Reflections | Anne McCants

Notes from a historian — and director of the MIT Concourse Program — for her students and others during the pandemic

"As an historian, I know full well that the dislocation of people from their homes, often accompanied by stringent restrictions on their mobility as well, is a recurring feature of our collective life. So too is facing uncertain outcomes with forces we do not fully understand, whether they be at the microbe scale or the cosmic scale. Communities have faced our current stress before and found ways to cope, and even emerge with new ideas and new ways of doing things."

— Anne McCants, Professor of History; Director of the MIT Concourse Program; President, International Economic History Association

Research and Perspectives for the Pandemic

Main Page | Daily Life

Browse entries by date

March 18 | March 22 | March 26 | March 30 | April 2 | April 6 | April 9

April 12 | April 16 | April 20 | April 24 | April 30 | May 4 | May 7 | May 10

May 14 | May 17 | May 22 | May 29

"This is likely to be one of the odder spring terms in your undergraduate career. But I hope that you are finding ways to connect with those you love, engage with world events, keep your cool under strain, and find small (or large) things to be joyful for that had not been part of the original plan."

Good afternoon Concourse,

It is now one week since most of us departed campus for places near and far. And it is officially the eve of spring break. It seemed a propitious moment to write to you again, in what I have decided to call my "Notes from the Director's Kitchen” — since I do so much of my computer work from my kitchen counter while other things are stewing or brewing.

This is likely to be one of the odder spring breaks in your undergraduate career. And certainly it is not the spring break you had planned for yourself. But I hope that you are finding ways to connect with those you love, engage with world events, keep your cool under strain, and find small (or large) things to be joyful for that had not been part of the original plan.

For me, an unexpected joy has been watching a number of my MIT colleagues, many of whom I did not know all that well only three weeks ago, step up to the present challenge in the most impressive and amazing of ways. Like most employees, I have my regular gripes about my employer. But in a world of whip-lash rapid change and formidable challenge, I’ve been struck by how fortunate I am to work at a place like MIT, full of smart, compassionate, and extraordinarily dedicated people, many of whom are now doing jobs (and doing them well) that they never trained for.

Spotted on a walk along the Ipswich River: abandoned farm equipment from 1929, and an Eastern Skunk Cabbage emerging for spring

At home I find new challenges, especially living and working with just one other person 24 hours a day (while worrying about the family that is further away who I cannot care for in the direct way that I am so used to doing). We have implemented a new protocol in our household which we call the ‘North Atlantic Submarine Patrol Duty Rules.’ Whenever one of us is on the brink of being snippy, we say this out-loud, reminding ourselves that people know how to live together in a confined space (under water no less) for up to three months at a time. You have to work it out. There is no alternative. And it makes us laugh, every time.

Finally, I want to share two observations I made yesterday while taking a (socially distant) walk in the most amazing local resource for us, the Reading Town Forest, established in 1930 in response to the catastrophic drop in the value of farm land along the Ipswich River following the Crash of ’29 and the start of the Great Depression. Town citizens, with very long visions indeed, planted trees on then worthless land so that they would mature in time for the benefit of future generations, aka me.

While walking, I took the two pictures above. One is of Eastern Skunk Cabbage sprouts just emerging for spring in the swampy bottom land near the river. The other is a piece of rusted old farm equipment along the waters edge, surely abandoned in 1929 and not moved since. They seemed to me the perfect juxtaposition of that which is lost in calamity, with that which might be born out of it.

I hope that you are finding new life of some kind in this moment of calamity.

Yours,

Anne

"Humans make tools, and we build structures and organizations, all to make our lives easier and more ordered in the face of physical and natural challenges. But we also face limitations, and we cannot control everything that happens to us. This is the contradiction we live with all the time."

Dear Concourse,

We have scattered, and many of us are also now shut in our homes or other places of temporary residence. I write first and foremost to say that it is our fervent hope that you are all someplace settled and safe.

As you find your new routines in the days ahead we are looking forward to hearing your stories, whether funny, ironic, frustrated, or unexpectedly joyful! This is an extraordinary moment in time, presenting global challenges that are both new in their particulars, and yet not new at all in their disruption of society.

As an historian, I know full well that the dislocation of people from their homes, often accompanied by stringent restrictions on their mobility as well, is a recurring feature of our collective life. So too is facing uncertain outcomes with forces we do not fully understand, whether they be at the microbe scale or the cosmic scale. Communities have faced our current stress before and found ways to cope, and even emerge with new ideas and new ways of doing things.

I offer you but one small example from the Amsterdam Municipal Orphanage (founded in the 16th century) whose records I have studied in detail. In the registers that documented newly arriving children, a notation was made next to every name of the following: 'kinderziekte gehad’ (already had the children’s illnesses, namely smallpox and measles — or not, if that was the case). They kept these records so carefully because although they could neither prevent or well treat those diseases, they knew that if they kept the proportion of previously unexposed children to a certain low level, they could better ensure the health of the whole community.

They used their powers of observation and analysis to find a solution to a terrible problem — not the solution we rely on today, but better than despair or doing nothing.

Humans make tools, and we build structures and organizations, all to make our lives easier and more ordered in the face of physical and natural challenges. We achieve amazing things as you know from spending time at MIT. But we also face limitations, and we cannot control everything that happens to us, despite our desire to do so and our sometimes hubris otherwise. This is the contradiction we live with all the time. I suspect many of you have new worries you did not have just a few weeks ago.

"What to do? First, embrace the worry. There is much to be legitimately concerned about. But this is also a moment to reflect on what you may be called to do, whether it is to help each other, support your family members, serve your community of relocation, explore new intellectual pursuits or home-bound hobbies, and find joy in every day."

I share your situation. My children and parents are far away, and one son and his wife are on the front lines every day, as a nurse and a public defender. My worry for them is sometimes so great it feels paralyzing. But I know that they both feel called to serve the people who need them even more than usual now. They are where they should be, doing what they should be doing. So what to do?

First, embrace the worry. There is much to be legitimately concerned about so this is not a bug, but a feature. But this is also a moment to reflect on what you may be called to do, whether it is to help each other, support your family members, serve your community of relocation, explore new intellectual pursuits or home-bound hobbies, and find joy in every day!

Several students are working now to devise a forum for all of us to share and hopefully archive what everyone is doing. We spent the Fall semester with the first-year group finding ways to explore across the greater Boston intellectual community. This spring we embark on a very different kind of exploration. We should be thoughtful about it, and share with each other, just as you did in your lightning talks last fall. Stay tuned for more on that.

Turning lawn into native wildflower garden

To get us started, I am trying to manage my own worries by doing some work in my yard. I’ve begun with an edge wall which will allow me to convert a big part of my lawn to a native wildflower garden (hopefully without upsetting my neighbor’s lawn). I want to engage in a bit of ‘wilding’ to restore some habitat for insects and birds. So here is that contradiction again — I build a wall (such a human structure) as part of an effort to let the ‘natural' back in. I urge you to explore your own contradictions. And to tell us about them.

We all wish you well in your new location, and long for the day when we can be together again in person.

Anne,

on behalf of the whole Concourse team

My message for today: to somehow keep a sense of humor about this crazy project we call life.

Hello Everyone,

I hope that this message finds you deep into some (at home) activity that mimics in some way a ‘spring break’ — or perhaps you find yourself thinking you need a break from this spring! Either way, my message for today is to somehow keep a sense of humor about this crazy project we call life.

We will soon resume the semester in a new way, where I hope humor will continue to abound, along with all the other features of our common life together.

My efforts to keep myself laughing were given a great boost last week inadvertently by our neighbor’s son (10 years old and a bit at loose ends with no school). On Wednesday the 18th I had delivered to the back of our driveway 6 yards of organic mulch for my garden conversion project. For those of you who don’t know your soil volumes, 6 yards is a whole heck of a lot of mulch.

The next day my neighbor texted to say that her son, who has been struggling with his daily remote writing assignment for school, chose our mulch pile to write about as something new he had observed. We laughed so hard at the thought of a desperate 10 year old reduced to writing about a mulch pile. But then we got inspired to make a joke out of it.

So early the next morning we put up a Good Morning sign for him. I’m not sure what Simon thought about all of this, but his parents sure enjoyed it. And I was off and running….

The following morning we put out our garden friends, Shaun and Timmy the Sheep:

And then it got cold — a dip back below freezing — so the next morning we prepared our friends with hats for the weather. Well, you get the idea. Every morning we have come up with something, including an "avalanche risk" sign.

What might not be apparent is that the mulch pile is getting smaller, somewhat every day. And now that my creativity has been taxed for a week I have every incentive to get all of the mulch out in the yard where it belongs so that Simon can find something else in the immediate neighborhood to write about for school.

I hope there is a mulch pile to laugh about in your life!

Yours,

Anne

On behalf of the whole Concourse Crew

May you all find a new friend in these strange and complicated times!

Good Morning Concourse,

Welcome back to the Spring Semester ’20. I hope you are looking forward to getting back into the swing (or some variation on the swing anyway) of things. I know I speak for all of the Concourse staff when I say that the past two weeks have been overfull of learning how to make new arrangements, but also missing all of you. So it will be great for us to “see” you again in the next days ahead.

Now that the official break has come to a close I wanted to wrap up the saga of our mulch pile and our neighbor’s son. It has had an unexpectedly happy ending from my point of view.

As you saw from an earlier posting, we put out a new ‘message’ to Simon on our mulch pile every morning for a week. On Friday, the 8th day, I hoisted the flag of surrender:

Not only was I out of ideas, but the mulch pile was slowing making its way one wheelbarrow load at a time to the new garden taking shape.

Then, on Saturday, our neighbors got the final word while we were out in the middle of the day doing a bit of shopping. They waited until our car pulled out of the driveway, and then they pounced. Here was their contribution:

But the best part of this story is that I now have a new friend in Simon. In the two years that we have lived here, Simon has been too shy to actually talk to us (other than the quiet hellos his parents insist on). But on Saturday afternoon while I was out in the yard moving mulch Simon negotiated with me (with proper physical distancing of course) for some employment.

He offered to pick maple seedlings in my yard and gardens for 3 cents a seedling, as he does in his family yard. As some of you may be aware the Norway Maple (a prolific invasive and very common street tree in New England) produces thousands of seedlings every spring to the menace of all other gardening.

Simon has big plans for Legos he wants to purchase. I have big plans for not picking thousands of nuisance seedlings — a perfect match!

So, signing off from Spring Break and hoping you all find a new friend in these strange and complicated times!

Yours,

Anne

"Last week my focus was on keeping a sense of humor in the face of new restrictions. Today I find myself reflecting on the need to cultivate patience, a much heavier lift for me."

Good Morning Concourse,

Last week my focus was on keeping a sense of humor in the face of new restrictions. Today I find myself reflecting on the need to cultivate patience, a much heavier lift for me.

I have a dear friend who is a naturalist educator, a specialist in vernal pools and their creatures and my long-time tent partner on Scouting trips with our sons: steadfast and solid as a rock in every way. In early March she developed a ‘mild' case of coronavirus, likely from exposure to one of her students, an asymptomatic child of a BioGen conference attendee who had the virus.

She and her husband immediately quarantined themselves to the house to wait it out. Her cough has been so wrenching that she has not been able to speak on the phone since the first week home, and many days her headaches prevented her from looking at a screen. So my ability to communicate with her regularly was cut off, with only sporadic text updates to assuage my worry. As things worsened she was put on an inhaler, and my anxiety grew. She was so close and yet impossibly far away, and there seemed nothing I could do for her at all.

In a moment of desperation two weeks ago, I found a get-well card I had saved up, wrote her a note, and posted it in the mail. And as long as I was doing that, who else might I send an old-fashioned card to? — local elderly friends I cannot risk visiting, old family friends I usually only write to for the holidays, even my own parents just for the fun of something different than my daily phone call. Since then I’ve made a walk to the post box every other day, shooting messages of connection off into what seems like a void.

Having become so accustomed to near instant feedback for everything, this has been a real exercise of faith for me. Finally, on Tuesday afternoon I received a text from her thanking me for the cards, and saying that although she was still coughing, she was improving. Reading the short text, I realized that I was spontaneously in tears, crying from the relief of knowing that what had loomed in my mind as downward spiral was slowing turning into upward recovery.

Before I close, let me tell you something else about this friend. On a rather-more-dramatic-than-one-would-like two-week backpacking trip to the Philmont Scout Ranch a decade ago, the two of us, along with 3 scouts, were trapped at the edge of a meadow in a sudden thunderstorm. In an unrelated incident I had fractured my wrist only that morning (long story, involving succumbing to bravado and peer pressure).

So there we were, crouched on the ground in lightning position under torrential skies counting the seconds between lightning strikes and their accompanying thunder, and trying to keep up the spirits of the boys in our charge. The 40 terrifying minutes it took for the storm to pass fully overhead were the longest of my life. At a moment when you most wanted to huddle with other people, you had to be spread far apart, another kind of 'social distancing’ to protect the safety of the group.

Climbing Mt. Baldy; the lightning position

"The 40 minutes it took for the storm to pass fully overhead were the longest of my life. At a moment when you most wanted to huddle with other people, you had to be spread far apart, another kind of 'social distancing’ to protect the safety of the group."

One last thought about communicating into the void. I taught my first zoom ‘lecture’ this week, finding it disorienting to speak to a group of students whose learning needs I cannot assess as I can when we are all in the same room together: my message now disconnected from their reception. This is perhaps not so different from dropping those cards into the mailbox. I have to muster faith to keep teaching, and to be patient waiting for the response.

Hoping you find new patience in the days ahead. Signing off to take my rainy walk to a post box.

Yours,

Anne

"In this week which holds ritual significance for many around the world, I hope that there is a small miracle waiting for you somewhere unexpected."

Dear Concourse,

As we enter into the start of our fourth week at home the reality of a long wait is beginning to sink in. Many aspects of my daily life which I take entirely for granted are increasingly coming into sharper focus. This is also a major holiday week for Jews and Christians around the world. The juxtaposition of religious holidays — usually so vibrant with family and friends -- with widespread solitude is definitely worth a pause for reflection.

When I was growing up my Mother (once I knew it was not Santa, that is!) always put an orange at the bottom of our Christmas stockings, right down at the toe. It was meant to be the very special sweet treat that you uncovered once you had gotten through the socks, pencils, erasers, toothpaste, and other entirely utilitarian “gifts” that were the stuff of our stockings. An orange had been the treat of her own childhood, marked by the privations of the Great Depression and World War. Of course, my brother and I were not terribly impressed by an ordinary orange and would promptly return them to the fruit bowl in the kitchen. While I retained the practice of utilitarian stocking “gifts” for my own children, I did replace the orange at the toe with a small bag of chocolates. These they promptly devoured, often in lieu of a real breakfast.

Gifts are a funny thing. We await them with much anticipation but so often they don’t satisfy. On Saturday I was reminded of this phenomenon by an exchange that was never intended to be about gifts, but ended up feeling like one. My teaching partner in the Medieval Economy course, Ellan, had a computer accessory that needed to be passed along to me. I planned to pass along to her my old sewing machine with the broken bobbin winder since having a machine that sewed at all was better than none, and I could fill a variety of bobbins in different colors of thread on my new machine to send along. I would drive to Cambridge and meet her in front of her place, allowing a swap without physical contact.

As we made our plans, the list of items to exchange grew. I was making sourdough bread: did she need a loaf (touched only with gloves before being wrapped)? She had compost in her freezer saved up for my garden project. Even better, she had flattened cardboard boxes for suppressing grass under the mulch. She also had some spent daffodil blooms, but nowhere to plant the bulbs for next year. I assembled a bag of fabric scraps, a few bigger lengths of fabric (including a piece of silk I had been saving for a ‘special occasion’), and other odd bits to facilitate sewing. Careful planning and precision timing allowed for a very efficient exchange: the Great Sewing Machine-Cardboard & Compost Swap of 2020. Later that afternoon, Ellan sent me a text saying that it 'felt just like Christmas.’ She was exactly right.

Ellan and Anne during the Great Sewing Machine-Cardboard & Compost Swap of 2020

All of this brings me back to those oranges.

Long ago in December, when the flu season seemed like it would be an especially difficult one, my husband and I began sharing an orange every evening as the last snack before bed — for the extra vitamin C we joked to ourselves. As flu humor morphed into virus anxiety, and we began our life working at home together, we took to sharing an orange in the morning too. The two daily oranges (thanks to the large box on sale at Costco) have become for us a genuine treat, sweet and communal both.

I am definitely going to revert to my Mother’s practice of putting an orange at the toe of our family Christmas stockings, to serve as a yearly reminder of the small miracle that is a fresh orange, and that the best gifts are usually the ones we are not looking for.

In this week which holds ritual significance for many around the world, I hope that there is a small miracle waiting for you somewhere unexpected.

Best,

Anne

"I’ve been thinking a lot this week about the ways in which good things have to be nurtured, often for very long periods of time before we can see results."

Good Morning Concourse,

It seems unlikely that the sun is going to make much of a breakthrough here in Boston today, but I’m determined to hold onto the adage that ‘April showers bring May flowers.’ So whether you are in sun as you read this, drizzle, or snow, I hope something good is being nurtured by the circumstances of today.

I’ve been thinking a lot this week about the ways in which good things have to be nurtured, often for very long periods of time before we can see results. We wait impatiently (or at least I do) for treatments, antibody tests, and vaccines to address our current global crisis. When we are waiting for something to come to pass days can seem like weeks, which in turn can seem like months. But I know from experience that when we look back from a more distant vantage point, we won’t be able to figure out where the time went, it will have raced past so quickly.

Some years ago when my older son Thomas was late in high school we had an (extended) period where we were at odds with each other about everything. Conversations were fraught, advice unwelcome (in both directions), and conflict was ever at the ready. But somehow in all of that we kept talking to each other nonetheless. One activity we managed to do together pretty regularly was the very late night walk of our family dog, Zorro, a massive Black Lab-Newfoundland mix (or so we surmised from his features).

The rest of the household would be safely asleep, but I worked very late in those years and Thomas refused to go to bed as some teens are wont to do. We had the world to ourselves and could talk/argue all we wanted on an endless variety of subjects. As I remember it, Thomas regularly made all sorts of pronouncements about the world, and I would ask probing questions to poke holes in those pronouncements. (I suspect he remembers this differently!) One night, arguing about some subject now long forgotten, he stopped and turned to me saying: “Mom! You have no idea how exasperating it is to have a social scientist for a Mother!”

So I stopped too, right there in the middle of the street, in the middle of the night, and laughed so hard I thought I was going to die. He of course, having scored his major point, could not understand why I thought this was so funny. But he was right in a way that he could not have known then, but surely does now: It is exasperating to be a social scientist, and to spend your days and nights probing the fault lines of society, worrying over its problems, keeping track of the trade-offs between competing values, and trying to assess evidence in a sea of noise. I’ve been feeling the weight of that burden a great deal this week as I pore over current data, as well as the historical data generated in the wake of the great 14th century pandemic of bubonic plague which was the subject of our medieval economy course lecture this week.

L: Thomas and Tyler; R: Zorro in the park

Thomas, as I have mentioned before, works as a Public Defender in Augusta, GA. His wife, Tyler, is a Med-surg nurse supervisor. They were both sent home from work last Friday afternoon after she presented with a fever and was tested for the virus, and Thomas was developing a cough. It was a long weekend of waiting for her results, which they sensibly spent sleeping. When word came back on Monday afternoon of a negative result, and her fever was gone, they both reported back to work on Tuesday, business as usual. Who knows what the true situation is; and of course they continue to do everything possible under the circumstances to protect others as well as themselves.

The hospitals and prisons are both full of people who need experts to care for them and to advocate for them. And to do both of those things with kindness. I’m glad they had a long weekend of rest, but they are glad to be back doing their part to instill some order in a chaotic world. Thomas has become the social scientist he so resented me for being — devouring data in the news, texting me regularly with policy analysis updates, asking for a paper subscription to The Economist for his birthday. It took a lot of rain between us (along with some excellent sunshine from Dad) to nurture that seed. But now I can see it grown, and in action in the world. It was worth the wait, that is for sure.

Plant a seed this week. Nurture it faithfully. Be patient for the long-run, even while being restless for the moment.

Yours,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Associations

"I reminded myself that we can only ‘take heart’ if there might be reason not to. If everything goes only the way we want it to, we need neither hope nor heart. They are born in hardship and loss, not in contentment."

Good Evening Concourse,

Today began for me with an email from an Italian colleague and friend who had intended to spend the first part of April at MIT as part of our MISTI-Italy collaboration. Instead, we have been keeping connected with her via email and video conferencing as first her region went into lockdown followed by ours. Her email said simply: "this is the first Easter at home…let’s hope the last one.”

In this new life we live primarily on our computers at home, reading email was followed by “attending” an Easter service broadcast joyously, but from a mostly empty sanctuary, one that would normally be so full that extra services would be required. The message of the day was to "Take Heart" despite the troubles we must face in the world. There seems no shortage of those at the moment. My imagination is overfull with them, and it is difficult to get them to quiet down. But of course, those troubles were actually there all along. I was just paying less attention.

The digital holiday continued with the ‘passing of the peace’ via text. Then there were FaceTime calls with our kids, and parents. And more texts from siblings, nieces, nephews, and friends. Even the bunny rabbits this year were internet memes, complete with face masks. All heartfelt, all deeply appreciated, and all somehow not quite enough. Where in this world of zeros and ones is there a place for real society? And how cruel it is that the most pro-social act we can perform is to be anti-social, to cross the street away from rather than towards, to attend without going anywhere. In an effort to preserve life, we have shuttered it.

But that is no way to end a day marked for millennia as a celebration of new life. So I went back to my first email of the day and read again, ‘let’s hope.’ I reminded myself that we can only ‘take heart’ if there might be reason not to. If everything goes only the way we want it to, we need neither hope nor heart. They are born in hardship and loss, not in contentment.

Hope and heart are indeed hard-earned gifts. But they are truly gifts nonetheless.

Yours,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"The capacity to live with oneself in quietude is needed now as never before in my lifetime. For those of us for whom that does not come naturally, we clearly need to cultivate it. So I have turned my attention to upping my game for solitude."

Good Morning Concourse,

As I write to you this morning, light snow is falling out the window. It is not serious enough to stick on the pavement, but the planter boxes with my early peas and salad greens are now dusted white between the green shoots. It has definitely been an odd spring!

As I am sure you have observed in your own lives, some people truly thrive on the energy they pick up from being in thick company, and others have a preference for the laser-focus they can maintain if not socially distracted. In our family we split the difference. I fall most often into the first category and my husband into the latter. So on Monday evening when he announced at dinner that he was really starting to miss the synergy of working with his team in the office rather than as rectangles on a screen, I knew it was time to give some serious thought to the problem of solitude.

In an oft-quoted passage from his Pensées, Blaise Pascal claimed that, “All of man’s misfortune comes from one thing, which is not knowing how to sit quietly in a room.” It is possible that he is onto something, but I’ve never been convinced. While I concede the narrow point that if everyone truly were content to sit quietly on their own, there would be a lot less conflict in the world. But a whole lot less would be accomplished in the world too. The great human misfortune, it seems to me, is actually our inability to work together without conflict. Just refusing to be with other people altogether, or perhaps not even desiring companionship, seems hardly a solution we should promote widely. Cooperative togetherness, when it actually works, has left plenty of evidence to recommend itself.

But here we are, beginning our second month of what I am starting to think of as togetherness-deprivation. The capacity to live with oneself in quietude is needed now as never before in my lifetime. For those of us for whom that does not come naturally, we clearly need to cultivate it, just as with any other skill from which we would benefit but don’t yet possess. So I have turned my attention to upping my game for solitude.

The member of our family who has really mastered this is our younger son James (pictured below running on the beach in SoCal in February, in between our niece's wedding ceremony and the reception).

James McCants, running on the beach in SoCal, after a family wedding ceremony

By choice, he runs ultra marathons — meaning he actually enters lotteries to join and then pays money, all for the privilege of what seems to me like a form of deliberate sustained suffering. Yet, he assures me that physical limitations are not actually the main obstacle to completion, but rather being at peace in your own head. Indeed, the joy of running for 50, 70 or 100 kilometers in a go is precisely the space it opens up for deep communion with yourself. It offers time to think without consciously thinking. On the trail one can sort out what is important, what not; assess priorities without distraction; and be truly oneself. When I push him further though on the question of loneliness, the answer is surprising.

It turns out that the people who run these races are members of a profoundly connected community. They watch out for runners in distress. They support each other. They share snacks, tips about socks, shoes, training, but also life stories, all in passing. James says that a highlight is finding someone older, with more experience behind them, to run alongside for a spell, and learn from. All to say, ultra marathoning is not in fact anything like sitting quietly in a room. Rather it is a blend of being quiet with oneself and finding synergy in society.

I think my model for going forward into this next month needs to draw not from Pascal but from the example of James' dog, Dakota. Here she sits quietly in her room as required by the current state of affairs. But she very much has her eyes on the world, eager to rejoin it as soon as possible. What she has learned about herself in the process, one can only guess!

Hoping you are learning new ways to find contentment in solitude, and discovering new insights about yourself, but with the goal of taking those skills and insights back into society when we can again be cooperatively together.

Yours,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"The winds in our lives have shifted, in ways it did not occur to us to imagine. We will need entirely new strategies to navigate these winds, especially during the long periods in which we are becalmed and it feels like there is no momentum.

Have your destination clearly in mind, and even when your progress is so slow as to be imperceptible, continue to work your way towards it. Long off-shore races are won at night!"

Good Morning Concourse,

Happy Patriot’s Day! It’s perfect marathon weather today in Boston -- partly cloudy, cool but not cold, and little wind. But the only marathon going is the one the whole world is on.

As many of you know, our Continuing Conversations seminar this semester is reading selections from the Essays of Montaigne. Last Friday we tackled 'Of the Inconsistency of our Actions,' a reflection on “irresolution” which Montaigne asserts at the outset "seems … the most common and apparent defect of our nature;” or to put it another way, that “there is as much difference between us and ourselves as between us and others.”

A facile reading here might suggest that our goal should be to avoid altering our behavior or changing our minds about anything. But for a man as devoted to the benefits of education as Montaigne was, this would make little sense. Clearly, at this moment in our own lives we have all altered our behavior radically, and appropriately so. New information requires new strategies and new approaches. Even so, constancy in a person is a thing much to be desired, perhaps even the “principal goal of wisdom” as Montaigne asserts.

For as long as I've known him, my husband Bill, who grew up in Southern California in a sailing family, has said that “long off-shore races are won at night.” Why?

Because there is very little wind overnight off that coast and every hint of it has to be worked to its fullest potential. I learned the true meaning of this inadvertently one beautiful summer weekend on a trip we took together to Catalina Island with the intention of seeing some parts of the island not easily accessible by land.

We lingered into the mid-afternoon exploring nooks and crannies, knowing that we had the off-board motor as a backup for the return to Long Beach harbor if the wind died down before we completed the 26 mile crossing. But as luck would have it, this was the trip during which the motor board finally gave way to rot, and not far off the coast of Catalina the motor sought its final resting place at the bottom of the sea. (I should also say that Bill is wonderfully fastidious about maintenance of everything to this day. His father, whose boat we were using that day, was not.)

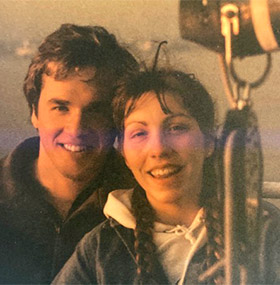

Anne and Bill, sailing in the early 1980s; Bill, sailing more recently

As evening came on the wind died to almost nothing, just as it did nearly every summer evening. We settled in, not much less safe than one ever is out on the ocean, to enjoy the long, slow ride home. To remain calm in heavy winds is impressive to be sure; but to remain both calm and steady in almost no wind is even more so; and to dock a boat in its proper slip in a crowded harbor with almost no power behind you is a feat of incredible skill and patience, something Bill finally did somewhere around 1 or 2 am. That was the night I decided for myself that I was going to marry this guy. As you can see in the photos above, we wear better sun protection these days than we did in the early 1980s, but otherwise the qualities of the overnight sailor have been the qualities of the partnership.

Back to Montaigne for a moment before I sign off. It is possible to resolve his paradox of lauding consistency while promoting the acquisition of new information. “Our plans go astray because they have no direction and no aim. No wind works for the man who has no port of destination."

The winds in our lives have shifted, in ways it did not occur to us to imagine. We will need entirely new strategies to navigate these winds, especially during the long periods in which we are becalmed and it feels like there is no momentum. Have your destination clearly in mind, and even when your progress is so slow as to be imperceptible, continue to work your way towards it. Long off-shore races are won at night!

Yours,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"Today is just the day to start your own Earth Day project, however small it may seem, one wheelbarrow full at a time!"

Dear Concourse,

Greetings from a beautiful day in Boston where the sun is finally showing the appearance of April even if the solid ice in my bird bath this morning did not.

It has been some time since I wrote to you about my lawn-to-garden conversion project where slow but steady progress has been made. You may recall the 6 yards of mulch that I had delivered the first week we were all away from MIT and that my young neighbor found so intriguing, at least in the absence of genuinely interesting things once schools and playgrounds had been closed.

Well, this past Tuesday the last shovelful of mulch found its way from my driveway to a proper home in the yard. If you have been keeping track of time passing this spring that is 5 full weeks, more than enough time for Simon to figure out that mulch really is pretty boring and perhaps not really worth writing about. Still, I feel a great sense of accomplishment, a scarce and most welcome sensation, and I cannot resist writing one more time about that mulch.

If you have been living in the Northeast for the past month, or reading the not-so-suble hints of my frequent weather laments in these missives, you know that it has been a very wet spring. I stopped adding up the precipitation totals from my own rain gauge about a week ago once we crossed the 6-inch mark since the mulch delivery, admittedly not the calendar delimiter that the National Weather Service uses for their historical record-keeping.

But even the NWS tells me that nearly half of the days in April so far have had precipitation of some kind, including hail and snow. This has made working in the yard more challenging, not least because 6 yards of mulch under the best of circumstances weighs about 4,500 pounds, and super-saturated with rain about twice that. When I think about it that way, my 5-week effort — one wheelbarrow full at a time — no longer feels so anemic.

I’m also very excited about the outcome to date. Approximately 850 sq. ft. of lawn have been covered, first with cardboard, and then mulch, opening up space for several hundred bee- and-bird-attracting wildflowers that will go in next month after the cardboard has had more time (and hopefully rain!) to rot; our peach tree sapling is no longer awkwardly surrounded by a sea of grass; future lawn mowing has been cut in half; a low wall now delimits the boundary between garden and lawn; and a new footpath leads to the gate into the backyard.

Apropos of President Reif’s Earth Day manifesto yesterday in The Boston Globe calling for among other things making our society more equitable and resilient, I want to do my small part to make my neighborhood more climate resilient and hospitable to the flora and fauna that were here before I moved in. Helping my neighbors to “recycle” some of their cardboard shipping boxes in the process feels even better.

I hope that there are some peach blossoms (even if yet tiny) and daffodils in your line of sight today. But don’t overlook in their splendor that which is less visible, like the insects that pollinate those blossoms and the wonderful process of rot which makes new life out of old. Today is just the day to start your own Earth Day project, however small it may seem, one wheelbarrow full at a time!

Yours,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"Montaigne does not stop there, however, with only our vices and those fundamental conditions. His goal is to not settle for the merely useful, but to strive for the honorable, in which he includes "friendship, private obligations, our word, and kinship" among other virtues."

Good evening Concourse,

Greetings from another soggy day in New England — or as I now think of it, another rotty day. I know the process of decay has to be at work in the yard because I have a delightful eukaryotic organism (known colloquially as slime mold) growing under my rose bushes on some newly spread mulch. If the bacteria and fungi necessary for growing the mold are present in the surface mulch then they must also be at work on the yard conversion sections too. It may not be pretty to look at, but the underlying process is rather amazing in its own way.

As I've noted previously, we are reading the Essays of Montaigne in our Continuing Conversations seminar. What a blessing it has turned out to be for this term to settle in with such a perceptive and quirky guide to a life of isolated reflection, in his case one chosen deliberately. Prof. Rabieh and I had at first considered Boccaccio's Decameron as our reading choice for the term, but now in hindsight I'm rather relieved that we are not working our way through a collection of bawdy tales framed by the specter of the Black Death. I do wonder though what it says about us that we landed on these two possibilities, for this spring in particular, both of which carry the whiff of quarantine about them?

In any event, Montaigne was the choice. As always there is something to learn, even when as today while reading in error a selection not actually planned for tomorrow's discussion. (In a classic move, I did the wrong homework!) I'm not sorry about it though, as the essay "Of the useful and the honorable" begins with a fantastic line: "No one is exempt from saying silly things. The misfortune is to say them with earnest effort." That has now made it into my commonplace book.

But despite his protests to the contrary, I'm not sure that what he goes on to say is actually so silly. He observes that "there is nothing useless in nature, not even uselessness itself. Nothing has made its way into this universe that does not hold a proper place in it. Even our 'sickly qualities' that we would easily be tempted to eradicate if possible, cannot be. Whoever should remove the seeds of these qualities from man would destroy the fundamental conditions of our life." I've been stewing on this much of the day. Is it true, that we cannot remove the vices without altering the whole project? Does this pertain only to the flaws in our characters, where his examples are focused, or to nature in its fullest extent?

And from there I got to thinking about the birds (and squirrels, chipmunks, etc.) that congregate in our backyard around the various feeders that we provision. The menagerie of creatures that arrive every day have become our constant companions in this period of being at home. I find their strategizing and their inter-species skirmishes endlessly diverting. But they are occasionally deadly as well. A Cooper's hawk knows about the feeders too, and when it shows up, the rest scatter. Nevertheless, I find the evidence of fur and feathers in the yard from time to time suggesting the hawk has hit its mark. This is surely one of the fundamental conditions of their lives.

Montaigne does not stop there, however, with only our vices and those fundamental conditions. His goal is to not settle for the merely useful, but to strive for the honorable, in which he includes "friendship, private obligations, our word, and kinship" among other virtues.

I must close this note, in part so I can get back to completing the reading I was supposed to have done. But as we tackle each day the tasks before us that are useful, those that arise from the very conditions of our lives, be sure not to neglect the honorable. Rot is good for what it is good for, but the prize is still beauty.

Yours,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History, and Director, Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"Just about everything worth doing in life takes time, and often enough nerves too. I hope that those of you who planted a seed of some kind a month or more ago now, are beginning to see some sign of things to come."

Good Morning Concourse,

It was a glorious weekend here in New England allowing people to emerge from their homes with what felt like a new lease on life. There were people sitting in lawn chairs on their driveways greeting passersby on the sidewalks; families going by on bicycles; neighbors talking over back fences; and lots of work going on in yards and gardens. You can guess where I spent more of my time than I had planned, to the detriment of my academic work if I’m being honest. But the lure of sun and warmth was too much to resist and everything needs its season.

After a month of rain I was hopeful that I could begin the first planting in my lawn conversion area. As I expected, my shovel broke through the soggy cardboard layer with ease, although the matted turf of decaying grass underneath still gave me a serious workout. I put in the first 42 plants of the several hundreds planned for over the course of the next two months as they become ground-ready.

I also have seeds that still need several more weeks of cold stratification in the fridge before they can go in the ground for what I hope will yield a whimsical mix of milkweeds, butterfly bushes, various wild indigos, and false indigo too, Joe Pye weed, lobelia, sneezeweed, Ohio spiderwort, blazing stars, sunflowers, coneflowers, goldenrods (tall and short), prairie coreopsis, golden alexanders, salvias, yarrows, and more.

Just writing the names out makes me incredibly happy as they are all so cheerful. I had thought that my patience would be tested waiting out the first phase of the project, but now I realize the real test is going to be the long process of filling in as the plants grow, each at their own pace. I will water faithfully, and fret of course, but they will take their own sweet time and I cannot rush them.

For now, they are thinly spaced as you can see with the first plugs of Blue Woolly Speedwell I planted to provide ground cover around the new pathway stones. By this time next year they should be sporting a glorious mat of small violet flowers. You can also see a stray tulip edging its way in front of the gate, I suspect its bulb slightly relocated by a helpful squirrel.

The really big achievement of the weekend for me though was not the onset of planting, but actually doing something I have never done before in my life. I picked up an earthworm, more than one actually, to relocate them — not just with a stick, but with my own hand. This may not seem like a big accomplishment, but despite my long and great appreciation for the engineering and fertilizing work they perform, I have always been startled by them (to understate the case) when I encounter them moving about in the soil.

My friend the naturalist educator I’ve told you about before will laugh when she reads this, but it is really true. I have successfully avoided having to pick up an earthworm, ever! But when I started digging out tufts of decayed grass from under decayed cardboard I displaced whole armies of them — the ground itself was practically in motion. It was alarming to say the least, if not also gratifying that they were so committed to my project. Once I steadied my nerves to confront the slithering mass, and reminded myself that I really did not want them to dry out stuck on top of the mulch rather than hard at work under the cardboard, I picked one up and moved it back to safety.

Then another, and another, and so on: not enthusiastically, but eventually without my heart racing. Who knows, maybe in another decade or two I might try to confront my fear of snakes!

Just about everything worth doing in life takes time, and often enough nerves too. I hope that those of you who planted a seed of some kind a month or more ago now, are beginning to see some sign of things to come. And if you haven’t done it yet, jump in. On our own, we cannot fix the many problems of the world that exceed our reach, and they are so many as to be easily overwhelming. But we can prepare ourselves to our part in collective solutions as they emerge. Practice on the small things — the earthworms as it were — so that you are ready for the big ones in time.

With best wishes,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"If you do find yourself up at 3 am, either at the back end of one day, or the front end of the next, treat yourself to an occasional look up at the stars."

Good Evening Concourse,

I can well imagine that this message finds you deep in end-of-the-semester work, with its peculiar combination of time moving far too slowly and also much too quickly. As with the last week of every other semester I cannot wait for it to conclude, and yet cannot imagine how everything will be finished. There is a reassuring sense of sameness in experiencing that usual paradox even in this most unusual semester.

That said, this week has been an especially strange one for me. I was originally scheduled to be in Lund, Sweden for a week-long university review panel. When academic events around the world began shutting down earlier this spring I figured this review would have to be postponed.

But the university decided to keep to their schedule, with all of the meetings hosted remotely. So without going anywhere at all (and missing out on all those lovely meals I had anticipated), I’ve nonetheless spent the week working in Central European Summer Time: seven hours of meetings each day, beginning at 3am EDT.

By the time my European colleagues were thinking about their suppers, the midday sun in Boston had me fully awake, and without an excuse to skip my afternoon MIT obligations: more or less jet lag without the jet. The alarm going off at 2:15 every morning has had even our dog, Katie, confused!

The situation in Sweden is, as I suspect you have seen in the news, rather different than here. While some of my colleagues logged in from their homes, others were in their offices to which they are permitted access, even though the university is not hosting in-person classes or events on campus. Seeing the familiar landscape of an academic office reminded me how much I miss mine.

What a privilege it is to have a small room full of books waiting for you every morning. I shall try to remember this several years from now when I’m tempted to go back to complaining about having to go to work.

The hour is late for writing, especially as I began my day in Sweden as it were, and you are likely pressed. But if you do find yourself up at 3, either at the back end of one day, or the front end of the next, treat yourself to an occasional look up at the stars. As I’ve been reminded all week, they are rather glorious at that hour when all else is so still, and the artificial lights are at their dimmest.

All best,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"To truly nurture something it is not enough to just keep it alive, but to see it multiply and bear fruit."

Good evening Concourse,

Today is marked in our collective calendar as Mother’s Day, a celebration that officially dates in the United States to 1908 when Anna Jarvis memorialized her mother’s many decades of activism for the peaceful resolution of national conflicts, a cause she took up while nursing soldiers on both sides of the American Civil War. The connections between nursing, nurturing, honoring, and the healing of divisions seems perfectly apposite for our current moment which cries out for healing of both bodies and the body politic. I hope that you have all taken the opportunity to honor someone today who has nurtured you.

Mother is also the colloquial name given to sourdough starters. Hence, part of my own Mother’s Day celebration today was to bake sourdough bread from the starter I developed in the fall of 1985 in the first year of my PhD program at Berkeley. Long about October of that year I decided that I needed to do something generative if I was going to survive graduate school. Little did I realize then that life after graduate school would continue to require regular restoration of body and soul if it was going to be survived.

I’ve been baking with that starter ever since, about three to five loaves of bread per week, when I’m not traveling anyway. I have never thought about it this way before but this must represent multiple thousands of loaves of bread over the intervening years. No wonder my sons in high school used to beg me to stop already with the sourdough bread. Why, they asked, couldn’t we just buy normal bread at the store “like everybody else!” Now, I’m happy to report, they pine away for the ‘real’ bread of home.

Bread starter is not the only thing I have carried about with me through successive relocations. I also have some cherished plants that have followed me from one garden to the next, having come to me in 2001 from the garden of friends when we moved to our first place with a yard -- one that was sadly devoid of anything more interesting than grass or invasive ground covers.

Despite what is now three moves and a year of sheltering in pots to avoid the ravages of construction scaffolding during an extended period of masonry work at Burton Conner during our tenure as Faculty Heads, my new garden is home to Solomon seal, columbine, wild geranium, dicentra, phlox, and pulmonaria (lungwort) all descended from that initial gift. Most of them are not in bloom yet this early in the spring, but the pulmonaria, which has multiplied from the one plant that survived the construction ordeal to a robust six, is in full flower.

The dicentra is also showing off as if all the rain of the last month had been some kind of ambrosia. Its distinctive flowers parade across the stems in a riot of pink, leaving no doubt as to how it acquired its popular name of 'bleeding hearts.’ Dicentra is toxic, especially when ingested but even slightly so to the touch. So just like the hearts in all of us, it has a capacity for great beauty and real harm simultaneously. Needless to say, the rabbits leave these plants alone.

In addition to blooms and bread, one other item of truly impressive longevity made an appearance in my life this past week. As I’ve told you before, I’ve engaged in a good deal of card mailing since we all folded ourselves into our homes in the middle of March. One friend from elementary school days has taken up the challenge and begun sending cards back — competitive card writing is a real thing in this world believe it or not! But she has won the prize definitively.

Yesterday in my mail, there was a message from her, written on a card from a box that had been given to her by our AP Literature teacher from our senior year in high school as a thank you gift for serving as a classroom assistant. Somehow despite the many peregrinations of her life since then she still had this box of cards in her possession. Reading the message, and holding the card in my hands, transported me back to a moment in time I had more or less forgotten about entirely. Yet the connecting threads were all still there, perfectly intact, indeed even having multiplied just like the starter and the plants.

To truly nurture something it is not enough to just keep it alive, but to see it multiply and bear fruit. Do honor those people in your life who have been like a mother to you, or perhaps are even your Mother. To be the fruit of their efforts is a great way to begin.

Wishing you all well,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"You too can be a superhero in so many ordinary ways. Embrace the cape and the red hat. And best wishes to all with finals."

Dear Concourse,

Congratulations on making it to the finish line of classes for the spring term! As I suspect was the case for many of you, I had been eagerly anticipating getting through the last of my class commitments ever since the tumultuous jump to online teaching in March. But as we gave our last salutes to the Friday Seminar and then Continuing Conversations last week, and again Tuesday evening to my Medieval Economy course, I surprised myself by feeling a deep sadness at the prospect of wrapping up and saying goodbye.

The Zoom experience is a far cry from the human experience; and yet, I feel a unique bond with this set of students after having shared such a dislocating experience together. We were cut short once already, and now it feels cut short again. I never cease to marvel at how we humans can feel relief and loss, joy and sadness, over the same event.

Whenever I find myself in that state of confused limbo between incommensurate oppositions, I turn to a long walk for clarity, or maybe even solace. Yesterday evening’s walk yielded another sighting of our neighborhood bunny messenger, now sporting a Superman cape as you can see below. I did not feel much like a superhero when I stopped to read, but I was willing to consider that it might be enough to just keep carrying on to earn the appellation.

On more reflection now this morning though, what I am really struck by is the ‘all’ which has been underlined on the chalkboard for emphasis. Those of you in the Friday Seminar this spring may recall that at our first session in early February we talked about ways of ‘Knowing and Discovering.’ I cautioned us then about the dangers of resorting to absolutes (best, least, every, none, etc.) in our analytical work. They lure us into making arguments we cannot sustain.

We are probably not all superheroes, even in times like these. There may be some villains among us, or perhaps more alarming, something villainous is possible in a great many of us. I think this is at least partly what Walt Whitman is trying to say in his poem Song of Myself, 51 when he writes, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” Of course we contradict ourselves; how could we not? Still, the ceramic bunny is a good reminder to dress ourselves up and play the superhero role in tandem with the others, and truly as often as possible.

The other new thing I encountered on this walk, limited as it is to the same several block radius immediately surrounding our home, was this fantastic little cluster of mushrooms making a spectacle of themselves in someone’s front lawn. Why there? Why all piled up on top of each other? What about the rest of the lawn that was mushroom-free? And where oh where was the little gnome in a red hat that was surely the perfect complement to this tableaux?

Although missing from the photo, the gnome is as vivid in my imagination as if it were there, and the thought of that picture makes me smile just as much as the superhero bunny does. So I make a small promise to myself that if I ever get so lucky as to have such mushrooms appear in my lawn I will make a small gnome to attend them. In fact, I should get going on that soon so that I am ready to pounce when opportunity knocks.

Friends, as you go into finals, don’t forget that you are large, you contain multitudes. You are engineers and scientists, readers and thinkers, musicians, artists, writers, poets, and orators. But you are so much more than your vocations and talents, formidable as those so often are. You are people, mired in the full complexity of being human. You too can be a superhero in so many ordinary ways, even while being a gnome in your imagination. Embrace the cape and the red hat. And best wishes to all with finals.

Yours,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"Despite the ferocity of the storm, the Bluets (Houstonia caerulea) were out in full force in the crevices in the granite boulders that form the shoreline."

Good evening Concourse,

This note comes to you in the middle of our finals period so brevity seems the order of the day. But encouragement would not be out of place either. So consider this a brief message of cheer to keep you striving toward your goals and holding your own against the winds that buffet us.

Friday night there was a sustained and torrential thunderstorm to the north of Boston. The lightning was close enough to jiggle our power, and the rain was so hard that at one point I found myself drawn to our kitchen window, only to discover my neighbors also standing at their kitchen door in equal amazement. A silent wave between us across the sea of water coming down on the driveway seemed a true embodiment of the expression, ‘we are all in this together.’

Saturday morning dawned bright and sunny, so my husband and I decided to venture northwards to Rockport to see the ocean after the storm. We took a short hike up the so-called 'Atlantic path' on the south side of the harbor until we were stopped by what were functionally ponds in the trail bed that had formed after the rain the night before. Despite the ferocity of the storm, however, the Bluets (Houstonia caerulea) were out in full force in the crevices in the granite boulders that form the shoreline.

This patch, a mere stone’s throw from the ledge over the ocean, showed absolutely no sign of being any the worse for wear. They are indeed small as this picture reveals, and appear to be as delicate as their popular name, Quaker-ladies, might suggest. But they are actually resilient and tenacious. So there you go. You may feel small, the rocks impenetrable, and the sea raging nearby, but hang on. But you too can be a bluet for finals week, and for life.

And when things really get rough, call in the fire dog! (As spotted in Rockport on the way to the Atlantic path.)

Here’s wishing you all well for these last few days of the spring semester of 2020, one for the memory books to be sure. Hang on in the wind, and put out the fires as they come.

Best,

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"No matter what comes, we will manage it better if we have been diligent in forming our character, sharpening our intellect, and broadening our horizon of inquiry, empathy, and experience."

Dear Concourse,

Whew! You made it to the end of the semester, bumps and all. All of us in Concourse offer our warmest congratulations for the greater than ordinary achievement this represents. Take a day or two off (or maybe you already have) before you tackle what’s next — a question weighing on many of our minds, whether this was your last semester at MIT as an undergraduate or you have years yet to go on that part of the journey.

I’ve been taking stock for myself the last few days, trying to wrap my head around what’s next for me too. Will we be able to see parents or kids this summer? What about friends less geographically remote? How should I plan for fall conference arrangements? What will teaching hold in store for us next year? How will we welcome a new cohort to our Concourse community? These and many more questions have no clear answers yet; and indeed, even when answers come, I suspect most of them will be beyond my control to influence. Of course, such questions never really have clear answers in advance. We just tell ourselves that they do. It is a critical protective mechanism for our daily lives, only upended on occasions when history intrudes in ways so dramatic that we must sit up and take notice.

Such thoughts always recall for me the poignant observations of a mid-20th c. English historian, Herbert Butterfield. Looking back in 1949 on the previously unimaginable (for him anyway, as a denizen of what he thought was a ‘civilized’ modern world) carnage of the First and Second World Wars, and the economic ruin of the Great Depression sandwiched in between, he struggled to make sense of it all, as an historian of course, but also as a human being. In an essay that I find myself returning to time and again, he has this to say about history:

“We might say that this human story is like a piece of orchestral music that we are playing over for the first time. In our presumption we may act as though we were the composer of the piece or try to bring out our own particular part as the leading one. But in reality I personally only see the part of, shall we say, the second clarinet, and of course even within the limits of that I never know what is coming after the page that now lies open before me.

None of us can know what the whole score amounts to except as far as we have already played it over together, and even so the meaning of a passage may not be clear all at once—just as the events of 1914 only begin to be seen in perspective in the 1940’s. If I am sure that B flat is the next note that I have to play I can never feel certain that it will not come with surprising implications until I have heard what the other people are going to play at the same moment. And no single person in the orchestra can have any idea when or where this piece of music is going to end.”

This observation puts paid to our hubris for certain. But it doesn’t mean we should stop practicing. That unknown orchestral score will be even harder to sight read if we don’t know how to play our given instrument to its fullest capacities. No matter what comes, we will manage it better if we have been diligent in forming our character, sharpening our intellect, and broadening our horizon of inquiry, empathy, and experience. And we have to plant seeds in hope as I have said so many times before in these reflections. I close by sharing with you the emerging fruits—well, vegetables and legumes really--of some of my spring seeds.

Please stay in touch with us this summer. Join us for zoom movies and discussion, or one of our several book groups, to sing and dance at our community party, or just for email chat. We are eager to hear what you find to explore, even if it is no further away than your own backyard!

With very best wishes to all, and a special word of congratulations to the Class of ’20!

Anne

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

PS. As you can see, my vegetable garden is strategically limited to pots on my porch. The next notes in the score to be played by the rabbits would otherwise be without doubt.

"[The seedlings] have much work ahead of them and many dangers to ward off. I will offer all the assistance I can, but the growing will be theirs: not so very different from how we send our graduates out into the world for their new beginnings."

Dear Concourse,

I write to you on the morning of MIT’s Commencement — a joyous day and a bittersweet one, perhaps especially this year since the physical departures from our campus community already took place under conditions of rapid unexpectedness. Normally we spend many weeks preparing ourselves for the impending departures of late May, time we did not have this year. Moreover, our world is in a state of flux, with many of us caught in a strange limbo between a host of problems that require urgent attention, and a daily routine characterized by limitation and slowness. How do we reconcile the many contradictions of our lives, especially on this day of marked by the extreme contradiction between joy and sorrow?

What really is this thing we call a Commencement? It is a ceremony of course, in which we confer degrees upon those who have completed a specified course of study, meeting its academic requirements with distinction and merit. But why in the world this particular word for such a ceremony? After all, the main definition of ‘commencement’ is (to quote from the Oxford English Dictionary):

1. The action or process of commencing; beginning; time of beginning.

How in the world did we end up with the gathering that marks so clearly the end of something, taking on a name which unequivocally means to begin? It might be that there is just no accounting for language, as we like to say about taste. But I don’t think this is actually the case. Rather, our academic celebration finds its roots not in the past accomplishments of those receiving degrees (as laudable as those are), but rather in the hopes we have for our graduates as they go out into a wider world and face its problems, as they take on new beginnings, and start new chapters of their lives. They commence in every sense of the word.

So on this day, let me update you on my own lawn-to-garden conversion project which I began at the start of our time at home. It began by building a wall to make the space, laying cardboard over the lawn to be repurposed, and then mulching over that. After a month and a half of rain and impatient waiting, the ground was more or less ready for plants when they were themselves ready for planting.

For the past three weeks I’ve been hunched over for a few hours in the cool of the morning almost every day putting in several hundred seedlings, one hole at a time. Now that they are all in, I feel tremendous relief and a sense of accomplishment, but also a sadness that I have no immediate job calling me back into the garden with gloves on hand. My project has graduated this week, with the to-do list crossed off and certificate of completion conferred. But it is also just commencing. As you see in the pictures below, those seedlings are small, widely spaced, and some of them especially vulnerable to rabbit nibbling (hence my box protection system supplemented by garlic and chili powder). They have much work ahead of them and many dangers to ward off. I will offer all the assistance I can, but the growing will be theirs: not so very different from how we send our graduates out into the world for their new beginnings.

So on this joyful day of Commencement, celebrate well! We who have walked with you this far remain in place to offer what assistance we can. But the growing is yours. This Commencement is truly your beginning.

Yours,

Anne

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association

"I can only exhort you not to stop at despair. Every small step you take to right a wrong, to help rather than harm, to show love rather than distain or worse hate, is a step for all of us."

Dear Concourse,

My idea of writing to you regularly this spring was part of an effort to keep us connected as a community after having to disperse so suddenly in March. I had not particularly thought I would continue to write into the summer proper. But yesterday in an email correspondence from a student who is working with me on a research project the closing read, “Pessimistic about the future, signature.” The subject of the email was not about the state of the world, public health, the governance of our nation, or our collective or even individual futures, all things we might legitimately be deeply concerned about. The email was about our scholarly project. Yet, there it was, impossible to ignore. How could we just carry on with our scholarly work when so much was amiss in the world, when so many losses had been sustained, and so many communities were suffering inconsolable grief? We could not; and so here I am writing to you again, to the community for which I feel a measure of responsibility for your wellbeing and your ability to carry on with the work of learning and serving.

I would not be honest with you if I did not admit that I often feel pessimistic about the future as well. So much loss, grief, anger, lack of leadership, and wanton disregard for human life, is hard to sustain, especially in the face of the environmental and viral challenges which were already ours to confront. And what can we do, actually do, about any of it? What difference does my condolence card make for the now multiple friends whose brothers have died in the last month? What difference does my small yard of pollinator friendly plants make to species in collapse? What does it matter if I bike to the Post Office instead of drive, or fully clean out my peanut butter jars for maximum recycling? What difference does it make if I vote, urge you to do the same, and compost my food scraps too? Does it matter whether we march in the streets, or stay at home and grieve? It all feels too small to counter the main trend. None of it seems enough.

But if this were all I had to say I should not be writing to you. Because you already know all this. You have seen the pictures endlessly repeated in the media and forwarded by friends, of relief lines stretching as far as one can see, of worry lines on the faces of medical personnel, of police lines telling people not to gather, protest, or mourn, or in a case of absence, the pictures of funerals without the lines of mourners who should be there to properly see off their loved ones and share their grief collectively. I have no pictures to send you today to add to these, or indeed to counter them.

Instead I can only exhort you not to stop at despair. Every small step you take to right a wrong, to help rather than harm, to show love rather than distain or worse hate, is a step for all of us. Each positive action you undertake is also a balm for your own soul, and you should not discount the value of that. In the late Middle Ages, especially post-plague, a discourse known as the ars moriendi emerged to teach people the ‘art of dying.’ To make a long story short, its most important insight was that the best way to ensure a good death was to have first lived a good life. And living well has nothing to do with the times you are given, but everything to do with what you do with them.

So what to do? I suggest--every day find ways to express inappropriate joy, engage in extravagant kindness, practice unmerited generosity. Be slow to judgment, giving your siblings, friends, parents, partners, and even strangers the benefit of the doubt. We will not always succeed, and we might not see any of it change the rest of the world in an obvious way. But if it changes you, you will have lived well.

I’ll sign off then, 'optimistic about the future you.’

Anne

Anne EC McCants

Professor of History & Director of the Concourse Program, MIT

President, International Economic History Association