COMPUTING AND AI: HUMANISTIC PERSPECTIVES FROM MIT

History | Jeffrey S. Ravel

Jeffrey S. Ravel, MIT Professor of History; photo by Jon Sachs

Action

"The nuanced debates in which historians engage about causality provide a useful frame of reference for considering the issues that inevitably emerge from new computing technologies. We may not be doomed to repeat the past if we do not study it. But we certainly miss an opportunity to imagine our way out of today’s existential threats if we do not appreciate the complexity of past crises."

Series | Computing and AI: Humanistic Perspectives from MIT

Professor Jeffrey S. Ravel is the head of the MIT History Section. His research focuses on the history of French and European political culture from the mid-17th through the mid-19th centuries. He is the author of The Would-Be Commoner: A Tale of Deception, Murder, and Justice in Seventeenth Century France (Houghton Mifflin, 2008) and The Contested Parterre: Public Theater and French Political Culture, 1680-1791 (Cornell University Press, 1999). He co-directs the Comédie-Française Registers Project, a collaborative venture between the Bibiliothèque-musée of the Comédie Française theater troupe, MIT, Harvard University, the University of Victoria, the Sorbonne, the Université de Paris-Nanterre, and the Université de Rouen. His newest Digital Humanities initiative is the Visualizing Maritime History Project.

. . .

Q: What are some examples of domain knowledge, perspectives, and methods from your field that should be integrated into the research and curriculum of the Schwartzman College of Computing and why?

The founding of the Schwartzman College of Computing (SCoC) offers a unique opportunity for the MIT History faculty to lead the way — both in the use of computational methods in the field of history and in providing the Institute with important perspectives as we embark on this new initiative.

Technological innovation can have unexpected political, social, and cultural impacts, as we see every day in headlines about social media and climate change. Is it possible to anticipate all the disruptions that computing innovations pioneered at the college will occasion? Of course not, but the nuanced debates in which historians engage about causality provide a useful frame of reference for considering the issues that inevitably emerge from new technologies.

When we study the French Revolution, for example, it is obvious that new print technologies used to disseminate secular Enlightenment ideas before 1789 played an important role as events unfolded. However, to understand fully the outbreak of revolution in 1789 — and the head-spinning implementation of state-sponsored terror in 1793 — one also needs to factor in the antiquated political institutions of the Old Regime, new global military pressures that arose at the end of the 18th century, the significance of the Atlantic slave trade for European economies, and the persistence of Catholicism among France’s largely rural population.

Historians today continue to debate why the democratic impulse of 1789 degenerated into terror just four short years later. Students introduced to debates like this one learn valuable lessons about the complexity of past causality — lessons that offer cautionary tales about the dilemmas we face today.

We may not be doomed to repeat the past if we do not study it. But we certainly miss an opportunity to imagine our way out of today’s existential threats if we do not appreciate all the complexity of past crises.

Q: What are some of the exciting, meaningful opportunities that advanced computing is making possible in your field?

Historians anticipate that the application of cutting-edge computational techniques in our discipline will enhance our understanding of the past without rendering currently productive approaches obsolete.

Like many other scholars in the academy, historians have profited from the digital revolution of recent years. Searchable corpora of texts and images, and databases of quantitative historical material and accompanying data visualizations have transformed the way we work. We still travel to brick-and-mortar archives and libraries for our research; the planet’s massive historical record is far from being fully digitized. However, these trips can now be conducted more efficiently thanks to online catalogs, search tools, and digital cameras that allow us to capture archival material expeditiously and organize it for future study. When we return home, we combine our soundings in physical repositories with the material available via online sources to expand our evidentiary datasets.

Historians today have far greater access to the raw material of the past than our predecessors had even a generation ago. This access has significantly advanced the work of the discipline, making it more complex and richer. But we still interpret the traces of the past through reasoned debate among ourselves and with others who find these issues critical to understanding the current moment and shaping our future directions.

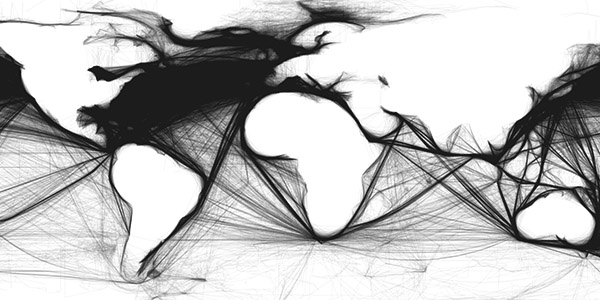

Ghost Shipping Paths: computational analysis of the growth of the American whaling industry; courtesy of Benjamin Schmidt, NU Lab

"Emerging innovations in computational methods will continue to improve our access to the past and the tools through which we interpret evidence. But the field of history will continue to be served by older methods of scholarship as well. To understand the past and to think about its lessons for our present and future, there are no computational shortcuts; critical thinking by human beings is fundamental to our endeavors in the humanities."

Emerging innovations in computational methods will continue to improve our access to the past and the tools through which we interpret evidence. Virtual and augmented reality, for example, might provide us with important digital spaces in which to interrogate the past and to question how thoroughly we can ever know the experiences of those who came before us. The data scientist’s concern, “garbage in, garbage out,” applies here. We will always need to be critical of our sources.

Paradoxically, working in a virtual environment may provide another way for us to understand the limits of historical knowledge, including the fragmentary nature of evidence that must be read critically. Elsewhere, advances in automated optical character recognition (OCR), perhaps enhanced by artificial intelligence and machine learning, might increase our access to the historical record locked away in physical archives around the world. The fully digitized, global archive may be a utopian dream, but the closer we can get to making the full historical record available to all, the more robust our interpretive debates will be.

While computational techniques offer new perspectives, however, the field of history will continue to be served by older methods of scholarship as well. To understand the past and to think about its lessons for our present and future, there are no computational shortcuts; critical thinking by human beings is fundamental to our endeavors in the humanities.

Suggested links

Series | Computing and AI: Humanistic Perspectives from MIT

Jeffrey Ravel

MIT History

MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Related works and publications

Ethics, Computing, and AI: Perspectives from MIT

20 Commentaries, All five MIT Schools

3 Questions: Jeffrey Ravel on bringing data to cultural history

MIT conference stems from data-rich historical project on French theater.

Interview: Jeffrey Ravel on French History

A global history conference at MIT

Mens et Manus in the History Workshop

MIT students build a printing press to learn about human systems

MIT Beaver Press

MIT Digital Humanities Program

Digital History, from the The Inclusive Historian's Handbook

by Sheila A. Brennan, digital public historian

Digital History Seminar Series | MIT History

"Writ large," Ravel said, "this seminar series is a space for us to reflect on our forthcoming engagement with the new college."

Online Courses and Resources from MIT History

Comédie-Française Registers Project

Visualizing Imperialism and the Philippines, 1898-1913, MITx/edX MOOC

Visualizing Japan, MITx/edX MOOC

Series prepared by SHASS Communications

Office of Dean Melissa Nobles

MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

Series Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand

Series Co-Editor: Kathryn O’Neill