MEDIA AND THE PANDEMIC

CNN and Sesame Street team up on Town Halls for kids

MIT media scholar Heather Hendershot and children's literature scholar Marah Gubar discuss the programs which focus on both the pandemic and racism.

L to R: MIT Professors Heather Hendershot and Marah Gubar

"I'm interested in thinking about the town halls as media events and, more specifically, as political media events. Cable news is so polarized right now, and when you deal with kids and anything with political dimensions, it’s sort of inherently a hot potato situation."

— Heather Hendershot, Professor of Comparative Media Studies

INTRODUCTION

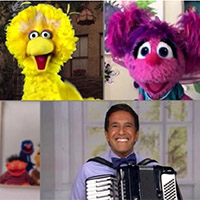

On April 25, 2020, CNN aired a coronavirus town hall, a one-hour TV special aimed at parents and children. The cable news network partnered with Sesame Street on the show, which was hosted by CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta and Erica Hill and featured Muppets such as Elmo, Big Bird, and Grover. On June 13 they continued the experiment with their ABC’s of COVID-19 town hall. In between, on June 6, CNN partnered with Sesame Street again on “Coming Together: Standing up to Racism.”

I recently invited Professor Marah Gubar to join me in a conversation about the Covid-19 specials, with the racism episode providing some additional context. Professor Gubar is on MIT’s Literature faculty and is the author of Artful Dodgers: Reconceiving the Golden Age of Children’s Literature, which won the Children’s Literature Association Book Award. More recently she wrote Seen and Heard: Remembering Children’s Art and Activism. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

— Heather Hendershot, MIT Professor of Comparative Media Studies

• • •

Hendershot: I thought we could open by explaining why we’re interested in the CNN–Sesame Street town hall specials on Covid-19. I’ll start by saying that, first, I'm interested in thinking about the town halls as media events and, more specifically, as political media events. Cable news is so polarized right now, and when you deal with kids and anything with political dimensions, it’s sort of inherently a hot potato situation, right? Children’s TV has never been an apolitical realm — lots of shows contain “pro-social” messaging about basic issues like how to share with others or be a good friend, or with issues such as valuing diversity or rejecting violence. That’s been the norm for entertainment shows since the 1970s.

But it’s obviously potentially more controversial to take on tough issues in a nonfiction context like the news. CNN was going out on a limb a little bit, and it could have backfired, but it didn’t. (CBS had similar success in the 1970s with news segments for kids run during Saturday morning cartoons.)

Second, I'm interested in the CNN town halls because although it’s not my research focus now, I started my career publishing research on children's media (especially network and cable TV), and I have an ongoing interest in the ways that adults imagine and construct an idealized child through their media creations.

Gubar: As someone who works in the interlinked fields of children’s literature and childhood studies, I’m interested in how adult ways of portraying and engaging with children have shifted over time and across cultures. So, I’m coming at it more from an interest in thinking about how Sesame Street and children’s television programs have changed over time. I think it’s really fascinating to compare the way Sesame Street functions today to what it was like in the '70s when the show first emerged.

Hendershot: I agree. It might be helpful for readers who don’t know about Sesame Street for us to fill them in. Sesame Street premiered in 1969 and was pretty radical at the time because it was taking seriously the goal of education, when the landscape of “educational” children’s television was pretty slim. Ding Dong School was a low-budget educational show where Miss Frances would demonstrate things like how to make a banana, lettuce, and mayonnaise sandwich. (I'm not making that up!)

And also, of course, there was the excellent Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, with an emotional focus. So on the one hand, Sesame Street was radical for doing serious curriculum development for three-to-five year olds, and on a really high budget, and on the other hand, it had a political agenda. The actress who played Susan even wrote her master’s thesis on the “hidden curriculum” of Sesame Street, about racial diversity and tolerance and picturing inner-city kids for the first time. They had a puppet who lived inside a garbage can! That might seem normal now but it was pretty crazy at the time.

"As someone who works in the interlinked fields of children’s literature and childhood studies, I’m interested in how adult ways of portraying and engaging with children have shifted over time and across cultures."

— Marah Gubar, Associate Professor of Literature

Gubar: When you go back and watch the early episodes of Sesame Street, it’s really striking how the street itself looks genuinely gritty, like a real city street, and the opening credits show kids in an obviously urban playground, like the one in Central Park where my nephews used to play. There’s something really powerful about those early episodes. And I love that Sesame Street was produced as a collaboration between academic experts in child development and psychology and people with commercial media experience like Joan Ganz Cooney, who also had an undergraduate background in education.

Plus, the show was influenced by the civil rights movement and MLK’s vision of a “beloved community” where poverty and prejudice aren’t tolerated. And it was partly publicly funded by government grants, to help level the playing field for disadvantaged kids who didn’t have access to preschool. It was so progressive.

Hendershot: Yes. And of course over time, as you know, the government funding has dried up and Sesame Street has become a politicized symbol of PBS. Today people don’t attack it so much for liberalism (though they did in the early days) but rather by saying, well, you don’t need the government to subsidize this because look at all the toys and DVDs they sell, so who needs federal funding for PBS? And now the show is on HBO Max, a subscription service, and kids can see the episodes for free on PBS nine months later.

So Sesame Street has adapted from the network era to the post-network, cable era. I think this is all helpful context for understanding what CNN is doing inviting Sesame Street to help them talk to parents and kids about Covid-19. It’s a landmark show on so many levels, and a strong partner for this kind of difficult programming. What are some of your immediate impressions of the CNN-Sesame Street town halls?

Gubar: My first impression is that I liked the Covid-19 specials more than the racism special, because the two Covid-19 specials did a better job incorporating Sesame Street’s already existing ethos. The whole idea that “we’re all in this together” and we need to take care of each other is such a core part of both Sesame Street and Mister Rogers, two shows that address the same question: “What does it mean to be a good neighbor?”

The ethos of neighborliness they promote has some religious overtones — Love thy neighbor — and also civic overtones about citizenship and democracy. I feel like the Covid specials really worked well with that, advancing the idea that when we take care of ourselves (wearing a mask, washing our hands) we’re also taking care of other people. This idea was so beautifully expressed in the song “Like Birds of a Feather. We're in this together.”

Hendershot: Yes! I loved that song too, featuring not only Elmo, Big Bird, and Abby Cadabby but also Sanjay Gupta on the accordion. I agree about the value of the informational material for kids, like how to make your own mask and how to wash your hands. Adults hear about those things all the time, but children might be picking up information in a more piecemeal way. It was also great to cut to a lot of kids asking questions.

For example, at one point in the first town hall a child asked about being safe and one of the adults answers, you know soap is for the outside but not for the inside and is really emphatic about never swallowing anything like soap. This is in some ways the closest that the Covid-19 town halls come to acknowledging the current political situation, don’t you think?

Gubar: Right — do not drink soap, detergent, or bleach. That should not have political resonance, but obviously it does at this moment.

"I liked the Covid-19 specials more than the racism special, because the two Covid specials did a better job incorporating Sesame Street’s already existing ethos. The whole idea that 'we’re all in this together' and we need to take care of each other is a core part of both Sesame Street and Mister Rogers, two shows that address the same question: 'What does it mean to be a good neighbor?'"

— Marah Gubar, Associate Professor of Literature

Hendershot: CNN and Sesame Street know that children may have heard this somehow and are really concerned. They obviously didn’t need to say that “the president suggested you should swallow bleach, but don't do it.” They didn’t go there, and that was absolutely appropriate. There were other moments where I was thinking, “wow, you have to really work hard to leave politics out in answering some of these questions about the pandemic.” Of course, they didn’t want to alarm children, but did you feel there were any moments where it would have been appropriate to include some kind of political angle in the conversation?

Gubar: Well, I noted that same moment when they did not mention the president, and I also thought that was fine. It was clear to the grown-ups who were watching what the reference point was.

Hendershot: And of course Sesame Street has always been aware that children and adults watch the show together. The CNN town halls tap into that history of parent-child co-watching to make the whole thing work. They built that into the show early on. Harry Belafonte’s and Pete Seeger’s guest appearances in the early 1970s did not have the same impact on a three-year-old that they would have had on her parents.

Gubar: Yes, the whole reason Sesame Street started using celebrities was to tempt grown-ups to watch with their kids. I guess I didn’t think, while I was watching the Covid-19 episodes, that they ought to have engaged in politics more, or notice them ostentatiously avoiding it — except for that one moment about not swallowing poison. Did you?

Hendershot: The other moment I thought was a little bit tricky was in the June 13 town hall when they had the Director of Health, from the Ohio Department of Health, and the question a child asked was, I see people outside all the time, but we’re not supposed to go outside. So how come they can go out and I can’t? And she responded in a very careful way, along the lines of: “Well, you have to remember that every family has different rules and that places have different rules. People obey the rules of their family or their place, and so what’s important is what you decide in your family.”

That was actually a moment to me of perhaps dropping the ball, given that what Sesame Street is so good at — as you pointed out earlier — and what CNN is tapping into with the whole concept of a town hall, is thinking about community. If the family next door decides that it’s okay not to wear masks when they leave the house, it’s not just a question of respecting the rules of the next door family. That family is perhaps not being compassionate about community, or acting empathically, an issue (empathy) that actually comes up explicitly in the town hall on racism.

I don’t have an easy answer for this. These days there are images on TV of people socializing, partying, etc. all the time, often in violation of CDC or statewide guidelines. Is there a way that this could be conveyed where you could say, well, you know people and places have different rules, but not everyone is following the rules? Without just being completely alarming to child viewers?

"What you’re pointing to is the difference between the network era and a post-network cable era and an era of social media, where everything is fragmented. The evening news offered a collective (if imperfect) shared sense of reality. There’s a nostalgia for the collectivity inherent in that, but then there’s the reality that it is not completely unattainable today, right? I think CNN has tapped into that in some ways with all their town halls."

— Heather Hendershot, Professor of Comparative Media Studies

Gubar: Yes, that was perhaps a dropped-ball moment in terms of actually spelling out what it means to say “we’re all in this together,” which they emphasize throughout the town halls. It didn’t bother me at the time because I interpreted that moment as meaning that someone in the staying-at-home family was immuno-compromised. So I thought it was just pointing to how some families do have different protocols than others.

Hendershot: It’s a difficult challenge for CNN. They’re trying to say “we’re all in this together” and promoting the idea of empathy and community without acknowledging that perhaps some people are not being empathic or, you know, embracing the idea of community. I’m not sure that that necessarily needed to be a consciousness-raising moment for children — I’m just wondering if it could have been done differently.

Gubar: Now that you mention it, it does seem like a lost opportunity because it would not have been that hard to have, for example, a conversation between two Muppets where one says, “Well, I’m not gonna wear a mask!” and then a discussion could have ensued. They could easily have done something like that, and it would have been in keeping with the spirit of the show, where characters work out disagreements and misunderstandings all the time.

Hendershot: There’s actually only limited interaction between the Muppets throughout the town halls, which struck me as a bit strange. In general, the Muppets are making guest appearances, and then we cut back to the adults, and the adults are often explaining things in a way that a three-to-five year old probably could not follow but that probably a ten-to-fifteen year old could. So that makes me wonder, who’s the audience for this really?

Gubar: Yes, exactly. The adults often said things like, “Oh, that kid’s so cute,” and I was thinking, “Really? Do we have to have adults gushing about how adorable the children are?” There was something about the tone that was a little strange if the audience was really young children.

Hendershot: Agreed. Also, I would have liked to have heard more from children. To be clear, I’m not suggesting that CNN got it wrong by not letting kids have a “rap session,” to use the language of the 1970s. In many ways they did a really good job. But it was kind of like a tennis match, with back-and-forth questions from kids answered by adults. That’s something that Mister Rogers would have done differently.

I think on the surface the CNN town halls look kind of perfect — they are really informative and helpful. But Mister Rogers would have looked at children (directly through the camera) and talked to them and then had some kids on and talked to them and asked them about feelings. He might ask, are you scared to wear a mask? Are you worried you can’t breathe in a mask? It would have been a very different approach, and in a way that would have perhaps taken the children more seriously. And along those lines, here’s where I'd like to hear a little about why you thought the Covid-19 town halls were stronger than the anti-racism town hall.

"The show started off strong with kids asking a really hard question: 'Why is there racism?' While I appreciate that it’s not as easy to talk about systemic things like how colonialism and capitalism have contributed to this problem, I think that kids could have benefitted from hearing adults try to answer this question in more complex ways."

— Marah Gubar, Associate Professor of Literature

Gubar: My main feeling about the racism town hall was that they kept making it a personal problem rather than acknowledging the systemic nature of racism, and this happened over and over and over again. I’m thinking for example of the moment when Van Jones says something like, “We hope people are going to have a change of heart,” as if the problem of racism is just a matter of changing individual hearts, not ending inhumane policies and practices that harm some groups more than others.

It also happened when the former police officer said, basically, well, there’s a couple of bad apples in the police force. And when Keisha Lance Bottoms, who I thought was wonderful in many ways, said that racism happens because “hurt people hurt people,” which again makes racism seem like a purely personal, psychological phenomenon. The show started off strong with kids asking a really hard question: “Why is there racism?” While I appreciate that it’s not as easy to talk about systemic things like how colonialism and capitalism have contributed to this problem, I think that kids could have benefitted from hearing adults try to answer this question in more complex ways.

Hendershot: So you would say that the “ABCs of Covid-19” town hall might not get into some political issues that it could have but that the sense of community is very strong, and that is in contrast to the individualizing impulse in the racism town hall?

Gubar: Exactly. They did not treat racism or policing as a neighborhood problem, by exploring how particular norms, laws, and policies have the power to affect the neighborhoods we inhabit and the kinds of interactions that we have — or don’t have — in them. Of course, it’s tricky to talk about these complicated structural issues, but the kids’ questions were so much bigger and stronger and more pressing than the way they were answered, as was the moving song that twelve-year-old Keedron Bryant sang about trying to live in a society that’s proven so deadly to other Black boys.

Hendershot: That’s a really good point, and I was thinking that the Covid questions are also difficult to answer in a way to satisfy a child. “Why can’t I hug my grandmother?” There’s a practical answer to that, but not an easy way to satisfy a child about the situation. But the racism questions were even harder and sometimes unanswerable, and there was a bit more evasion there and deflection by the adults.

"They did not treat racism or policing as a neighborhood problem, by exploring how particular norms, laws, and policies have the power to affect the neighborhoods we inhabit and the kinds of interactions that we have — or don’t have — in them. Of course, it’s tricky to talk about these complicated structural issues, but the kids’ questions were so much bigger and stronger and more pressing than the way they were answered."

— Marah Gubar, Associate Professor of Literature

Gubar: The moments I appreciated were the ones when adults didn’t offer an overly simple or evasive answer to a tough question, but instead admitted the limits of their own knowledge. For example, I thought it was terrific when they said, about Covid-19, “we don't know when it’s going to be over.” It’s great to hear grown-ups say, “that’s just something we can't be sure about.” Because with what’s happening in the U.S. right now, modeling epistemic humility has become, in itself, an implicit critique of the president’s discourse.

Hendershot: Yes. That’s something that we see in the town hall about racism too, where empathy becomes a key issue. I think that that is a guardedly political moment because we know that one of the refrains about the deficiencies of our president is that he seems incapable of empathy, and specifically around Black Lives Matter issues and around Covid-19 issues, right? So when CNN shows a whole segment praising the Muppet Abby Cadabby for her empathy for her friend Big Bird, who has experienced bullying because of his appearance, they are implicitly doing something political.

"Overall, it’s really interesting and impressive that CNN tried to do something that they considered sort of neutral, with these Covid town hall specials. CNN has a liberal orientation ...and their Covid coverage has political dimensions, but the Sesame Street town halls really attempt to be neutral and undertake a public service function....These COVID town halls are very “of the moment” but also feel evocative of a past sense of TV news’ public service mission."

— Heather Hendershot, Professor of Comparative Media Studies

I should add that it’s not like the issues these town halls address must be either emotional or political. Reading between the lines, we can see across all three of the CNN-Sesame Street town halls how issues can be political and emotional at the same time, and that an issue like empathy or the importance of community can be political without naming candidates or political parties.

Gubar: Right, absolutely. And I think that this is a broader trend in children’s culture as well, one that we see more clearly in the wake of the 2016 election. Of course, children’s movies and TV shows have often stressed the importance of kindness, compassion, and empathy. But I think creators of children’s culture have recently been trying to double down on this message because of the broader political and cultural situation we’re in right now.

Hendershot: Agreed. Overall, it’s really interesting and impressive that CNN tried to do something that they considered sort of neutral, with these Covid town hall specials. CNN has a liberal orientation and is often attacked by the president as “fake news,” and their Covid coverage has political dimensions for sure, but the Sesame Street town halls really attempt to be neutral and undertake a public service function. That was the remit of television news for decades during the network era, to be neutral, balanced, and objective. And that’s generally not what cable news is today, so CNN is doing something really special here in teaming up with Sesame Street for these programs. These COVID town halls are very “of the moment” but also feel evocative of a past sense of TV news’ public service mission.

Gubar: Definitely. And this reminds me of what we were saying at the beginning about Sesame Street being partly publicly funded and conceptualized for the public good. I was just reading about the loss of the nightly network news and how everybody used to watch, say, Walter Cronkite, at 6:00. Losing that is a kind of a destabilizing thing and contributes to people being atomized in their separate media bubbles. There’s nostalgia for when we had these publicly trusted figures doing the news.

Hendershot: What you’re really pointing to is the difference between the network era and a post-network cable era and an era of social media, where everything is fragmented. The evening news offered a collective (if imperfect) shared sense of reality. We don’t want to be too nostalgic about it, but there was at least a real attempt, in theory, to speak to everyone. There’s a nostalgia for the collectivity inherent in that, but then there’s the reality that it is not completely unattainable today right? I think that CNN has tapped into that in some ways with all their town halls, not just the ones for kids.

I’d add, too, that when Black Lives Matter demonstrations erupted in the days following George Floyd’s death, ABC, CBS, PBS, and NBC weren’t running that 24/7. They were including excerpts during their news programs. But with CNN you could go and just watch live coverage and feel others were watching too. There’s a potential feeling of collectivity in that, which is also inherent to the very notion of programs designated as “town halls.”

Gubar: Yes, and that’s the whole refrain of these CNN-Sesame Street collaborations. We’re all in this together.

Suggested links

Gubar's MIT webpage

MIT Comparative Media Studies