ETHICS, COMPUTING AND AI | PERSPECTIVES FROM MIT

In Praise of Wetware | Caroline A. Jones

Humans must truly understand intelligence to re-create it.

Photo by Joe Elliot, National Humanities Center

“As we enshrine computation as the core of smartness, we would be well advised to think of the complexity of our ‘wet’ cognition, which entails a much more distributed notion of intelligence that goes well beyond the sacred cranium and may not even be bounded by our own skin.”

— Caroline A. Jones, Professor of Art History

SERIES: ETHICS, COMPUTING AND AI | PERSPECTIVES FROM MIT

Caroline A. Jones is a professor of art history in the History, Theory, Criticism section of the Department of Architecture at MIT. She studies modern and contemporary art, focusing on its interface with technology and science. Her publications include The Global Work of Art (2015); the co-edited MIT press volume Experience: Culture, Cognition, and the Common Sense (2016); and Sensorium: Embodied Experience, Technology, and Contemporary Art (MIT Press, 2006), among others.

• • •

Q: What opportunities do you see for applying insights, knowledge, and methodologies from the arts and humanities to inform computing technology and artificial intelligence works?

Over the seven decades spent honing computation and AI, we have invented new problems while solving old ones. We seem to agree, at least in principle, that we want a public educated in the history and present cultural complexity of our problems. Democracy trusts in such an informed public — but history shows that there will always be a struggle as “these truths we hold to be self-evident” are contested and reframed.1

The “dry” facts of positivism and empiricism confront a “wet” world of rising seas, superstorms, leaking and floating migrant bodies, and messy resource wars. How can we evolve our “dry” technologies the better to engage complex networks of saturated life, whose scale and complexity already evade our comprehension and stewardship?

The touted achievements of artificial intelligence (AI) fit into the structure of “dry” solutions; as such, they spawn new problems. What to do when smart cities seem to foster abuse-by-surveillance (not to mention their vulnerability to ransomware that holds hospitals and statehouses hostage)? How to regulate friendly social networking platforms that turn out to be algorithmically biased toward the political fringes, amplifying hate and bigotry? Time-saving communication spawns useless “updates” and burdens our in-boxes with hundreds of messages of unknown importance.

Animal agriculture and petroleum extraction aren’t themselves dry labors, but their automation removes workers from traditional whistleblower roles, yielding unmonitored pollution that further stresses the planet. So called “disruptive technologies” can seem attractively priced, until we realize that some of those business models aim to replace leaky workers who need higher wages and healthcare with dry, automatic vehicles that will not.

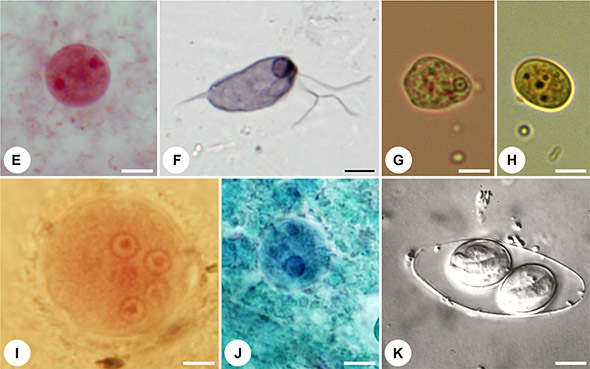

Detail of illustration showing human eukaryotic gut symbionts, from J. Lukeš et al. (2015). In order, E-K: (E) tritrichomonadid Dientamoeba fragilis; (F) retortamonadid Chilomastix mesnili; (G) amoebozoans Entamoeba hartmani; (H) Endolimax nana; (I) Entamoeba coli; (J) Entamoeba dispar; (K) coccidian Isospora belli. Source images from Ivan Čepička (E,F: Charles University, Prague); Marianne Lebbad (G,H: Public Health Agency, Solna, Sweden); Martin Kostka (I: University of South Bohemia, České Budějovice); and Jiří Vávra (K: Charles University, Prague).2

"Humans have never been simple. Unlike the machines we build, humans are pulsing with fluids and symbionts, riddled with ancient evolutionary paths working in concert with an awesome neo-cortex. Let’s face it, computational models of cognition have never been fully adequate to the wetware within, or the biological environment without."

— Caroline A. Jones, Professor of Art History

Bringing wetness into the equation

Humans have never been simple. Unlike the machines we build, humans are full of wet, chemical signals. We are pulsing with fluids and symbionts, leaky with secretions, riddled with ancient evolutionary paths working in concert with fancy new myelinated nerves and an awesome neo-cortex. Our architectures, workspaces, and medical technologies have never truly accommodated our damp, squishy, feeling parts.3 Let’s face it, computational models of cognition have never been fully adequate to the wetware within, or the biological environment without.4 The problems we have brought to our planet require that every discipline contribute, harmonize, concertize, critique, and collaborate in bringing wetness into the equation.

As an art historian, I study episodes in the past when debated truths were given lively form by artists committed to their roles as articulate citizens (and I teach students to track such lively aesthetics in contemporary art). “Modernism” in Western art offers useful examples of this dynamic, emerging vividly in France during a period when that nation was struggling to adjudicate the balance of public knowledge, federal control of information, and the very basis of a democratic republic born in the wake of a revolution.

The artist Honoré Daumier chose a particularly public medium — the industrially printed black-and-white lithograph in a mass-distributed periodical — to engage these debates. He did so most compellingly when he drew the searing image of Rue Transnonain with greasy crayon on a slab of limestone, wetting and inking the image for printing and distributing in 1834.

Honoré Daumier, Rue Transnonain, le 15 Avril, 1834, (Plate 24 of l'Association mensuelle), July 1834. Lithograph, 11 ¼ x 17 3/8 in. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

"The artist Honoré Daumier chose a particularly public medium — the black-and-white lithograph in a mass-distributed periodical — to engage debates about public knowledge, federal control of information, and the very basis of a democratic republic."

— Caroline A. Jones, Professor of Art History

An enduring image

In the velvety blacks and glowing whites that Daumier coaxes from the stone and prints onto the page, our gaze is focused on a central figure, slumped in death, with spreading stains on his nightshirt and puddling under his prone form. Illuminated as if by a central spotlight, he is surrounded by topsy-turvy furniture that recedes back into the shadowy corners of the room — his nightcap is awry, and we quickly come to interpret these fluids — they must be blood (such is the magic of how we fill in the information only hinted at by this two-dimensional, black-and-white abstraction of reality).

A life has fatally leaked away. Closer inspection reveals three other corpses — a mother (off to the left), a grandfather (staring sightlessly up at the ceiling, on the right), and a tiny baby crushed under the fallen man, its head bearing the marks of a bludgeon and contributing its own puddle to the chaos.

Daumier’s print was “viral” before that epidemiological term entered the lexicon. Everyone in Paris knew what massacre he depicted — any remaining doubt was cleared up by the print’s subtitle, 15 April 1834. On that night, government troops had tried to subdue citizens who had opposed a state crackdown on “association,” along with new censorship laws. Entering the working-class neighborhood linked to the protests, the French military homed in on a particular building on Transnonain Street where soldiers said a shot had originated the day before. Storming the building in darkness, these state troops murdered all of the inhabitants they encountered, down to the last man, woman, and child.

Daumier’s rendering of this untabulated massacre was so incendiary that Louis-Philippe, the “citizen king” of the fragile French republic, immediately ordered all copies destroyed. The street itself was renamed “Beaubourg” or “beautiful village,” and eventually the workers demanding access to information and association were dispersed in a highly motivated campaign of urban “improvement.” Daumier’s image has endured long after the neighborhood itself; the values he passionately agitated for slowly became central to the claims of liberal democracy in our own day. Humans should have the right to organize and inform themselves. Information should be free.

Layered history in the Paris streets: the 16th-18th century street name, rue Transnonain, supplanted by the modern 19th century regulation into Arrondisements (here the 3rd) and the re-branding of the road as “Beaubourg,” or, beautiful village.

"Our adaptive and responsive wetware, and its dependence on a larger living ecosystem, is something I recommend we try to understand more fully before claiming that it is 'intelligence' we’ve produced in our machines, or modeled by computation alone."

— Caroline A. Jones, Professor of Art History

Distributed intelligence

These current “self-evident” truths continuously demand our scrutiny. What do we mean when we refer to “intelligence” in machines, for example? Even Scientific American agrees that the simplicity of brain the master-controller is not adequate to our own intelligence, much less to the challenges raised by Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom who examines the “artificial” kind.5 As we enshrine computation as the core of smartness, we would be well advised to think of the complexity of our “wet” cognition, which entails a much more distributed notion of intelligence that goes well beyond the sacred cranium and may not even be bounded by our own skin.6

The world of art offers an excellent critique of the cranial paradigm. Multisensorial kinds of art today involve new media and immersive installations that lead visitors to acknowledge that they “know” the art through infrasonic vibrations in viscera (sound art), or through a diffused haptic response that seems to involve a highly distributed mirror system, or non-verbal proxemics. Thus while the artist might rely on sophisticated computation to sift data or transduce energies into human perceptual spectra, the experience of the art cannot be confined in a cerebral model of “intelligence.”

Intelligence that is independent of conscious thought

In parallel to the humbling proliferation of noncranial aesthetic forms are astonishing new insights from biology that confound the boundaries between mind and body or brain and viscera. Computation, cybernetics, and algorithms are all modeled on “dry” functions expressed in the binary bit, the electrical on-off signal, and the rigid cog, all the way back to the mechanical governor on James Watt’s steam-engine.7 The next revolution in contemplating “intelligence” has to grapple with new models such as the “enteric brain” epitomized by the gut-brain axis (in which mental health relies on partnerships with xenobacterial and eukaryotic microbiota), the “peripheral nervous system” where unmyelinated nerves rely on non-neuronal chemical signals, or the “immune brain” that thinks through our lymph system.

The adaptive learning system of our “meat machines” (e.g., the immune system) that gains and recalls knowledge about friends and foes every time we put something in our mouths, take something in via cuts in the skin, or breathe something into our nasal mucosa is a general intelligence — one that is shared among community members and seems to be completely independent of conscious thought, yet has everything to do with our lively sense of well-being. These “wet” models of intelligent learning, memory, and symbiotic collaboration should give the narrow definers of machine intelligence extreme pause.

Our adaptive and responsive wetware, and its dependence on a larger living ecosystem, is something I recommend we try to understand more fully before claiming that it is “intelligence” we’ve produced in our machines, or modeled by computation alone.

Suggested links

Series:

Notes

1. The reference is to Jefferson’s phrase opening the Declaration of Independence, and to historian Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States (W.W. Norton, 2018). I thank historians and cultural thinkers Rebecca Uchill and Ana María León for their thoughtful contributions to this text.

2. J. Lukeš, C.R. Stensvold, K. Jirků-Pomajbíková, L. Wegener Parfrey, “Are Human Intestinal Eukaryotes Beneficial or Commensals?” PLoS Pathog 11(8): (August 13, 2015) e1005039. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005039 available here [accessed Feb 13 2019].

3. Several recent books and articles attest to these points: Safiya Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York University Press, 2018); feminist architecture collaborative, “The Incubator Incubator, the Administration of Leaky Bodies, and Other Labor Pains,” Harvard Design Review, 46 (2018) online here: accessed January 8, 2019.

4. For one such argument, see Antonio Damasio, The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures (2017); see also John Brockman, ed., Possible Minds: 25 Ways of Looking at AI (Penguin Press, 2019).

5. Reviewing Nick Bostrom’s book, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies (Oxford University Press, 2015), Christoph Koch asserts that we need philosophy to anticipate the likely failures of our current AI. See “When Computers Surpass Us,” Scientific American Mind, 26: 5 (September 1, 2015): 26-29. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0915-26. As Koch argues, controlling AI “will be possible only once we have a principled, scientific account of the internal constraints and the architecture of biological intelligence. Only then will we be in a better position to put effective control structures in place to maximize the vast benefits that may come about if we develop smart companions to help solve the myriad problems humankind faces.” (emphasis added).

6. As his daughter so marvelously described Gregory Bateson’s work, mind is ““not necessarily defined by a boundary such as an envelope of skin.” Mary Catherine Bateson, 1999 foreword to Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (University of Chicago Press, 1972): xi.

7. See Jones, “Cybercultural Servomechanisms: modeling feedback around 1968,” in Eva Respini, ed., Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today (ICA, 2018).

Ethics, Computing and AI series prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Office of Dean Melissa Nobles

MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

Series Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand, Communication Director

Series Co-Editor: Kathryn O'Neill, Assoc News Manager, SHASS Communications

Published 18 February 2019