ELECTION INSIGHTS 2016

Research-based perspectives from MIT

On Political Rhetoric and Outsider Candidates | Heather Hendershot

Professor of Comparative Media Studies

"As a historian of American political media, it is always my instinct to ask how we can use the past to understand the present, and from this perspective it is useful to back up and consider how the rhetorical strategies of outsider candidates in earlier elections may help to put the Trump-Clinton election into context."

— Heather Hendershot, Professor of Comparative Media Studies

ELECTION INSIGHTS 2016

Research-based perspectives from MIT

Question

An unusual level of coarse, overheated, and factually unfounded language has emerged in the political speech of this election cycle. To what do you attribute the rise of such language in this election, and what is the historical context for such political speech? Based on your research, what is the most important perspective about the nature of U.S. political speech that would be useful for an American voter to know?

•

Every presidential election seems to bring with it the impression that political rhetoric has reached an all-time low, with candidates engaging in negative campaigning, manipulative spin, and empty puffery, and the media commenting, critiquing, informing, or, regrettably, fanning the flames of discord. Editorialists favoring one candidate will inevitably paint the other as woefully unqualified and certain to bring about the death of the republic.

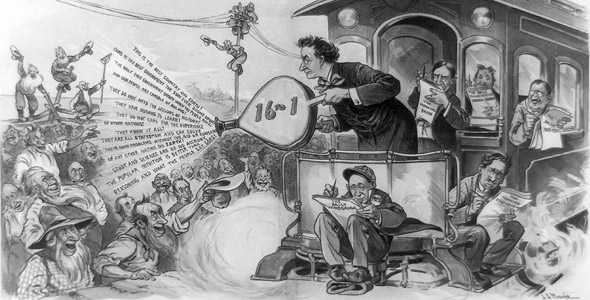

Consider how The New York Times once described a presidential candidate: “a charlatan, a play-actor, a demagogue, appealing to popular passion and prejudice … his mind is unsteady, his principles unsafe.” Trump? No, William Jennings Bryan, the populist Democratic nominee who the Times judged, in 1908, as “altogether inexperienced in administrative duty” and “unstable, flighty.”

Outsider candidates

The Trump and Bryan campaigns are over a century apart, and, though they might both be broadly branded as “populist,” it would be overreaching to compare them too closely. For one thing, Bryan had political experience; Trump, by contrast, fits into a group that one might generally label as “outsider candidates.” Outsider candidates are the ones most likely to use overwrought, fiery, excessive rhetoric. After all, they are not beltway politicians; they have the most to gain and the least to lose.

As a historian of American political media, it is always my instinct to ask how we can use the past to understand the present, and, from this perspective it is useful to back up and consider how the rhetorical strategies of outsider candidates in earlier elections may help to put the Trump-Clinton election into context. Looking backward does not always provide solutions, but it does provide perspective, potentially helping us to sort out the current moment, possibly tempering our alarmism but also perhaps exacerbating it.

I’d like to set the current Democratic nominee aside here. While Clinton is distinctive, in particular as the first female candidate to headline a major party ticket, she is also familiar, a party player with a long background in politics; her political discourse is about what you would expect. Further, whatever unique difficulties may have plagued her career, there is nothing unusual about a former secretary of state and two-term senator running for president. That’s business as usual. For a wealthy entrepreneur with little or no political experience whatsoever to run for president is, conversely, unusual business, but not that unusual. Let’s not forget Carly Fiorina, Herman Cain, or, reaching further back, Ross Perot, the Colonel Sanders of nutty third-party candidates.

What is unusual is not the existence of outsider candidates but, rather, for such candidates to succeed — or at least to succeed at high levels. In the 1990s, the Christian Coalition had great success getting its candidates placed on local school boards, but Pat Robertson’s presidential campaign flamed out with 9 percent of the votes in the primary. What successful outsider candidates do achieve is typically — but not always — dependent on clever use of populist rhetoric that draws heavily on language referencing insider/outsider status, notions of victimization, and a heavy-handed dosage of “common sense” and anti-intellectualism. This is, of course, often topped off with accusations of “liberal media bias,” although, to be clear, outsider candidates are just as likely to come from the left as from the right.

Cartoon depicting William Jennings Bryan's populist campaign

"Consider how The New York Times once described a presidential candidate: 'a charlatan, a play-actor, a demagogue, appealing to popular passion and prejudice … his mind is unsteady, his principles unsafe.' Trump? No, William Jennings Bryan, the populist Democratic nominee who the Times judged, in 1908, as 'altogether inexperienced in administrative duty' and 'unstable, flighty.'"

Would-be politicians

Consider two would-be politicians who did not play the outsider game particularly well. William F. Buckley ran for mayor of New York City in 1965 on the Conservative Party ticket. His campaign was articulate, charming, and high-minded. He refused to pander to various ethnic and religious subgroups by attending their parades, kissing their babies, or, as he put it himself, eating their blintzes. He was an “outsider,” and he pushed this idea, as well as the notion that the liberal media consistently misrepresented him, but he refused to paint himself or his followers as victims.

It was the rhetorical high road, but not any way to win an election. In the home stretch of the campaign, one of his managers suggested somewhat desperately in a memo, “whore yourself, and hold out the possibility of an electoral miracle…try a short sentence once in a while.” This, of course, was a tactic to which Buckley would not stoop.

Four years later, the Pulitzer-winning leftist writer Norman Mailer would also run for mayor of New York. Gearing up, he scrawled ideas, notes, addresses, and phone numbers on a palm-sized Efficiency Pocket Secretary notepad. One page read: “List of amateurs in politics — John Glenn, George Murphy, Ronald Reagan, Lester Maddox, Shirley Temple, Bob Mathias.” These were all amateurs — actors, athletes, and even a fried chicken entrepreneur — who had succeeded in going pro, but Mailer couldn’t swing such success for himself.

He got his populist rhetorical spin about 50 percent right, presenting himself as a crowd-pleasing, hard-drinking, male chauvinist, man-of-the-people running on the slogan “No More Bullshit.” But he proposed that both the right wing and left wing could benefit from his libertarian-infused proposal of total neighborhood control. You could, under Mayor Mailer, choose to live in a neighborhood where churchgoing was mandatory or in another where pot and free love were required. Mailer thought that the John Birch Society and the hippies could find a route to peaceful coexistence. This is not the polarizing rhetoric that gives outsiders a leg up.

"What is unusual is not the existence of outsider candidates but, rather, for such candidates to succeed — or at least to succeed at high levels. What successful outsider candidates do achieve is typically dependent on clever use of populist rhetoric that draws heavily on language referencing insider/outsider status, notions of victimization, and a heavy-handed dosage of 'common sense' and anti-intellectualism."

Populist demagogues

On the other side, consider Lester Maddox and George Wallace. Racist to the teeth, both found electoral success, though on different planes. Maddox was famous in Atlanta for chasing blacks (“You dirty Communists!” he hollered) out of his restaurant. He successfully ran for governor of Georgia in 1966 with KKK endorsement and little platform save his opposition to integration. He didn’t win because his pro-segregation language marked him as any different from the “real” politicians running for governor. He won because he successfully presented himself to the media and to voters as a little guy, an outsider, a man “protecting” his small business from the Washington bigwigs.

As Alabama governor, George Wallace was not the same kind of “outsider” as Maddox — he was an actual politician. But he was as skilled at populist demagoguery as Maddox and even better at painting the East Coast liberal media with the brush of elitism. When he ran for president in 1968 (and again in 1972 and 1976), he based his whole campaign on the notion of his own underdog, outsider status. The kooks came out in droves, and when he spoke at Madison Square Garden in 1968, white supremacists celebrated him outside by waving “I like Eich” (that is, Adolf Eichmann) signs. Within Alabama, he was seen by his white constituents as a legitimate politician.

Outside Alabama, running for president as a third-party candidate on an anti-big-government platform, his flamboyant rhetoric and talent for demonizing intellectuals and liberals appealed to disenfranchised white ethnic Americans, winning him just over 13 percent of the popular vote. This was disastrous for Nixon, who barely squeaked into office. It also showed that someone who rhetorically positioned himself as qualified precisely because he was not a Washington insider or the darling of the liberal media establishment could draw substantial votes in a national election.

American voters

So, where does all of this leave us in 2016? When we consider the success to this point of the Trump campaign, many obvious explanations come to mind: Trump has played the mainstream media like a fiddle, even as he constantly insults them, and he has excelled at using social media to bypass conventional news outlets.

Like Buckley, Mailer, Maddox, and Wallace, he understands the power inherent in painting oneself as an outsider, in his case a man who pretends he can succeed as president precisely because he is a businessman, not a politician. He is a skilled polarizer, every bit as good as Wallace, and, like Maddox, with a history of refusing black business.

My colleague Edward Schiappa aptly explains what makes this campaign special, or, more precisely, especially troubling. We might, however, point to the threat of the Trump campaign as lying in precisely what makes it not special. The crudest outsider candidates are often those who get the farthest; to use the Republican nominee’s words from the September 26 debate, those who are “braggadocious” can win “bigly.” Ultimately, only we, the American voters, can decide what standards of thought, language, and behavior we expect of our leaders.

Suggested links

ELECTION INSIGHTS 2016

Research-based perspectives from MIT

Comparative Media Studies /Writing Program

MIT News

Broadcasting rights

Heather Hendershot studies the conservative movement’s strategic use of television through the decades.

Changing the face of conservatism in the U.S.

Hendershot explores impact of William F. Buckley’s “Firing Line.”

The Wall Street Journal

Video Interview at Wall Street Journal

Wanted: A Modern-day "Firing Line"

Politico

William Buckley Was No Feminist, But He Was an (Unintentional) Ally

How to Vote in Every State

See video with info for your state — and vote!

Photograph of Heather Hendershot by Jon Sachs, MIT SHASS Communications