Indigeneity at MIT

A Conversation with David Shane Lowry, '03 ('07)

Distinguished Fellow in Native American Studies at MIT

David Shane Lowry, '03 ('07), Distinguished Fellow of Native American Studies at MIT

"Today, restoring the visibility of, and respect for, Native lives and identities is a profound form of healing — both for individuals and for entire communities."

David Shane Lowry '03 (‘07) is MIT’s Distinguished Fellow in Native American Studies, tasked with leading a conversation at MIT about the Institute and Native America. President Rafael Reif introduced Dr. Lowry in an August 2021 commentary titled "Facing a Difficult History."

"For some time," President Reif wrote, "we have been grappling with the legacy of MIT’s third president, Francis Amasa Walker, who led the Institute from 1881 until his death in 1897. A former US commissioner of Indian affairs, Walker played a major role in advancing the American reservation system, and in 1874 he published The Indian Question, a diatribe about Indigenous peoples.... The question we are working through now is what to do with these facts, as well as other aspects of the history of MIT and Native communities. Last year, MIT launched a class to examine the Institute’s connections to Native nations and tribal lands, the histories of Native communities in the region, and the history of MIT’s Indigenous students, faculty, and staff... This fall, we welcome Indigenous scholar David Lowry ’07, who will fill a newly created position."

A member of the Lumbee Tribe who trained as an anthropologist at MIT, Lowry focuses his research on how people and cultures heal. This fall and next spring, he is teaching the new MIT class, 21H.283/The Indigenous History of MIT, and engaging with people and groups across the Institute to further the work that President Reif describes above. MIT SHASS Communications recently spoke with Dr. Lowry about his perspectives and his endeavors at MIT.

____

Q: You are teaching the new class 21H.283/Indigenous History of MIT this year. What are your goals for this class, and what lessons do you hope students will carry with them into the future?

A: If you look into MIT’s past, you will see a complicated mosaic in which American Indian (Native American / Indigenous) people have been empowered to a certain degree, although this empowerment is shadowed by MIT's connections to damage to American Indian people and communities. So a primary goal of 21H.283/Indigenous History of MIT is to help students press into heavy, but important conversations to understand the Institute's relationship to Indigenous communities, including harms.

Related goals are to give Indigenous people permission to speak, to reinforce the value of their voices in the present, at MIT and beyond, and to set the stage for a reintroduction of Indigenous people in higher education. In using the word “reintroduction,” I am not suggesting that American Indians were members of higher education communities in the past. Rather, I am pointing to the fact that American Indians and our cultures have long been the subjects of academic study and scientific/medical experiments in centers of higher education. To “reintroduce” us into higher education is to move American Indians from being studied others to being respected voices in lecture halls.

A main lesson that I hope students will carry with them from the 21H.283 course is that it is OK to be part of a colonial* organization and also to challenge aspects of it that sustain historical injustices. At MIT, one such aspect is described by a simple, if difficult statement: MIT (like all of metro-Boston) is built on unceded Indigenous land, and benefits from policies and practices that have caused historic and ongoing damage to Indigenous peoples, nations, and ways of life.

___________________

*A note about the term “colonial": In my work, I use the term to reference institutions — schools, governments, churches, etc. — that have been established in places and situations that involve the erasure or significant diminishment of American Indian well-being and presence.

Aerial view of MIT, with Killian Court in the center

"One goal for this new MIT History course, 21H.283, is to give Indigenous people permission to speak, to reinforce the value of their voices in the present, at MIT and beyond."

Q. Do you use the terms American Indian, Native, Native American, and Indigenous People interchangeably? Are they all acceptable terms?

That's a good question. All of those terms are, in my view, legitimate terms used by the first peoples of the United States. I would also note that, to date, none of these terms are frequent in everyday conversation at MIT, and since one goal of my work is to help create an Institutional inclination to think of all the people represented by those identities, I like to bring all the terms into conversation. Another nuance about nomenclature is that while we Native people know who we are, we regularly spend time trying to decide which term will be the most helpful when we talk about ourselves to others.

I have preferred to use "American Indian" since 2014, when I was teaching medical students in Chicago, many of whom were first-generation Indian American. They knew nothing about American Indian people, including why we are described as "Indian." Class conversations during which an American Indian (me) explained to Indian American students that "Columbus confused my people for you," were moments of amazement and critical reflection on how European colonization continues to impact places where we create relationships of healing.

Q. As an anthropologist, you have studied human healing, particularly from the perspective of your own Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. What insights can you share from this research that might benefit people from other cultures and traditions?

A: In 2002, a group of anthropologists and other scholars came together, with support from the Fulbright Foundation’s New Century Scholars Program, and issued a famous report with the message, Identity Matters. We see this truth in various movements, from Black Lives Matter to the work of LBGTQ+ communities, and it is important to note that there is one group of people in America — Indigenous Americans, American Indians, Native Americans — whose identity has been nearly completely eclipsed.

Today, restoring the visibility of, and respect for, Native lives and identities is a profound form of healing — both for individuals and for entire communities.

To give one example of how erasure works in daily life: When I say in a conversation that "I am Lumbee” or “Indian,” I recognize that the person I am talking to may have a favorite Atlanta Braves or Kansas City Chiefs T-shirt or cap that portrays American Indians as a cartoon and a mascot. Such pop-culture emblems of Native Americans are a diminishment of our identity and humanity, a form of the casual disrespect that American Indian people experience regularly. One result is that, historically and into the present, American Indians have often adopted other peoples' identities: We became missionaries in European American churches. We became doctors and nurses studying in the medical schools of White and historically Black colleges.

In entering those other spaces and identities, American Indians are not simply being colonized, however. Instead, as I explore in a forthcoming book, American Indian people occupy dual realities that do not necessarily conflict. Our worlds and our ways of being have been muffled by layer upon layer of settler occupation over the last 500+ years. At the same time, we are also creative explorers — so we find ways to benefit, selectively, from colonial realities (even ones built on our unceded lands) for the sake of our communities' survival, well-being, and legacy. Such dual identity is a condition for all colonized peoples, who must frequently adapt their public images and voices to the cultural standards and worldviews of cultures that are not their own, in order to gain work, and social and professional credibility.

That phenomenon is one reason it is so valuable for forward-thinking institutions like MIT to provide new avenues — roles, opportunities, support — for American Indians to be heard, including in protest. Empowering more voices from Indigenous communities at MIT will bring new knowledge, ways of thinking and being, and forms of creativity to the Institute. It will also bring ideas for actions* to help modify, improve, or even dismantle certain colonial realities to which MIT has been connected.

___________________

*One positive example of such action is the University of Hawai'i's recent project for stewardship of Maunakea, a mountain that is both a sacred, cultural heritage site for Indigenous Hawaiians, and one of the finest locations for astronomy on the planet. The developing plan, which honors both Native Hawaiian sovereignty and the scientific quest, will remove five of the 19 telescopes currently installed on the summit of Maunakea, restore the former sites as fully as possible to their original condition, and, going forward, sustain a balance of the cultural, scientific, and heritage activities on the mountain.

An MIT Press Reading List for Native American Heritage Month

Native American Heritage Month takes place in November, "paying tribute to the ancestry and traditions of America’s Indigenous peoples. This year we commemorate the month with a selection of works that examine issues of importance to Native Americans nationwide, while also acknowledging the complicated history of both the Institute and the Press with respect to native peoples and lands." — via the MIT Press

Q: While some might see the colonization of America as an historic problem, your work underscores the ways in which Native Americans continue to be marginalized. Can you share some examples of this phenomenon, as well as some ways in which this marginalization might be redressed?

A: Recently, MIT issued a video on the work of the MIT Values Statement Committee in which faculty and community members spelled out the values of MIT. I was not surprised that no member of the committee was American Indian, but reading the statement, it hit home for me that non-Indigenous peoples truly do not feel the discordance in the act of articulating a values statement — in the absence of American Indian minds — while occupying unceded American Indian land.

In particular, I was struck by one committee member’s statement that we must “learn from the past” — an important point that I respect deeply. The question that arises for me is how is it possible to learn from the past in institutions that do little to incorporate the perspectives, narratives, and values of the Indigenous people who have been an indelible part of that past, and are still here today. I find it perplexing that Americans believe they can have good moral standing while living in a society that has accepted and profited from genocide of American Indians. It's also concerning that so many feel that it is OK to make consequential decisions that affect American Indians with no input from American Indians.

My research suggests that a colonial moral framework informs many academic disciplines; one consequence is that students can complete their years at a university and go forth into professional careers where they are compensated for work that continues to damage Native American communities. Even today, as some American Indians are standing up to protect their lands from gas pipeline companies across the United States and Canada, they may stand toe-to-toe with MIT-trained engineers who work for those companies. That our own alumni are often unaware of such damage is likely related to the fact that none of their MIT professors have been Indigenous Americans.

Can such conditions change? Can the Institute contribute to remedying this limitation in the culture and the academy? These are among the questions I want to explore at MIT, drawing on this community's extraordinary collective intelligence and dedication to making a better world.

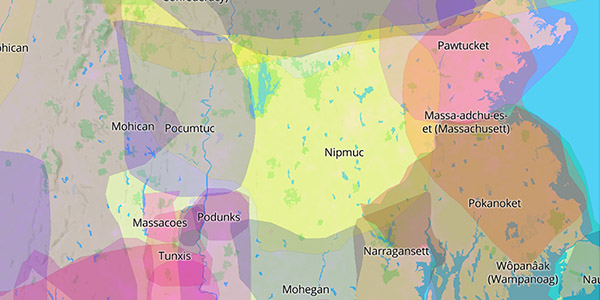

Detail of an interactive Indigenous territories map by Native Land Digital

"The traditional territory of the Massachusett people consisted of the narrow coastal plains along Massachusetts Bay in what is now eastern Massachusetts." Along the coastline their lands ran between present day Salem and Brockton, and "from the coastline, the Massachusett territory extended roughly twenty miles inward."

— Entry on "Massachusett," in Wikipedia

Q: President L. Rafael Reif and many MIT faculty have committed to addressing the Institute’s difficult history related to Native Americans, work that is now accelerating with your appointment and the conversations you are leading at the Institute. What is your vision for how MIT might better support Native American students, alumni, and communities going forward?

A: I am greatly encouraged that MIT leadership and the community are considering MIT's mission statement in relationship to Native America, becoming engaged with the historic and contemporary issues of our peoples and nations, and supporting American Indian presence in the Institute’s life and education. These efforts express the ongoing reflection, commitment to facts, and capacity for problem-solving that characterize MIT and may guide the Institute toward a leadership role in addressing persistent injustices for Native America.

In October, on Indigenous People's Day, I hosted a conversation with MIT’s Native American students (including members of MIT NASA) to explore how MIT can act on its debt to Indigenous cultures and help remedy damages. Here follow some ideas that emerged in that conversation. To bring American Indian presence, knowledge, and perspectives more fully into the MIT community, the Institute could:

- Forgive tuition and college loans for American Indian students;

- Include representatives of American Indian communities on the Corporation;

- Hire American Indian scholars, including in tenure-line faculty positions;

- Support the ingenuity and entrepreneurship of Native American students;

- Hire staff and administrators from American Indian communities;

- Support the American Indian community as a distinct entity within MIT, for example with a Center for Indigenous Futures located in the Walker Memorial building.

These are a few ideas that I look forward to exploring with the Institute community. During that same Indigenous People’s Day gathering with Native students — as we brainstormed ways to bring more Indigenous presence to MIT — one student observed, astutely, that the MIT name itself is already very Indigenous!

Massachusett, of course, is the name of the American Indian tribe on whose unceded land all of metro-Boston and Cambridge now exists: "The traditional territory of the Massachusett people consisted of the narrow coastal plains along Massachusetts Bay in what is now eastern Massachusetts. From the coastline, the Massachusett territory extended roughly twenty miles inward." I hope and trust that over the coming years, the Institute, where I first gained the knowledge and skills to think about matters of race, equity, and colonization, will find innovative, meaningful new ways to honor the “Massachusetts” dimension of its name — and all that it means.

Suggested links

MIT Webpage: David Shane Lowry

Commentary by MIT President Rafael Reif: Facing a Difficult History

Course: 21H.283 / The Indigenous History of MIT

Students work with MIT faculty, staff, and alumni, as well as faculty and researchers at other universities and centers, to focus on how Indigenous people and communities have influenced the rise and development of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Students build a research portfolio that will include an original research essay, archival and bibliographic records, maps and images, and other relevant documentary and supporting materials.

MIT Native America Student Association (MIT NASA)

MIT NASA seeks to provide social, political, cultural, and academic support for MIT undergraduate and graduate students of Native American descent and Native student allies.

American Indian Science & Engineering Society (AISES)

Readings

An Obituary for Alfred Kroeber, or Can American Indians Speak? by David Shane Lowry

MIT Press Reading List for Native American Heritage Month, November 2021

Oxford Bibliography on "Indigeneity"

Identity Matters: Ethnic and Sectarian Conflict

Peacock, Thornton, Inman; New York: Berghahn Books, 2007

Additional Resources

Native Land Digital: Interactive Indigenous Territories Map

pre-colonial territories of the Native American peoples

Website: Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina

Boston Globe: MIT grapples with early leaders stance on Native Americans

Facing History: Indigenous Rights and the Maunakea Telescopes

NBC Video: Why Native Hawaiians want to protect Mauna Kea from more giant building projects

Manuakea Stewardship Plans | University of Hawaii

Published 15 November 2021

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Office of the Dean

MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences