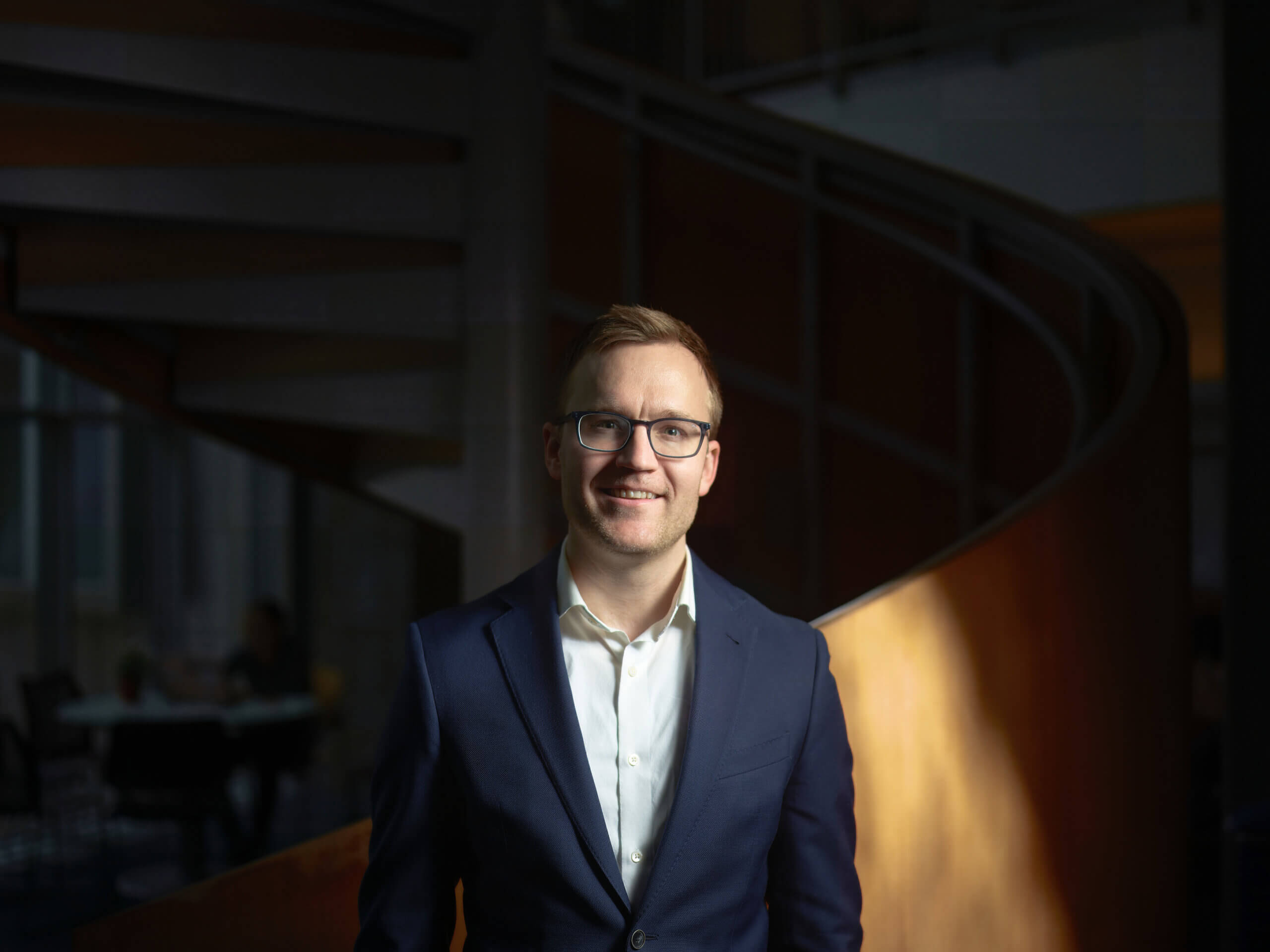

MIT philosopher Kevin Dorst PhD ’19 awarded 2026 Levitan Prize in the Humanities

For his research project, Dorst wants to answer questions about rationality and how people reason.

Philosopher Kevin Dorst PhD ’19 has been awarded the 2026 James A. and Ruth Levitan Prize in the Humanities. The prize, which carries a $30,000 research award, is awarded annually to support innovative and creative scholarship in the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.

The Levitan Prize was inaugurated in 1990. The fund was established through a gift from the late James A. Levitan, a 1945 MIT graduate in chemistry and a member of the MIT Corporation.

Dorst, an associate professor of philosophy, plans to critique the idea that, when evidence is plentiful, if people take reasonable steps to figure out the truth, they’ll usually succeed. He says this notion fails when introduced to the real world. It relies on support from ‘Bayesian convergence theorems’, claiming to show that ideal reasoners would gravitate toward fact-based information when making choices.

Bayesian convergence theorems implicitly and essentially assume clarity – that reasonable people know exactly what they think. Dorst disagrees with this assumption.

“This work will help us answer questions about rationality and how people reason,” Dorst says. “The Levitan Award offers an opportunity to improve my understanding of how to conduct different kinds of research effectively while also working closely with others from across disciplines to better understand human behaviors.”

In announcing the award, Agustín Rayo, the Kenan Sahin Dean of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, said “a review committee of senior faculty was particularly impressed by the project’s persuasive strength and the clarity with which it speaks to the concerns of our current moment.”

Dorst works in epistemology and cognitive science, focusing on questions about rationality: what it is, why it matters, and whether we have it. He develops and deploys better models of rationality to help refine our interpretation of the empirical results, and square them with humans’ experiences of (ir)rationality.

Dorst earned a PhD in philosophy from MIT in 2019 and a BA in philosophy and political science from Washington University in St. Louis in 2014. He joined the faculty in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy in 2022.

Shrinking the gap between philosophical theory and real-world practice

Dorst describes his project as “an interdisciplinary exploration of how modeling ambiguity can cause Bayesian convergence results to fail.” His research wants to deconstruct and rebuild an assessment framework that more closely approximates real-world reasoning conditions. While existing models offer idealized clarity, they don’t comport with how real people reason. He wants to test the idea that there’s a quantifiable gap between ideal reasoners, who may only exist in theory, and real people, whom Bayesian theorists would describe as irrational. While ideal Bayesians may behave this way, real people do not.

These phenomena may help explain humans’ social and political polarization, divides we may be able to bridge with rational processes. “This can impact everything from how we organize our institutions to how we discuss our political opponents,” Dorst continues.

Sometimes, Dorst says, our ideas about things are clear and unambiguous. They’re often unclear, however.

“If I ask you how often a coin flip will turn up ‘heads’, you’ll probably say half the time, right?” he asks. “But if I ask you how likely you think it is that I own a dozen spoons, things get a little more interesting.” There are mitigating factors at work that shape folks’ answer to the spoon question, factors that existing Bayesian modeling tends to ignore.

Additionally, there are ways to quantify ambiguity. Measures of cognitive uncertainty, prevalent in behavioral economics, use ideas like confidence to identify the uncertainty associated with ambiguity. “A researcher, after confirming how many times a subject thinks a coin might turn up heads when flipped, can then ask how confident the subject is in that assertion,” Dorst notes, “while a similar question about the number of spoons you think I own will likely yield a less confident response.”

The project includes:

- A series of experiments to test the theories under discussion, and

- A manuscript workshop where he’ll gather philosophers, cognitive scientists, and economists to review and discuss the work, which will yield

- A book, Reasonably Polarized: A Bayesian Theory of Bias.

The book this research will help produce, Dorst’s first, builds on work he began as a series of papers focused on ideas and ideological polarization. “Predictable polarization is everywhere: we can often predict how people’s opinions, including our own, will shift over time,” Dorst says about his work on quantifying responses to information and ideas. “I argue that cognitive search—searching a cognitively accessible space for a particular item—often yields ambiguous evidence.”

Dorst plans to enlist experts in philosophy, economics, and cognitive science to help refine the material, ensuring its ideas make sense and can be understood. He wants to avoid creating work that tries to appeal to all audiences and ends up appealing to none.

“It’s important to rigorously check my research results and the ideas they yield, eliminating bias where possible and ensuring my methods are sound,” he says.

Making space for compromise

Dorst emphasizes the importance of clarity in this work in everything from crafting survey responses to understanding the ideas under discussion between parties holding different views. “Teaching undergraduates has taught me the importance of clarity in views,” he says, describing the classroom as a proving ground for improving his research methods and ideas.

Dorst wants people to understand why they hold the ideas that shape their opinions, something he believes his work can help achieve. “I think it’s important to consider why we disagree, how we think about disagreement and polarization, and what we can do to find common ground,” he says. “There’s a gap between what we believe about how information should shape rational opinions, and how real people actually react to information.”

This assumption of “reasonable convergence” – the idea that when we polarize, it’s due to irrationality – doesn’t comport with what he’s observed in his research. People do respond to factual information, even if they often don’t do so as clearly as we’d like.

It’s possible, Dorst asserts, to choose points at which humans are more likely to respond favorably to information that diverges from their deeply-held ideas, to increase clarity and reduce ambiguity. “While we hope people will look rationally at and make informed choices about chores or climate change or tariffs, we’ve seen this isn’t always true,” he continues. “But if we present information at specific points while avoiding the trap of devaluing the other person’s beliefs and ideas, change is possible.”

Dorst hopes that philosophers and others find his work interesting enough to begin their own explorations. “I hope this leads to other valuable research for me and others interested in understanding why we behave the way we do,” he says. He also wants to eliminate the artificial barriers that currently exist between the disciplines informing his project.

“Psychologists have tons of data on people and their behavior – how real reasoning works – but it tends to remain insulated from philosophers and folks in other disciplines,” he says.

By repurposing existing theoretical models in use across economics and cognitive sciences, Dorst wants to help us reimagine what’s possible with people, their ideas, and how we understand and process them. The book and associated research represent an exciting, organized attempt to introduce cross-disciplinary work into research that affects all of us. “I get to work in so many different areas and learn more about how to effectively pursue this work,” he says. “We can answer questions about and address polarization together.”

Related

-

December 6, 2024 | Benjamin DanielMIT anthropologist Héctor Beltrán awarded 2025 Levitan Prize in the Humanities

December 6, 2024 | Benjamin DanielMIT anthropologist Héctor Beltrán awarded 2025 Levitan Prize in the Humanities -

January 8, 2025 | Benjamin DanielThirty-six outstanding MIT students selected as Burchard Scholars

January 8, 2025 | Benjamin DanielThirty-six outstanding MIT students selected as Burchard Scholars -

May 2, 2025 | Benjamin DanielSix MIT SHASS educators receive 2025 Levitan Teaching Awards

May 2, 2025 | Benjamin DanielSix MIT SHASS educators receive 2025 Levitan Teaching Awards

Share a Story

Do you have a story to share about an event, a publication, or someone in the community who deserves a spotlight? Reach out to the SHASS Communications Team with your idea.

Email SHASS Communications