and shapes the practice of law. She focused on how lawyers and legal professionals are using technology in the field. “I wanted an empirical toolkit to study issues at the intersection of laws and technology,” she said. “I thought excavating and examining the past could help me gain insight into the present moment.”

Reiss-Sorokin carried her interest in these ideas and their impacts with her as a student at Tel Aviv University, where she studied law, history, and the philosophy of science. She also spent three years as a criminal defense attorney in Israel where her specialties included financial, political, and environmental crimes, as well as international extradition.

While her legal training prepared her to practice as an attorney, her research in history and philosophy exposed her to a wider social analysis of law and power. She later enrolled in a master’s program in international legal studies at NYU. There, Reiss-Sorokin learned not just the principles and theories that govern public international law, but also a different, holistic approach to its study. Her master’s thesis focused on Facebook’s regulation of speech online, using traditional legal tools to analyze policies set by an internet platform.

“That legal training helped me build an ideological and practical foundation for understanding and practicing law narrowly,” she says.

HASTS’ interdisciplinary approach to training was a big draw. “Legal training provided limited tools for the study of the relationship between law and technology,” she notes. “Sure, I could study legislation, case law, and law’s response to technological advancements. But, I was interested in law in action, the practice of law and its entanglement with technological tools.”

During her time at MIT, Reiss-Sorokin’s work was recognized both for its contribution to the study of law and society and the history of information technology. She was a fellow at the American Bar Foundation and received the two most prestigious fellowships for historians of information and computing technology: the Adelle and Erwin Tomash Fellowship in the History of Information Technology at University of Minnesota’s Charles Babbage Institute, and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Fellowship in the History of Electrical and Computing Technology.

As an MIT HASTS student, Reiss-Sorokin was a valued member of her department’s efforts to promote and encourage community connections. She helped organize the HASTS colloquium series for 2018-2019, the first Human-Computer Interaction Salon at MIT (led by professors in anthropology and the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), a public facing interdisciplinary lecture series called Cross-STS, and the 2019 Northeast graduate STS conference. In the summers, she was an instructor with Experiential Ethics, an MIT hands-on course on the ethical and social implications of technology.

Technology and reconsidering legal research and practice

Reiss-Sorokin’s research focused on LexisNexis, an online database and search engine of court decisions. She learned that rapid shifts in legal research coincided with the advent of digital storage systems and exposed gaps between large and small firms and their ability to effectively represent their clients. “LexisNexis was originally developed by the Ohio State Bar Association in an attempt to lower the costs of legal services and curb inequalities within the legal profession,” she says.

She learned that small firms and solo practitioners found it hard to compete with large firms, who had significant resources to devote to research, including large libraries and dedicated personnel. While the advent of legal databases helped make case law more widely accessible, it did little to diminish the chasm between firms. “Legal research was once inseparable from considerations of justice, access, and equity,” she said. “Those notions have been upended with the move to digital legal research, which treats legal research as a matter of information retrieval alone.”

Reiss-Sorokin notes that court cases and legislation are public, but access to them has always been facilitated through intermediaries like law reporters or digital platforms. “Developing cutting-edge search algorithms and digitizing thousands of books, the current ways in which this public information is made accessible and usable, requires a lot of labor and costs a lot of money,” she says. “Although the information is free, making it something lawyers could use is costly.”

She later discovered that her findings could be applied to the automation of work more generally. In law and technology, few scholars treated law as work, focusing instead on its governance and regulation functions. Centering the automation of legal research meant including not only lawyers, but also legal secretaries, librarians, technicians, and students.

“Legal research isn’t just a cognitive activity taking place in lawyers’ heads,” Reiss-Sorokin explains. “It’s a collaborative effort that relies heavily on legal secretaries, legal assistants (or paralegals), and clerks.” Automating legal research means significant changes to existing divisions of labor in law firms. Traditional notions regarding legal research have shifted.

In this sense, the excitement around and promise of this technology resembled the current discussion of automating lawyers’ work with artificial intelligence (AI). However, as with AI, improved efficiency hasn’t always occurred. Lawyers report spending more time doing legal research today than they did pre-automation. Computers shifted work rather than eliminated it.

Automation and impacts

Understanding what needed fixing in legal research changed as processes became automated. Lawyers partnered with technologists to solve related challenges, which changed the practice of law. Initially, the Ohio lawyers who developed the system that became LexisNexis sought to improve efficiencies by reducing the need for the physical labor required to conduct research, what Reiss-Sorokin called “hauling books off library shelves.”

“As they were interacting with the then emerging world of information pioneers, the problem with legal research became its reliance on an array of people and their subjectivity,” she continues. People who were once essential to the process of legal research were seen, by the end of this process of automation, as hindering legal research.

“What I think that teaches us,” Reiss-Sorokin says, “is that the changes automation brings aren’t just practical, but epistemological; they shape how we understand the work we do, not just how to do it.”

As a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University and the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) Reiss-Sorokin continues her research at the intersection of legal practice and technology. She’s preparing a book for publication, “Trust in Search: Credibility and Doubt in Legal Research Technologies,” which traces the ways technology has transformed legal practice. “Although search engines and databases are ubiquitous today, the question of what technologies people trust is critical for understanding our relationship with technology,” she says.

Related

-

March 24, 2025 | Benjamin DanielRay Kurzweil ’70 receives the 2025 Robert A. Muh Alumni Award

March 24, 2025 | Benjamin DanielRay Kurzweil ’70 receives the 2025 Robert A. Muh Alumni Award -

August 18, 2025 | Benjamin DanielRay Kurzweil ’70 to deliver Robert A. Muh Award Lecture

August 18, 2025 | Benjamin DanielRay Kurzweil ’70 to deliver Robert A. Muh Award Lecture -

February 5, 2026 | Willamina HadleyMIT alum Jennifer Mnookin PhD ’99 named president of Columbia University

February 5, 2026 | Willamina HadleyMIT alum Jennifer Mnookin PhD ’99 named president of Columbia University

Share a Story

Do you have a story to share about an event, a publication, or someone in the community who deserves a spotlight? Reach out to the SHASS Communications Team with your idea.

Email SHASS Communications