THE MEANINGS OF MASKS

A collective cry for justice | Anthropologist Graham Jones

Today's cloth masks to minimize virus transmission reflect traditions of masks used in sacred rituals.

Photo by Miki Jourdan, Flickr

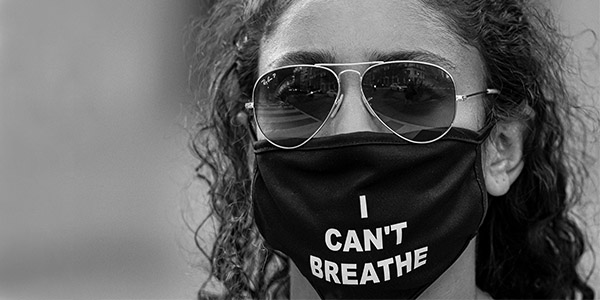

"For me the iconic image of our times is of Black Lives Matter protestors of every race wearing masks emblazoned with the dying words of George Floyd: 'I can’t breathe.' The use of the cloth mask as a substrate for a citational text situates the individual wearer as an actor in a broader social drama. Such protest masks are a creative, expressive way of subsuming one’s identity within a social movement — and one’s voice within a collective cry for justice."

— Graham M. Jones, Associate Professor of Anthropology

SERIES | THE MEANINGS OF MASKS

As The Washington Post has reported, "at the heart of the dismal US coronavirus response" is a "fraught relationship with masks." With this series of commentaries — inspired by ideas from Associate Professor of Literature Sandy Alexandre — MIT faculty explore the myriad historic, creative, and cultural meanings of masks, offering new ways to appreciate and practice protective masking — currently a primary way to contain the Covid-19 pandemic.

Graham M. Jones is a Associate Professor of anthropology and MacVicar Faculty Fellow at MIT. He is a cultural and linguistic anthropologist who explores how people use language and media to not only share knowledge, but also to imbue it with meaning and value. SHASS Communications spoke with him in late June 2020.

• • •

Q: Humans use masks for a variety of purposes, ranging from protection to play to ceremonial ritual and artful performances. What are some examples of masks and masking drawn from the field of anthropology?

A: The mask is one of the most important human artifacts in all of anthropology. It is a tool of transformation that allows its wearers to transcend themselves, taking on timeless roles in ritual dramas. Repositories of power, masks are sacred objects, crafted with ingenuity. My favorite ritual masks in the world are those created by the First Nations of North America’s Northwest Coast. Used in dances that tell stories of creation, some of the masks have faces that dramatically transform and change shape when properly used in performance. In this tradition and others, making and wearing masks is the prerogative of secret societies. Paradoxically, masks like these both disguise individual identity and signify membership in an exclusive group.

The surgical masks and cloth face coverings that most of us now wear for purely practical reasons may seem symbolically insipid in comparison to sacred masks used in ritual or performance. In practice, however, today's cloth masks have come to figure into everyday interaction rituals in ways that reflect central functions that anthropologists have long associated with masking: subsuming individual identities within culturally constructed personae and differentiating groups of people based on power and privilege. Like all masks, they are a medium of communication.

Kwakwaka'wakw mask transforms from a crow's head when closed to reveal a human face when open. Wikimedia

"The mask is a tool of transformation that allows its wearers to transcend themselves, taking on timeless roles in ritual dramas. My favorite ritual masks in the world are those created by the First Nations of North America’s Northwest Coast. Used in dances that tell stories of creation, some of the masks have faces that dramatically transform when properly used in performance."

Q: Given this cultural history, can you speculate on ways in which people today might explore the meanings and possibilities of masks that are needed for protection from the coronavirus?

A: For me the iconic image of our times is of Black Lives Matter protestors of every race wearing masks emblazoned with the dying words of George Floyd (as well as Eric Garner, Elijah McClain, and too many others): “I can’t breathe.” These masks represent a symbolic condensation of the two public health crises that define this moment in American history: Covid-19, a disease that kills indiscriminately by attacking the respiratory system, and racism — a disease whose violence is most brutally felt in the choking-to-death of individual Black people at the hands of police.

The use of the cloth mask as a substrate for citational text connects it to the function of the mask in the anthropological sense — situating the individual wearer as an actor in a broader social drama. Writing “I can’t breathe” on their cloth masks, protestors enact a symbolic connection between these two crises, seeming to ask why so many white Americans can readily upend their lives because of a respiratory infection when the deadly pandemic of state-sanctioned violence against people of color has festered unchecked for centuries. These protest masks are a creative, expressive way of subsuming one’s identity within a social movement — and one’s voice within a collective cry for justice.

L to R: Protest in Minneapolis, Minnesota, photo by Lorie Shaull; Surgeon wearing a medical mask, iStock

"Writing 'I can’t breathe' on their masks, protestors enact a symbolic connection between two crises, seeming to ask why so many white Americans can readily upend their lives because of a respiratory infection when the deadly 'pandemic' of state-sanctioned violence against people of color has festered unchecked for centuries."

Q: Many countries have adopted mask-wearing as a politically neutral health measure, but in the U.S., mask-wearing has been adopted more enthusiastically by liberals, while many conservatives have fought their use. What do you make of the political divide that has emerged in the U.S. about the wearing of masks for Covid protection?

A: The choice to mask or not to mask has become one of the most significant visible markers of social difference. People in Asia have long used cloth masks to prevent the spread of disease. Less familiar with this precedent, many Americans initially assumed that masks served to protect the wearer from infection. If that’s what you think, then wearing a mask is a conspicuous admission of vulnerability — particularly for those subscribing to ideals of toxic masculinity.

Even now that we should all know better, non-masking has become ensconced as a symbol of individualism (and denial of danger) and masking as a symbol of collectivism (and concern for the community in the face of peril). It’s truly astonishing that Americans have transformed a public health necessity into an ideological battleground of so-called virtue and vice signaling. This helps explain why the richest country in the world has one of the world’s highest rates of infection.

Early in the pandemic, Asian Americans feared wearing masks in public would make them targets of xenophobia, and African Americans feared masking would render them “suspicious” in the eyes of white people and their armed protectors. The ability to comfortably mask was a form of white privilege. Months later, the virus has disproportionately devasted Black communities — so much so that the nation’s top infectious disease expert has blamed structural racism for this impact.

Now the ability to comfortably not mask is a form of white privilege. This privilege became painfully clear when a white Arizona Republican used George Floyd’s dying words, “I can’t breathe,” to protest the mild discomfort he felt wearing a cloth mask — to the uproarious approval of a conservative crowd. This is the same kind of symbolic condensation I mentioned above, but in reverse: the mask is mobilized as a symbol of government overreach and a racist dog whistle for the asphyxiation of white supremacy. The refusal to mask becomes a way for far-right groups to exercise agency in crafting their own political personae.

Illustration of Graham Jones and one of his children by José-Luis Olivares, for MIT News Spotlight

"I am filled with gratitude for the bespoke masks my wife has sewn for our family. Those masks are a symbol of our family, and all she does to hold it together."

Q: What is the favorite mask you have ever worn, or seen someone else wear? Why did it appeal to you?

A: I am filled with gratitude for the bespoke masks my wife has sewn for our family. She let us each pick out fabrics from an online Etsy shop. One of my kids chose a Shiba Inu dog print, the other chose sushi (Japanophilia has been one of their imaginative outlets during lockdown). I just chose plain stripes, but my wife arranged them at jaunty angles. Those masks are a symbol of our family, and all she does to hold it together. We wore them when we went out to protest.

______

Graham M. Jones, an associate professor of anthropology and MacVicar Faculty Fellow, is a cultural and linguistic anthropologist who explores how people use language and media to not only share knowledge, but also to imbue it with meaning and value. In ethnographic engagements with many communities, Graham analyzes ways in which signifying practices shape our moral and epistemological convictions. He is currently investigating how language and culture shape, and are in turn shaped by, the way people use technologies of digital communication. His books include Trade of the Tricks: Inside the Magician's Craft (California, 2011) and Magic's Reason (Chicago, 2017).

Suggested links

Graham Jones: MIT webpage

MIT Anthropology

Book: A magician’s imperial mission

A new book by Graham Jones illuminates how magic became a tool for Western “reason” — and helped form the field of anthropology.

Class Profile: The Technology of Enchantment

In a new Anthropology + Studio Art maker class, MIT students investigate the human dimensions of interacting with technologies.

Class Profile: In search of a meaningful life

Popular MIT anthropology course offers contemplation and dialogue on life's big questions.

2019 MacVicar Faculty Fellows named

Professor Jones receives MIT's highest honor in undergraduate teaching

Anthropologist Graham Jones receives the 2013 Edgerton Award

For exceptional distinction in teaching and research

MIT Starr Forum

When Culture Meets Covid-19

The Washington Post

At the heart of dismal US coronavirus response: a fraught relationship with masks

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Series Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand

Editorial Consultant: Kathryn O'Neill

Publication: 2 July 2020