How Africans developed scientific knowledge of the deadly Ttetse fly

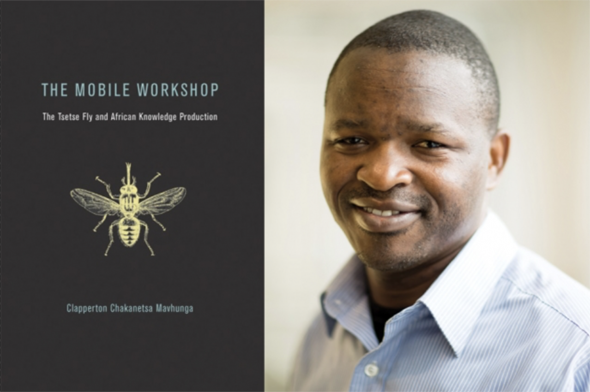

Associate Professor Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga explores science in action in Africa.

“I wanted the reader to appreciate how language, deployed as a tool to silence African modes of knowledge, can be mobilized as a tool to recover that same knowledge. In a sense, the book hopes to excite younger scholars — and Africans! — to investigate, imagine, and make science from Africa."

— Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, Associate Professor, Program in Science, Technology, and Society

Few animals are more problematic than the tiny African insect known to English speakers as the tsetse fly. This is the carrier of “sleeping sickness,” an often deadly neurological illness in humans, as well as a disease that has killed millions of cattle, reshaping the landscape and economy in some parts of the continent.

For generations, vedzimbahwe (the “Shona” people, builders of houses) and their African neighbors, assembled a significant store of ruzivo — knowledge — about mhesvi, their name for the tsetse fly. As MIT Associate Professor Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga explains in a new book, this accumulation of local knowledge formed the basis for all subsequent efforts to control or destroy the tsetse fly and is an exemplary case of scientific knowledge being developed in Africa, by Africans.

“Ruzivo and practices based on it were the foundation of what became science and means and ways of tsetse control,” Mavhunga writes in “The Mobile Workshop: The Tsetse Fly and African Knowledge Production,” recently published by the MIT Press. However, he notes, Europeans nonetheless dismissed Africans as being “only good at creating and peddling myths and legends.”

Suggested links