Humanities at MIT

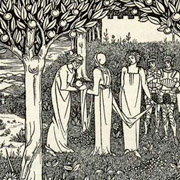

Le Morte d'Arthur and The Engineer

Literature assignment brings out the engineer in Laura Meeker '14

To complete round five in the game Laura Meeker designed,

players must make their way back to whatever square they

started on. As Professor Arthur Bahr explains, this rule gets

at the essence of the story. “The grand ideals of King Arthur

crumble under their own weight,” he says. “A Malory Morte

d’Arthur game that somebody wins would be untrue to the

text because ultimately, there are no winners. It’s about the

journey, and in the end, everyone loses something precious."

In the fall of 2013, after having taught "Medieval Literature: Legends of Arthur" at MIT for six years, Arthur Bahr took a leap of faith. Instead of a final paper, he gave his students the option to turn in a creative project about Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur.

“These are MIT students," says Bahr, Associate Professor of Literature."They’re makers. Mens et manus, right?”

About half of the students took him up on the option, which required students to create something related to visualizing time and space, a challenge for both readers of and characters in the book. He received decorative maps, elaborate charts, a storyboard for a television pilot, and in the case of Laura Meeker '14, a board game. Creating the game challenged Meeker as a student of literature and also as an engineer.

How the student came to put laser to wood, and what craft she achieved

Meeker, an MIT senior majoring in mechanical engineering and literature, had decided to start taking literature classes as a junior because she missed reading. It turned out that she enjoyed them so much, she just kept adding more. By the fall of her senior year, she’d written a lot of papers, so when Bahr provided the option to do something different, she took it.

The idea to create a game didn’t come right away, but Meeker knew she wanted to combine engineering and literature somehow. “I was thinking of things I could actually build and decided I could make a cool board for a game,” she says.

She designed the board on a CAD (computer-aided design) system. Using a laser cutter, she etched a slab of wood with a grid of positions, like a chessboard, but cut crosswise by a river on one side and sporting a 3-D scalable castle on the other. She fashioned playing pieces out of cards on stands, each an armored knight with a distinctive shield. “At one point I wanted to build jousting robots, but that was getting too much into engineering and too far from the text,” says Meeker.

While the making of the game physically involved skill and many late nights in the lab, the real design work — and the real mastery of the literature — is evident in the rules. Somewhat counterintuitively, the rules state: “There are no real winners. One may loosely consider the winner to be the player who reaches the end of round five first.” And, to complete round five, players must make their way back to whatever square they started on. In a sense, the game ends with the same sentiment as the book. “It’s really sad,” says Meeker. “Everyone sort of just sputters to a stop.”

According to Bahr, this rule gets at the essence of the story. “The grand ideals of Arthur crumble under their own weight,” he says. “A Malory Morte d’Arthur game that somebody wins would be untrue to the text because ultimately, there are no winners. It’s about the journey, and everyone loses something precious."

Arthur Bahr, Associate Professor of Literature, is the author of Fragments and Assemblages: Forming Compilations of Medieval London (University of Chicago Press, 2013). Story

Of the aventure that the student had, and how she read and read

To advance through the game’s rounds, each of which corresponds to a chunk of Malory’s narrative, players pursue a series of Aventures (the medieval term for adventure) that are inspired by key moments in the text. These quests involve jousting, acquiring horses for river crossings, ascending castle walls, and sometimes leaping from them.

Each player takes on an identity defined by an essential characteristic of one of the characters in the book. For instance, the player holding the Seductress identity card, modeled after the characters Guinevere and Isoud, holds the power to “stall the aventure” of another player for a few rounds.

To move, players roll dice, one, two or three, depending on the player’s identity and the current round. For example, the player holding the identity resembling that of Launcelot, who has a propensity for adulterous love, gets a bonus in the round that focuses on erotic affairs but is penalized in the more chaste round involving the quest for the Holy Grail.

Working out the rules took time and a lot of re-reading. “I kept finding flaws in my ideas and needed to make changes,” says Meeker. "But it was fun — and I wanted the game to work!" Her hard work paid off: Bahr plans to use the game in future iterations of the class, which means that Meeker's creativity and craftsmanship — mens et manus — will be be part of Literature at MIT for years to come.

Story prepared by MIT SHASS & MIT Engineering Communications

Communication Director, Engineering: Chad Galts

Communications Director, SHASS: Emily Hiestand

Writer: Elizabeth Dougherty