ELECTION INSIGHTS 2018

Research-based perspectives from MIT

Christine Walley | On Work, Stories, and American Identity

Professor of Anthropology

"Finding a path forward that can strengthen working and middle classes in the United States will entail finding alternative interpretative frames — new stories if you will — that allow people to make better sense of the economic realities they’re experiencing."

ELECTION INSIGHTS 2018

Research-based perspectives from MIT

QUESTION

In your research on communities that have suffered deindustrialization, you speak of the importance of stories and their centrality to people’s sense of identity. In your and Chris Boebel's documentary film, "Exit Zero," you say, “The stories we tell make us who we are.” Is the hyper-partisanship of our time a kind of story to help bolster diminished identities? And do you have thoughts about how other, more beneficial stories might emerge to help Americans thrive in a changing world?

COMMENTARY

The stories and interpretations that different groups of Americans offer of economic changes, including the loss of manufacturing jobs and growing inequality, are central to how they understand their own social positions as well as the kinds of economic and political futures they can envision and try to enact. I think many Americans are struggling for a way to understand and talk about these economic changes — changes that are also apparent in other wealthier countries but more extreme in the United States.

Recap: The build-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election

First, let’s look at some of the economic changes unsettling longstanding ideas of the “American Dream” and then at some of the barriers and possibilities for generating new kinds of American stories.

While many factors were at play in the 2016 election, including foreign interference and racial and gender divisions, the economy was clearly central. The loss of stable, well-paid industrial jobs — the kinds of jobs that fueled economic prosperity in the post-World War II era — has been a major destabilizing force in the United States for several decades.

It is estimated that nearly 7 million industrial jobs have been lost since 1980,1 and those losses have been central to growing economic inequality. What was often left out of media narratives around the 2016 election is that deindustrialization did not simply affect white male factory workers: its direct and indirect impacts have been widely felt by women and men of all races and ethnicities. In some areas like Chicago, for example, African Americans have been hardest hit.2

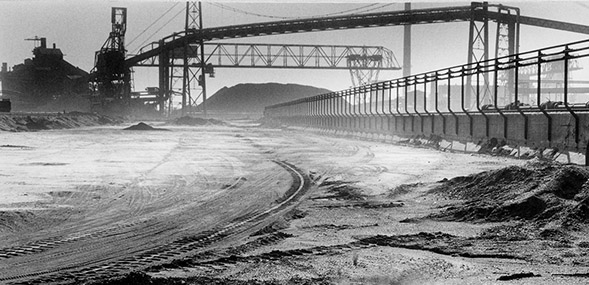

The former Wisconsin Steel mill, Southeast Chicago; photo courtesy of Southeast Chicago Historical Museum

"Heading into the 2018 election, the economy may be booming, but that boom continues to disproportionately benefit those on top, while many jobs being created remain of poor quality. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the net worth of a typical middle-class family is $40,000 below where it was before the crisis, with African Americans and Latinos by far the hardest hit."

During the 1980s and '90s when industrial jobs were being lost on a large scale, “new economy” prophets promised that deindustrialization would mean only temporary distress on the way to greater overall prosperity. For many, this proved patently untrue. In the formerly industrialized parts of the Midwest where I conduct research (and where I’m originally from) the long-term economic and social damage of deindustrialization is still heavily felt a generation or two after the original loss of industry.3

While some have gained the additional education and skills needed to “make it” in the contemporary economy, many others have been left with work that is far less stable, has fewer benefits, and is more poorly paid. Others have left the job market altogether. Newer types of jobs may also be less conducive to creating the kinds of collective social identities often found in older industrial communities.

A changing economy

I think many Americans are struggling for a way to understand and narrate these economic changes and how to locate their own place within this changing landscape. One common framework for understanding industrial job loss has been “globalization,” understood as either more competitive forms of global trade or the role of labor outsourcing in undermining wages and labor protections at home.

While important,4 another major factor has been corporate restructuring and “finance capitalism” in which corporate leaders, under pressure from Wall Street, have tried to maximize profits for shareholders through downsizing, outsourcing, or reducing obligations to workers, or by making money through buying and selling companies instead of making things. Anthropologist Karen Ho who studied Wall Street in the build-up to the 2008 financial crisis explored a key conundrum of recent decades: that a soaring stock market no longer necessarily leads to more or better jobs.

She argued this resulted in part from a cultural narrative she called the “shareholder value revolution” that became dominant on Wall Street, in which shareholder profits were re-envisioned as the defining purpose of companies at the expense of other stakeholders.5 More generally, corporate restructuring is key to understanding why there has been such a vast escalation in wealth at the upper end of the social spectrum during the same period when industrial jobs were being lost.

Corporate restructuring also helps explain why so many contemporary Americans are experiencing increasingly precarious forms of work. While industrial workers were hard hit beginning in the 1980s, this trend is increasingly a reality for the middle classes as well. Forty percent of Americans are now “contingent” workers, ranging from well-educated consultants to part-time workers to factory laborers who are themselves increasingly “temps.”6

As a result, college-educated office workers with unstable jobs and mounds of college debt are now also trying to make sense of the changing nature of work. The dominant narrative of meritocratic individualism central to the American Dream — that if you work hard, you can get ahead — cannot explain such difficulties and leaves people few ways to interpret their own situation except self-blame.7 In short, many middle-class individuals are also searching for new interpretive frames.

Opening sequence from the film Exit Zero, which explores the impact of de-industrialization on the communities of Southeast Chicago

"Finding a path forward that can strengthen working and middle classes in the United States will entail finding alternative interpretative frames — new stories if you will — that allow people to make better sense of the economic realities they’re experiencing."

A symbol of anxiety

In the 2016 election, the “white male industrial worker” emerged as a central figure in explaining Donald Trump’s victory. In my view, the galvanizing role of the loss of industrial work among voters wasn’t simply due to the fallout of deindustrialization. There was also a symbolic component. I would argue that the figure of the endangered white male factory worker came to symbolically encapsulate broader anxieties about a changing economy for many white middle-class voters who were increasingly fearful for their own jobs and stability.8

Disentangling the economic motivations of “working class” Trump voters stems in part from many media pundits using an overly broad definition of social class based not on occupation or income but on whether someone completed a four-year college degree. Given that 64 percent of non-Hispanic whites in 2015 did not have a college degree,9 this definition of white “working class” actually included many formerly considered “middle class.”

Polls and post-election data, for example, reveal that nearly 60 percent of Trump’s “working-class” supporters were, in fact, in the top half of the national income distribution.10 In other words, Trump’s message of economic nationalism seemed to appeal not only to those experiencing displacement but those who feared it in the future.

Clearly, the current period is one of hyper-partisanship, fueled in part by cable news and online outrage, wealthy donors trying to shift the political landscape, and the ways partisanship itself has become a form of identity politics. However, I’m not sure if partisanship is the best frame to make sense of the (de)industrial Midwest. Given the popular association of the term “working class” with “industrial workers,” whites in the formerly industrial Midwest are sometimes perceived as core Trump supporters despite a long history of being historically swing voters.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that many whites in the Midwest voted for Bernie Sanders in the 2016 primaries and twice as many Democrats stayed home or voted for a third party than switched parties to Trump;11 at the same time, many people of color who rejected Trump are also worried about the changing nature of work and opportunities for a good life. Many other working-class voters of all ethnic and racial backgrounds are simply cynical about the political process and don’t vote at all. In short, despite big data’s emphasis on demographics as predictors of political affiliation, partisanship doesn’t fall cleanly along demographic lines. Interpretations continue to matter.

"One major factor in current economic changes has been corporate restructuring and 'finance capitalism' in which corporate leaders, under pressure from Wall Street, have tried to maximize profits for shareholders through downsizing, outsourcing, or reducing obligations to workers, or by making money through buying and selling companies instead of making things."

An interpretive vaccum

Heading into the 2018 election, the economy may be booming, but that boom continues to disproportionately benefit those on top, while many jobs being created remain of poor quality. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the net worth of a typical middle-class family is $40,000 below where it was before the crisis, with African Americans and Latinos by far the hardest hit. It remains a time of uncertainties, uneven gains, and a growing gap between haves and have-nots. Finding a path forward that can strengthen working and middle classes in the United States will entail finding alternative interpretative frames — new stories if you will — that allow people to make better sense of the economic realities they’re experiencing.

There are many barriers, however, to making sense of these realities.

Political campaigns increasingly market themselves to the perceived biases of demographic groups rather than seeking to engage people in substantive political discussion.13 Media outlets that target working class people increasingly come from sources with overt (often right wing) political agendas, making it harder to gain accurate information needed to make informed choices.14 Unions continue to be a source of alternative narratives, but they have lost significant numbers due to both deindustrialization and changes in the law. This kind of interpretive vacuum has contributed to some trying to buttress their own battered sense of social worth or assuage anxieties by vilifying others.

Listening

Given these factors, one of the most valuable things we can do now is to listen to one another — and to provide ample spaces for alternative American narratives that better make sense of these economic realities. Listening is a key practice for anthropologists, of course, and my recent research trained that practice on stories from my own family in the former steel mill community of Southeast Chicago. Later, in response to the resulting book and film, hundreds of Southeast Chicago residents told me stories about the profound dislocations they and their families suffered after the steel mills closed. Intriguingly, not a single one invoked partisan politics.

I suspect that for many of these people in my hometown (and for myself), the desire to look back in time reflects a profound need to make sense of a complex and ongoing economic and social transformation. I think it’s the same for the United States as a whole. Generating work in the future that can provide a sense of dignity, purpose, and meaning, as well as greater economic stability, is among the largest challenges we face as a country. In grappling with that challenge, we will need both policy and insight. Taking stock of our history, going to the experiential core of our own stories — and listening carefully to the stories of others — are crucial first steps toward shaping a better future.

Suggested links

Christine Walley | MIT Website

Book and Film

Book: Exit Zero | University of Chicago Press

Preview of the "Exit Zero" film

News and Interviews

MIT News: Hard Times in Chicago

Anthropologist Walley's new book recounts the painful aftermath when steel plants suddenly closed in the American heartland.

Research Spotlight: The impact of deindustrialization

Interview with Chris Walley and Chris Boebel

"We’re excited about the possibility of narratives that move across genres."

Life and Death After the Steel Mills

In her study of a community devastated by industry's flight, anthropologist Christine Walley raises questions about how to create and support meaningful work in a postindustrial world.

Related Works

Making in America: From Innovation to Market

By Suzanne Berger (MIT Press, 2013)

With MIT Task Force on Production in the Innovation Economy; How America can rebuild its industrial landscape to sustain an innovative economy.

Made in the USA

by Vaclav Smil (MIT Press, 2013)

An argument that America's economy needs a strong and innovative manufacturing sector and the jobs it creates

How to Vote in Every State.

See video with info for your state — and vote!

____________________________

NOTES

[1]Mark Muro and Siddharth Kulkarni. 2016. “Voter Anger Explained in One Chart.” Metropolitan Policy Program, Brookings Institution, March 15th.

[2]Marc Doussard, Jamie Peck, and Nik Theodore. 2009. “After Deindustrialization: Uneven Growth and Economic Inequality in ‘Postindustrial Chicago’.” Economic Geography. 85: 183-207. William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor, New York: Vintage, 1997.

[3]Sherry Linkon, 2018, The Half Life of Deindustrialization: Working Class Writing about Economic Restructuring. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

[4]For example, David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson, 2013, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” American Economic Review, 103(6):2121-2168.

[5]Karen Ho, 2009, Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street. Durham: Duke University Press.

[6]Elaine Pofeldt. 2015. “Shocker: 40% of Workers Now Have ‘Contingent’ Jobs, Says U.S. Government,” Forbes, May 25th. Contingent work includes: part-time workers, independent contractors, agency temps, on-call workers, contract company workers, and self-employed workers.

[7]Silva, Jennifer M., 2013. Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[8]It is telling for example, that in earlier decades, middle-class people could be quite unsympathetic to displaced industrial workers. See Kate Dudley’s 1997 ethnography End of the Line: Lost Jobs, New Lives in Postindustrial America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) which was unusual in the deindustrialization literature in that it asked for the views of middle class professionals on displaced industrial workers.

[9]U.S. Census Bureau. 2015. Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015.

http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf;

[10]Nicholas Carnes and Noam Lupu June 5, 2017 “It’s Time to Bust the Myth: most Trump Voters were Not Working Class.” Washington Post. Simon Maloy, “The Trump Vote: New Data Reveal Hints as to Who Is Most Likely to Pull the Lever for Trump,” (Salon.com), http://www.salon.com/2016/08/15/the-trump-vote-new-data-reveals-hints-as-to-who-is-most-likely-to-pull-the-lever-for-trump/.

[11]Konstantin Kilbarda and Daria Roithmayr, Dec. 4, 2016, Trump Didn’t Flip Rust Belt Voters – Clinton Lost them. Slate: Business Insider.

[12]“The Recovery Threw the Middle-Class Dream Under a Benz,” by Nelson D. Schwartz, Business Day, New York Times, 9/12/18.

[13]Vidart-Delgado, Maria. 2016. When Marketing Becomes Democracy. Unpublished book manuscript.

[14]For example, see Appendix C in Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land (The New Press, 2016) in which she clarifies the misinformation about economic and political realities voiced by Tea Party supporters who were also heavy viewers of Fox News. Eli Rosenberg, 2018 “Trump Said Sinclair “is Far Superior to CNN.” What We Know about the Conservative Media Giant Sinclair, Washington Post, April 3.