In Memoriam | Leo Marx: 1919-2022

Internationally respected and beloved, Marx created a new lens for American history studies — and was a leader in bringing the humanities into a central academic role at MIT.

Leo Marx, 1955; photo via the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation

"For over four decades, Leo Marx's work focused on the relationship between technology and culture in 19th- and 20th-century America. His research helped define the area of American Studies which understands scientific and technological activities in the context of broader American society and culture."

— Rosalind Williams, Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Science and Technology, Emerita

Leo Marx, internationally famed scholar of American history and founding member of MIT’s Program in Science, Technology, and Society (STS) died on March 8, 2022, at his home in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston. He was 102. Respected and beloved as scholar, teacher, colleague, and friend, he provided decisive leadership in giving the humanities a central academic role at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

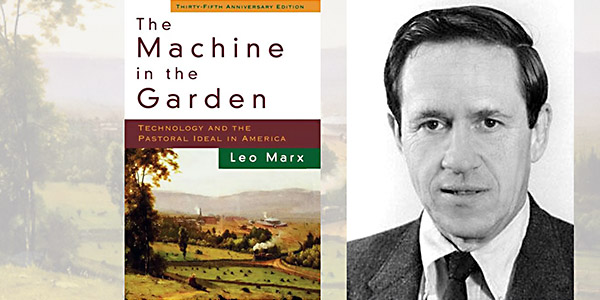

Marx, the William R, Kenan Jr. Professor of American Cultural History, emeritus, is best known as the author of The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (Oxford University Press, 1964). Based on his Harvard doctoral dissertation, the book identifies a fundamental contradiction in American literature and life. The wide open American landscape seems to incarnate the imagined “middle landscape” of the ancient Greek and Roman pastoral poets, where human beings live in harmony with the rest of nature. At the same time, the rich and expansive New World encourages ambitions for the mastery of nature. In America, pastoral dreams of harmony coexist with machine dreams of control.

A new lens for American history

The book title has become a familiar phrase, but it is the subtitle that best reflects the book’s complex theme. The “pastoral ideal,” which dates to antiquity, refers to a mode of literature that idealizes country life. The idea of “technology” dates back at most a couple centuries and has become identified with practical, money- and power-making enterprises such as employment, engineering, management, warfare, and production. How could these two words and ideas belong in the same title? What do they have to do with each other and with American history?

Marx was among the first in the U.S. academic world to practice deeply interdisciplinary scholarship. He highlighted the role of literary analysis in understanding technological history, because, as he wrote in a syllabus for one of his graduate classes, imaginative writers “rarely take technology and its relations with the rest of society and culture as their primary or explicit subject. Indeed, it is precisely the kind of indirect or tacit significance attributed to the role of technologies in literary works that makes studying them particularly valuable.”

This was a new approach in mid-20th century historical studies, and it provided a sharp new lens for viewing both American history and industrial history. Marx used this lens to study images and episodes that are dramatic and revealing: the whistle of a steam train shattering the quiet woods of Thoreau's Walden, or a steamboat crashing into a raft on which an enslaved Black man and a white boy float down the Mississippi in Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

The Lackawanna Valley, a painting by George Inness, c. 1855, appeared on the cover of "The Machine in the Garden."

"Through additional essays and articles, Marx ultimately built up an intellectual history of the concepts of nature, environment, technology, and progress, as these terms continued to co-evolve. Even today, the seeds of his ideas sprout up in countless reviews, conversations, and classroom discussions."

The making of a classic

Getting from the basic insight — the power of imaginative literature in understanding technological change — to a published book took Marx a long time. As an undergraduate at Harvard College in the late 1930s, concentrating in History and Literature, he was already intrigued by ways that imaginative writers in America engaged with the emerging power of industry. When he graduated in 1941, however, the world was at war. He joined the U.S. Navy and spent most of the next four years serving on and eventually becoming captain of a subchaser.

After the war’s end in 1945, Marx returned to Harvard University as a doctoral candidate in a program titled History of American Civilization. He happened to read a book review claiming that an American writer of the 1890s was among the first to respond to industrialization. This assertion struck him as obviously wrong, because he could immediately think of writers (among them Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and even Thomas Jefferson) who had responded to industrialization much earlier.

So, in his doctoral dissertation, Marx provided a fuller and more accurate account of early responses to industrialization in America. He received his PhD in 1950 and went to work in the English Department at the University of Minnesota. With his wife, Jane Pike Marx, whom he had married during the war, Marx moved to Saint Paul. He began to hone his teaching skills at Minnesota's large and well-regarded public university, while also serving as a visiting professor at other institutions, including the University of Nottingham in England and Amherst College in Massachusetts.

In 1958, Marx accepted an offer to join the Amherst faculty as professor of English and American Studies. Then almost 40 years old, and still revising his dissertation, Marx asked one new colleague for what he hoped would be a final review. Benjamin DeMott’s feedback was: “This is a good book about other books. If you make it into a book about America, you will have a great book.”

Marx responded with a thorough revision, and The Machine in the Garden was finally published six years later. “From day one, The Machine in the Garden was considered a history of technology classic,” says MIT's Merritt Roe Smith, the Leverett and William Cutten Professor of the History of Technology. It was also, he adds, a “pioneering work that helped, more than any other book, to define the field of American studies during the 1960s.” While almost 60 years have now passed since the book's appearance, its scholarly quality, originality, and significance continue to stand the test of time.

Leo Marx, c. 1960s; 25th anniversary edition cover of The Machine in the Garden"

"At this point in American history it’s unimaginable to talk about anything of substance without talking about technology, the environment, and the American dream. This book was out in front. It’s about environment and technology before those two words became defining words of the history of science and technology."

— Rosalind Williams, Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Science and Technology, Emerita

Origin story

Marx stayed at Amherst for 18 years, earning a reputation as a legendary teacher. In 1975 he accepted an invitation from MIT President Jerome Wiesner, Provost Walter Rosenblith, and historian of technology Elting Morison, to come to MIT to help develop a program in technology studies. More than another academic department, Wiesner, Rosenblith, and Morison intended to create a College of Science, Technology, and Society, connecting all of MIT’s existing schools in a mission that would include an undergraduate program, research center, and fellowships.

Marx joined the MIT faculty as the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of American Cultural History, but the ambitious plans for a new College gradually ran into fiscal limitations, staffing disputes, and insufficient undergraduate student interest. Although Marx and his colleagues prepared an innovative “window course” featuring interdisciplinary readings and lectures, undergraduates at the time were not yet deeply engaged with the issues of technology and science in society. The experiment lasted five years, and planted many seeds for the future, before being cancelled in 1982.

Wiesner and Rosenblith had retired from MIT leadership in 1980, and aspirations for creating a College subsided with their departure. What was left was a very fine Program in Science, Technology, and Society (STS) in the School of Humanities and Social Science, the forerunner of today’s School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. The existence of STS remained threatened, however, as the MIT leadership of that time was not yet persuaded that the pastoral ideal, nature, and technology had much to do with each other.

To attain stability, STS faculty worked to launch a graduate program, and in 1987 got provisional approval for what is now known as MIT's Doctoral Program in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology, and Society (HASTS). The great success of the HASTS program proved pivotal in launching STS into its current status as a leading STS program, highly regarded within and beyond MIT.

Throughout this period, Marx was “the intellectual heart and soul of the STS program — in large part because he believed in it so much,” says Sherry Turkle, the Abby Rockefeller Mauze Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology. When STS became stabilized in 1990, Marx had been at MIT for 14 years and was one of the last MIT faculty subject to mandatory retirement. However, retirement seemed only to reinvigorate him: as Kenan Professor Emeritus and Senior Lecturer, Marx continued to publish and to teach almost every semester through 2010.

Leo Marx with students at a gathering to honor his last formal graduate seminar, 2010. Photo: Margo Collett

"Marx leaves a rich legacy as a teacher — influencing not only students but colleagues. 'Everyone in the program wanted to teach with Leo, and in turn, every one of us, I think, did because it was a profound mentorship in how to make a classroom work,' Turkle says, adding how impressed she was by 'Leo’s ability to turn a seminar into a humming collaborative experience.'"

The meanings of nature, environment, technology, progress

By the 1990s, Marx’s scholarship had been moving towards interdisciplinary environmental studies — where nature and technology converge — and by the later 1990s, interdisciplinary environmental studies had become a major area of research in historical and cultural studies. Along with Jill Ker Conway and Kenneth Keniston, Marx organized a multi-year lecture and discussion series that eventually led to a book intended for a general audience: Earth, Air, Fire, Water: Humanistic Studies of the Environment (University of Massachusetts Press, 2000).

At the same time, technology was increasingly being identified exclusively with digital devices and systems. For many decades Marx had been exploring the meaning and evolution of technology in a string of publications including articles about Heidegger’s concept of technology, about technological pessimism, and about the concept of progress. All these studies converged in an article titled “Technology: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept,” first published in 1997, and then again in the journal Technology and Culture in 2010.

To challenge the key concept in the history of technology as “hazardous” is both provocative and persuasive: Marx’s article has become among the most-cited in the long history of Technology and Culture. Through additional essays and articles, Marx ultimately built up an intellectual history of the concepts of nature, environment, technology, and progress, as these terms continue to co-evolve. Even today, the seeds of his ideas sprout up in countless reviews, conversations, and classroom discussions.

Humming classrooms

Marx also leaves a rich legacy as a teacher — influencing not only students but colleagues. “Everyone in the program wanted to teach with Leo, and in turn, every one of us, I think, did because it was a profound mentorship in how to make a classroom work,” Turkle says, adding how impressed she was by “Leo’s ability to turn a seminar into a humming collaborative experience.”

David Mindell, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics as well as the Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing, is both an STS colleague and one of Marx’s former STS graduate students. He says Marx’s standards for good writing were clear and high. “One could not ask for a kinder, gentler person to slice a young scholar’s early writings to the bone,” he says, noting that Marx once gave him 11 pages of handwritten comments on one of his drafts. “He made me a better writer, a better thinker, and a better historian, and left similar marks on many others.”

Beyond MIT, Marx turned the world into his classroom. He did an enormous amount of public speaking, mentoring, editing, advising, and debating in all sorts of settings, all around the globe. Although he was an “Americanist,” whose sources were American history and literature, Marx had an international following, especially in Europe. David Nye, a former Amherst College student of Marx's who has spent most of his professorial career in Denmark, reflects “I doubt there is a single nation in Europe that he did not visit to attend a conference or give a lecture.”

Wherever he went, Marx was also treasured for his ability to listen closely. “Leo’s quality of mind was exhibited time and again in public settings," Smith recalls. "He had the extraordinary ability to ask very perceptive, penetrating questions." Nye adds, “Leo was a fantastic listener and gave incisive advice.”

An ongoing legacy

Today, Marx’s insights live on. A few weeks before his death, Marx’s daughter was contacted by Klaudio Štefančić, curator of the National Museum of Modern Art in Zagreb, Croatia, who was seeking permission to use the title “The Machine in the Garden” for a forthcoming art exhibition on “Pursuing the Representation of Machine Technology in Croatian Art.” Marx admired the catalog and poster for the exhibit and was pleased to see his inspiration at work in an unexpected quarter.

For his part, the curator says Marx's book inspired him “to search for broad meaning in art and to work in an interdisciplinary way.“ In his catalog essay, Štefančić provides a substantial summary of The Machine in the Garden, which has not yet been translated into Croatian. Then, through a close reading of key paintings in the exhibit, he shows how the tension between the pastoral ideal and social change might be found in Croatian visual arts beginning in the early 20th century. Štefančić extends Marx's insights to another time, place, and art, showing how they continue to provide a framework for understanding the modern world. The essay concludes: “We will not be able to imagine future society without the symbols of the garden and the machine.“

— MIT professors Rosalind Williams (emerita), David Mindell, Merritt Roe Smith, and Sherry Turkle; professor emeritus David Nye of the University of Southern Denmark; and family member Lucy Todd Marx, contributed to shaping this remembrance.

Suggested Links

Leo Marx

Wikiepedia entry

MIT Program in Science, Technology, and Society

Website

Books by Leo Marx

The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (OUP, 1964)

The Pilot and the Passenger: Essays on Literature, Technology, and Culture in America (OUP, 1988)

Editor (with Merritt Roe Smith), Does Technology Drive History?: The Dilemma of Technological Determinism (MIT Press, 1994)

Editor (with Bruce Mazlish), Progress: Fact or Illusion? (University of Michigan Press, 1996)

Articles

The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept

Technology and Culture, Volume 51, Number 3, July 2010, pp. 561-577, Johns Hopkins Press

The Idea of Nature in America

Daedalus, Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Spring 2008

Archive Stories

3 Questions with Rosalind Williams

on The Machine in the Garden, by Leo Marx

MIT symposium honors 50th anniversary of "The Machine in the Garden"

About

The pastoral genre in literature

Leo Marx with (L to R) his daughter Lucy, wife Jane, and daughter-in-law Katherine,

at the family's Maine cottage, 1970s

MIT professors Rosalind Williams (emerita), David Mindell, Merritt Roe Smith, and Sherry Turkle; professor emeritus David Nye of the University of Southern Denmark, and family member Lucy Todd Marx contributed to writing and shaping this remembrance.

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Contributing Editor: Kathryn O'Neill

Editorial and Design Director: Emily Hiestand

Published 8 April 2022