COMPUTING AND AI: HUMANISTIC PERSPECTIVES FROM MIT

Literature | Shankar Raman with Mary C. Fuller

Shankar Raman S.B.'86, MIT Professor of Literature; photo by Jon Sachs

Action

"At least three priorities of current literary engagement with the digital should be integrated into the SCC’s research and curriculum: democratization of knowledge, new modes of and possibilities for knowledge production, and critical analysis of the social conditions governing what can be known and who can know it."

— Shankar Raman, MIT Professor of Literature

Series | Computing and AI: Humanistic Perspectives from MIT

Professor Shankar Raman S.B.'86 (Architecture, EECS), is the current head of the MIT Literature section and a MacVicar Faculty Fellow. His research focuses on late medieval and early modern literature. He is the author of Framing ‘India’: The Colonial Imaginary in Early Modern Culture (Stanford University Press, 2002) and Renaissance Literature and Postcolonial Studies (Edinburgh University Press, 2011). He is also co-editor of Knowing Shakespeare: Senses, Embodiment, Cognition (Palgrave Macmillan 2010). His current research explores the relationship between mathematics and literature in early modernity.

Professor Mary C. Fuller, who recently stepped down as head of the MIT Literature section, studies the history of early modern voyages, exploration, and colonization. Her current research explores the intersetions of geography, identity, and the history of the book. Her books include Voyages in Print: English Travel to America, 1576-1624 (Cambridge University Press, 1995) and Remembering the Early Modern Voyage: English Narratives in the Age of European Expansion (Palgrave, 2008).

. . .

Foreword

Earlier this year, Stanford University announced that it was discontinuing its pilot computer science joint major (“CS+X”) program, for reasons ranging from increased student academic burdens to the absence of true integration between fields. Only months later, Stephen A. Schwarzman — whose generous gift made possible our College of Computing — gave a complementary donation to Oxford University in order to jump-start a humanities center, which will include both traditional departments and an institute focusing on the ethical implications of artificial intelligence and other new technologies.

The first news item warns that conceiving the humanities as an add-on to computer science will not generate the transformative fusion of disciplinary knowledge that the Schwarzman College of Computing (SCC) seeks to encourage. We need to integrate the forms of knowing embodied by literature and aligned disciplines into the activities of the college from the ground up. In recognizing this principle, the founding of Oxford’s new humanities center affirms, too, the critical role of the humanities in today’s world, and limns a space that MIT should seek to make its own.

. . .

Q: What are some examples of domain knowledge, perspectives, and methods from your field that should be integrated into the research and curriculum of the SCoC and why?

In Literature, we study meaning-making in an expansive range of material, including visual and verbal objects, across a span of more than two millennia. Our research and teaching emphasize methods of analytical reading, using the evidence of narrative, formal structures, and readerly reception as well as material, historical, and social contexts. We share with other units in the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (MIT SHASS) the aim of fostering critical reflection, the practice of interpretive debate about our materials, and an awareness of the social and ethical dimensions of technology.

Over the last 30 years, digitization has dramatically broadened and transformed access to the kinds of materials that interest us. Reading books not available in a modern edition or on microfilm used to require that scholars travel to special collections armed with credentials to unlock access.

Mary Fuller, MIT Professor of Literature; photo by Jon Sachs

Action

"In the age of artificial intelligence, we could invent new tools for reading. Making the expert reading skills we teach MIT students even partially available to readers outside the academy would widen access to our materials in profound ways."

Today, major digitization projects have made huge numbers of printed texts from the 1500s onward available across the globe. Digitization has allowed access not only to words on the page but to evidence linked to their physical form. New kinds of data have become meaningful: the ability to look virtually under the written marks on a parchment, for example, has both revealed new texts and changed our understanding of how people used parchment in the past. Consider, for instance, that some previously unreadable 10th century works by Archimedes — almost obliterated by subsequent layers of writing and illustration — are now publicly available online.

Abundant information is only one side of the coin, however. Access and archives have never been truly universal — nor are they now. Digitization creates new versions of age-old problems: not everything is recorded; institutional and archival structures encourage some pathways while obstructing others. While there is always too much to know, the problem of who can know what remains pertinent.

This problem raises key questions in humanistic scholarship, revealing the selective nature of the information we access and the invisible forms of labor that make access possible. Algorithmic bias and bias in data sets have rightly concerned computer science and allied disciplines. Humanities disciplines can contribute their own history of grappling with both digital and analog equivalents of these problems, along with practical and intellectual interests in information management, from the architecture and classification systems of libraries to online search tools and design.

At least three priorities of current literary engagement with the digital should be integrated into the SCoC’s research and curriculum: democratization of knowledge, new modes of and possibilities for knowledge production, and critical analysis of the social conditions governing what can be known and who can know it.

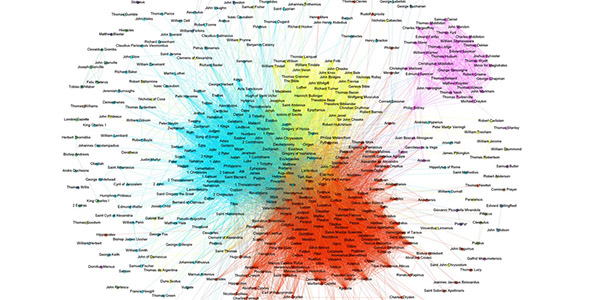

Figure: Doug Duhaime's visualization of "Co-Citation Networks, EEBO-TCP Corpus," 2014

"Today, major digitization projects have made [it possible] to look virtually under the written marks on a parchment... Consider, for instance, that some previously unreadable 10th century works by Archimedes — almost obliterated by subsequent layers of writing and illustration — are now publicly available online."

Q: What are some of the exciting, meaningful opportunities that advanced computing is making possible in your field?

The displacement of the codex volume as the default form of “the book” has catalyzed an explosion of innovative scholarship on the book in its broadest sense. Any textual object — scroll, e-text, or codex — comes into being through social and technological mediations that help determine its form, contents, and reception. Our research and teaching have grown increasingly sensitive to the evidence provided by texts in their varying forms, and digital methods have enabled some of the most exciting work with tangible materials, such as non-destructive ways of reading text on the interior surfaces of carbonized scrolls or folded letters.

Our colleagues have been leaders in developing new reading tools, multimedia digital archives, and innovative associated pedagogies. Advanced computing and the SCC offer the opportunity to enable new modes of learning, inquiry, and knowledge creation — by extending platform-level tools developed in Literature and elsewhere in SHASS, and by generating new research questions. For example, how does how we read affect the experience of what we read?

Most of our existing tools and strategies to aid reading — from footnotes to online forums — deal with content rather than form. Yet the ability to “read” the evidence of literary form distinguishes expert reading. Formal patterns are easy for machines to recognize and represent: In the age of artificial intelligence, we could invent new tools for reading. Making the expert reading skills we teach even partially available to readers outside the academy would widen access to our materials in profound ways.

Suggested links

Series | Computing and AI: Humanistic Perspectives from MIT

Shankar Raman

MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Related Publications

Shankar Raman wins Levitan Prize in the Humanities

The $25,000 award supports innovative scholarship

Raman named 2018 MacVicar Fellow

Raman, Autor, Capozzola, and Smith receive MIT's most prestigious undergraduate teaching award.

Mary Fuller awarded the Levitan Prize in the Humanities

Annual award includes $25,000 to support innovative and creative scholarship in the humanities.

Ethics and AI: The common ground of stories by Mary C. Fuller

“Stories allow us to model interpretive, affective, ethical choices; they also become common ground, conceptual meeting places that can serve to gather very different kinds of interlocutors around a common object. We need these.”

Fuller to lead NEH Seminar - English Encounters with the Americas

"English Encounters with the Americas, 1550-1610" is a National Endowment for the Humanities summer seminar for college professors.

Spenser’s "Faerie Queene" as a modern visual comic

Ivy Li, a literature and physics major, adapts a legendary work and innovates in an enduring literary tradition.

Stanford CS+X pilot to be discontinued end of spring quarter

Stephen Schwarzman gives $188 million to Oxford to research AI ethics

Series prepared by SHASS Communications

Office of Dean Melissa Nobles

Series Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand, Communications Director

Series Co-Editor: Kathryn O'Neill, Associate News Manager

Published 23 September 2019