ETHICS, COMPUTING, AND AI: PERSPECTIVES FROM MIT

A Dream of Computing | D. Fox Harrell

D. Fox Harrell; photo by Bryce Vickmark, MIT News

"We must be vigilant stewards of the future of computing at MIT. We must reimagine our shared dreams for computing technologies as ones where their potential social and cultural impacts are considered intrinsic to the engineering practices of inventing them."

— D. Fox Harrell, Professor of Digital Media and Artificial Intelligence

SERIES: ETHICS, COMPUTING, AND AI | PERSPECTIVES FROM MIT

D. Fox Harrell, is professor of digital media and artificial intelligence in the Comparative Media Studies program and in the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT. He is also the director of the MIT Center for Advanced Virtuality, which pioneers innovation in extended reality (XR), videogames, social media, and other new forms of technology that use computing to construct imaginative experiences atop the physical world. He is the author of Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation, and Expression (MIT Press, 2013).

• • •

Q: What is the scope of computing, and what social and ethical challenges do you see emerging as computing has an accelerating role in shaping human culture?

The many-faceted academic discipline of computer science has provided us with powerful ways to describe, specify, and understand the limits of processes and data. Computing, a more encompassing concept, is an area of study and practice addressing the broader milieu of the computer. Because computing is now so pervasive, there are numerous perspectives on what computing is: for instance, some people focus on theoretical underpinnings, others on implementation, others still on social or environmental impacts. These perspectives are unified by shared characteristics, including some less commonly noted: computing can involve great beauty and creativity.

Computing often enforces a kind of crystalline beauty because of its precision. Yet, the beauty of computing can also exhibit the imperfection, entropy, and ambiguity of the physical world: Software may contain flaws, and hardware invariably degrades. Computing also involves creativity, in part because it involves choices about how to express procedures and data: for instance, prioritizing efficiency or impact on societal challenges.

It is particularly valuable to reflect upon the nature of computing now because we are on the cusp of the formation of a College of Computing at MIT, the grandest restructuring of the Institute in decades. At MIT, computing has had impacts that cut across all five schools and our many departments, labs, and centers, each with numerous stakeholders who view computing differently. In practice, therefore, computing is defined in different ways by different ecologies of people, practices, and even artifacts.

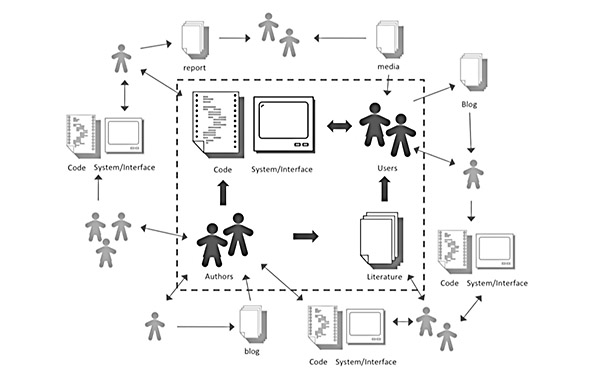

Defining what computing is depends on an ecology of people, machines, artifacts, and discourse. Figure credit: Jichen Zhu, from: Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation, and Expression, D. Fox Harrell (MIT Press, 2013).

For instance, an outcome deemed an artificial intelligence (AI) system might involve computers, teams of researchers and developers, users, technical reports, software, and writings in conference proceedings, social media, and more, all of which are interconnected. Consider, for example, the famous chatbot Eliza, which used simple text manipulation to simulate a conversation with a psychotherapist. Eliza has sometimes been described as an AI system for reasons outside of its technical complexity and without reference to the original publication – much to the chagrin of its creator, Joseph Weizenbaum.

Weizenbaum’s aim in creating Eliza was not to show that such a program was “intelligent,” and hence an AI system, but rather to show a clever approach to text manipulation and (later) to consider how this revealed something about the psychological traits of humans. As MIT’s College of Computing moves forward, it will be important to remember how dynamic our conceptions of what is central or peripheral to computing and areas such as AI are, based on the passage of time and the changing of communities.

A dream for the future

Given how broad an endeavor computing is, it follows that it holds great power to both ameliorate and exacerbate social and ethical challenges. I would like to zoom in on just one such challenge before reflecting on the future of computing at MIT. Computing has long been intertwined with society’s dreams of the future. I have argued that one of our society’s dreams could be called the “Avatar Dream,” a culturally shared vision of a future in which, through the computer, people can become whoever or whatever they wish to be. [Adapted from:

D. Fox Harrell and Chong-U Lim. 2017. Reimagining the avatar dream: modeling social identity in digital media. Communications of the ACM 60, 7 (July 2017), 50-61. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3098342.]

The current expression of the Avatar Dream involves using virtual identities (including online shopping accounts, electronic health records, social media profiles, avatars, etc.) to communicate, share data, and interact in computer-based (virtual) environments. The Avatar Dream poses major social and ethical challenges. I argue that we need to reimagine the Avatar Dream as one where the potential social and cultural impacts of virtual identities are considered intrinsic to the engineering practices of inventing them.

It is important that virtual environments — and the virtual identities within them — can convey or even augment how we express ourselves. Yet, some user groups are underrepresented or unfairly stigmatized by algorithmic bias and the actions of other users. Toward addressing these social and ethical challenges, I have pursued two strands of research. The first is computationally analyzing social phenomena in virtual identity systems. For example, we have employed machine learning (ML) approaches to study how people use social media differently in diverse cultures globally so that developers can best support how they negotiate their own cultural value.

Using such ML techniques we have also empirically revealed sexist and racist biases embedded in computing systems at large, including bestselling video games (a global market that now outstrips the film industry), demonstrating an approach that is highly generalizable. The second endeavor is computationally simulating social phenomena; it includes developing extended reality systems, video games, interactive narrative systems, and more with aims of creating richer experiences for users, conducting social science research, supporting diverse learners, and measurably enhancing users’ reflections on self and society. This work has led to new ways to model the systematic aspects of social phenomena (implementing what some of my colleagues have called social physics engines). Supporting such interdisciplinary research is just one way I believe MIT’s College of Computing can begin to address social and ethical challenges.

Image from "Mimesis," an interactive, narrative game exploring social discrimination; ICE Lab

"There are numerous perspectives on what computing is: for instance, some people focus on theoretical underpinnings, others on implementation, others still on social or environmental impacts. These perspectives are unified by shared characteristics, including some less commonly noted: computing can involve great beauty and creativity."

— D. Fox Harrell, Professor of Digital Media and Artificial Intelligence

Models for Connection: Bridge, Rhizome, Aquifer

To structure the new college, we need a model for how computing endeavors span the Institute. Analogies are one way to communicate such models, the efficacy of which can be judged by how easily they are grasped and the inferences that they enable. The College of Computing has been proposed as having a core and bridges, roughly corresponding to computer science (core) and its applications (bridges). While this analogy has the advantage of using monosyllabic terms (easy to grasp and remember), it has the disadvantage of placing those on the bridges at the periphery – although research in those areas may be of profound importance.

Moving forward, alternate analogies may prove more equitable and empowering. Acknowledging that there are disadvantages to strong analogies based in less familiar concepts, I’ll nonetheless go out on a limb and propose two. First, one could think of the College of Computing as a rhizome – a horizontal stem of a plant from which roots and shoots grow. Roots might represent work in traditional disciplines, and shoots might represent work in emerging disciplines, interdisciplinary research, or transdisciplinary practices. This captures the idea of a non-hierarchical structure, while recognizing that some types of research and practice are foundational while others aim for everyday impact.

Alternatively, one might think of the new college as an aquifer – water-bearing rock stretching horizontally underground. Aquifers can provide valuable water (computing, including computer science and its processes and outcomes) if tapped into with artesian wells (research, practice, and development involving computing). Under positive pressure, as with a flowing artesian well, these outcomes can emerge naturally. Such wells provide water, but they can also bring communities together. At the same time – just as wells are not the only sources of water – computing is not the only wellspring of innovation at MIT. Although everyone at MIT uses computers nowadays, some valuable research can and will proceed without significant engagement with the College of Computing, a fact that must be respected.

Regardless of which analogy we use, ultimately we must be vigilant stewards of the future of computing at MIT. We must strive to enable the best of what computing has to offer, ranging from foundational insights into the nature of how processes and data interact to fundamental engagement with the greatest challenges to human society and the environment. Toward these ends, my hope is that the formation of the College of Computing can support what I described as two underappreciated characteristics of computer science that I believe also apply to computing more broadly: beauty and creativity. I believe these characteristics are hallmarks not only of computing at its best, but of MIT itself at its best.

Let us collectively ensure that the future of computing embraces a plurality of aspirations that are beautiful and creative, precise and imperfect, theoretical and applied, visionary and technical, foundational and impactful — and beyond.

Notes

The idea here that mathematical formalization, which is intrinsic to computer science, is beautiful was inspired by a comment in: Goguen, J. A., "Tossing Algebraic Flowers Down the Great Divide," University of California, San Diego.

It must also be said that many aspects of such phenomena are subjective and culturally contingent in ways that resist computational modeling – in this regard there are many advantages to other artistic and humanities-based methods.

Suggested links

Series:

Ethics, Computing and AI | Perspectives from MIT

D. Fox Harrell:

Center for Advanced Virtuality

Website

ICE Lab (Imagination, Computing, Expression)

Comparative Media Studies / Writing

Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab

Stories:

MIT Open Learning launches Center for Advanced Virtuality

The new center will explore how MIT can use virtual reality and artificial intelligence and other technologies to better serve human needs.

3Q: D. Fox Harrell on his video game for the #MeToo era

The computer scientist’s group has designed a game that gets players to reflect on sexual misconduct in the workplace.

Designing virtual identities for empowerment and social change

D. Fox Harrell receives $1.35 million in grant funding to advance research at the intersection of social science and digital technology.

Building culture in digital media

Fox Harrell’s new book presents a ‘manifesto’ detailing how computing can create powerful new forms of expression and culture.

A new kind of media theory

MIT professor Fox Harrell works to enrich the subjective and ethical dimensions of the digital media experience.

Ethics, Computing and AI series prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Office of Dean Melissa Nobles

MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

Series Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand, Communication Director

Series Co-Editor: Kathryn O'Neill, Assoc News Manager, SHASS Communications

Published 18 February 2019