World premiere of Charles Shadle's Symphony No.4

Composer's Commentary + Webcast

Webcast: Performance of Symphony No.4

Professor Shadle's fourth symphony starts at 59:00 on the webcast.

Charles Shadle | Related: Choctaw Animals

Program Notes for Symphony No.4

1. Sereno-Allegretto energetico

“As Adam early in the morning...”

2. Scherzo-Trio-Scherzo (Reprise)

“Day full blown and splendid—day of the immense sun, action, ambition, laughter…

3. Night on the Prairies

(Text adapted from the poem by Walt Whitman)

Night—The supper is over, the fire on the ground burns low,

The wearied emigrants sleep, wrapt in their blankets;

I walk by myself—I stand and look at the stars, which I think now

I never realized before.

Now I absorb immortality and peace,

I admire death and test propositions.

How plenteous! How spiritual! how resumé!

The same old man and soul—the same old aspirations, and the

same content.

I was thinking the day most splendid till I saw what the not-day

exhibited, I was thinking this globe enough till there sprang out so noiseless

around me myriads of other globes.

O I see now that life cannot exhibit all to me, as the day cannot,

I see that I am to wait for what will be exhibited by death.

Composer's Commentary

I marked the passing of my mother in my Third Symphony, and this one celebrates and commemorates my father. They form a pair, and even share some musical ideas, but each is complete, in and of itself; musical monuments for two compatible but very different people.

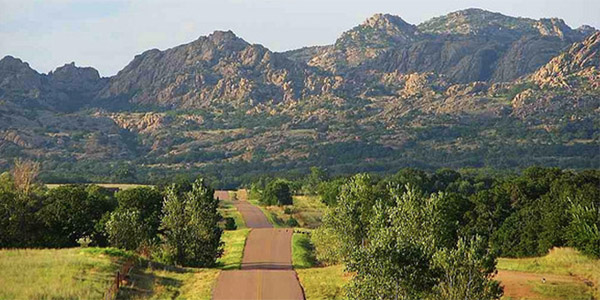

My Symphony No.4 is a cyclic work. Musical ideas, as in the French Symphonists or Mahler, recur in each movement, but this symphony also engages with other ideas that are “cyclical.” The trajectory of our lives is suggested in the movements — Youth, Maturity, and Old Age, and the times of the day, and even the progression of the seasons are present. Despite the occasional stylized bird call, or hymn-tune fragment, the work is not essentially programmatic. It doesn’t tell a specific story, though many extramusical elements shaped and suggested the music. Mood and evocation are more important than illustration, though I do understand it as an “outdoors” piece, and much engaged with the idea of the American landscape. I have selected quotations from Walt Whitman to indicate some of the affective content, and of course, the final movement sets most of that poet’s "Night on the Prairies."

The first movement, Sereno-Allegretto energetico begins with a solemn and rather monumental Introduction. This Introduction serves as a sort of musical storehouse for ideas, some of which can be simply cast aside, while others become extremely important throughout the entire Symphony. The following exposition features a quick theme with an exuberant lilt, and a slower second theme that is naïve, even a little callow in character. There is no real development, just a short transition to a recapitulation. Here the first theme is abbreviated, but the second theme grows and develops, gaining in gravity, and expands into a lengthy coda, much influenced by the opening introduction. The movement ends with first theme asserting a sense of optimistic energy and exuberance.

The middle movement opens with a Scherzo, driven, militaristic, and insistent in the presentation of an obsessive rhythmic motive. Unlike the first movement, it is in full Sonata form, with an extensive development section. I composed it after a visit to Jacksboro, Texas (site of my Father’s grandparents’ ranch) on a hot, summer afternoon, and I hope that some of the intense heat reflecting off the white limestone facades of the courthouse square, has made it into the music. The central Trio is a cowboy song for paired clarinets, that seem to droop, like living things, under the Noonday sun. The Scherzo is reprised, though abbreviated to just the recapitulation, and with an inexorable, hammering coda.

In the final movement, Night on the Prairie, the orchestra evokes the vast, rolling Plains at dusk, setting the scene — “I walk by myself — I stand and look at the stars” — for the entrance of the baritone soloist. Whitman’s poem is very much of the of the 19th century, an era of unquestioning expansion and colonization, but centers on the perception that we must understand ourselves in terms of an expansive embrace of the infinite, of that which is outside of our selves. Just as the singer seeks to “test propositions” and “absorb immortality” the music of this movement continually refers to earlier moments in the symphony, but rather than ending in that terrestrial landscape, it reaches toward the star-studded vault of the firmament. — Charles Shadle, May 2022

Comment before the Performance

When I first started imagining my Symphony No.4, in the time before the plague, I kept returning to Walt Whitman’s poem, "Night on the Prairies." I found it magically and musically evocative, but one word, kept standing out to me. That word is “emigrants.” Whitman obviously writes about white settlers advancing across the emptiness of the great American dessert — but we know now that it was never empty, never “free for the taking.” But this word, “emigrants” shouldn’t divide us — and though it may be a truism, we are all in some sense emigrants here.

Perhaps your ancestors arrived on the Mayflower, or perhaps they walked here from Asia. Perhaps your people came here, unwilling and enslaved, or fleeing persecution and intolerance. But we are all here now — and we have come to understand that from individuals we become a community, and as orchestral musicians know, community makes us strong.

My own Choctaw people know a thing or two about journeys. You may have learned about our Trail of Tears — the forced removal of American Indian people to Oklahoma in the 19th century. But we also tell an older story of a long journey from far in the west to our historic Mississippi homeland. It was a long trip, and we could take only a few things we needed, like the bones of our ancestors, and we knew that many of us would not see journey’s end. We understood that the important thing was the act of moving forward into hope.

And this brings me back to Whitman’s poem, where the poet realizes that the “globe is not enough" — that there are other worlds and ways of being, revealed in the immensity of the nighttime skies.

And here is the cautionary note that we take from our emigrant ancestors. We have moved across the Earth with less concern for each other than we should have had. If, as seems likely, we are to emigrate into the expanses of the cosmos, might we not require ourselves to be more aware, more cognizant of the ambiguities and complexities of the enterprise? Certainly, we will want to carry the valuable bones of the past with us, but we will want to be careful to respect the “myriads of other globes” that we will encounter.

Sggested links

Webcast: Performance of Symphony No.4

Professor Shadle's fourth symphony starts at 59:00 on the webcast.

Charles Shadle