ELECTION INSIGHTS 2022

Research-based perspectives from MIT

Broken jobs, broken media, and working-class voters

Christine Walley

Professor of Anthropology

Perspectives for the 2022 Midterm Election

Main Page

Christine Walley is Professor of Anthropology at MIT. She received a PhD in anthropology from New York University in 1999. Her first ethnography Rough Waters: Nature and Development in an East African Marine Park (Princeton University Press, 2004) explored environmental conflict in rural Tanzania. The Exit Zero Project used family stories from the former steel mill region of Southeast Chicago to examine the long-term impact of deindustrialization in the United States. It includes an award-winning book with University of Chicago Press (2013), as well as a documentary film made with director Chris Boebel (2017). Chris Walley and Chris Boebel have also collaborated with the Southeast Chicago Historical Museum and web designer and artist Jeff Soyk to create an interactive archive and storytelling website sechicagohistory.org. The website uses objects that Southeast Chicago residents saved and the stories they told about them to explore the transformation of what it means to be “working class” in the United States. Walley is also working on a book based on this material tentatively titled, Notes from a ‘Paraindustrial’ Age.

Every day, my grandfather, a U.S. steelworker with a sixth-grade education, religiously read the newspapers in his high-backed chair by the window. My family lived one block away. Our neighborhoods in Southeast Chicago, along with Northwest Indiana, formed the Calumet region defined by the river at its center. Once one of the largest industrial corridors in the world, it surpassed Pittsburgh in the 1950s as the world’s leading steel-making district.

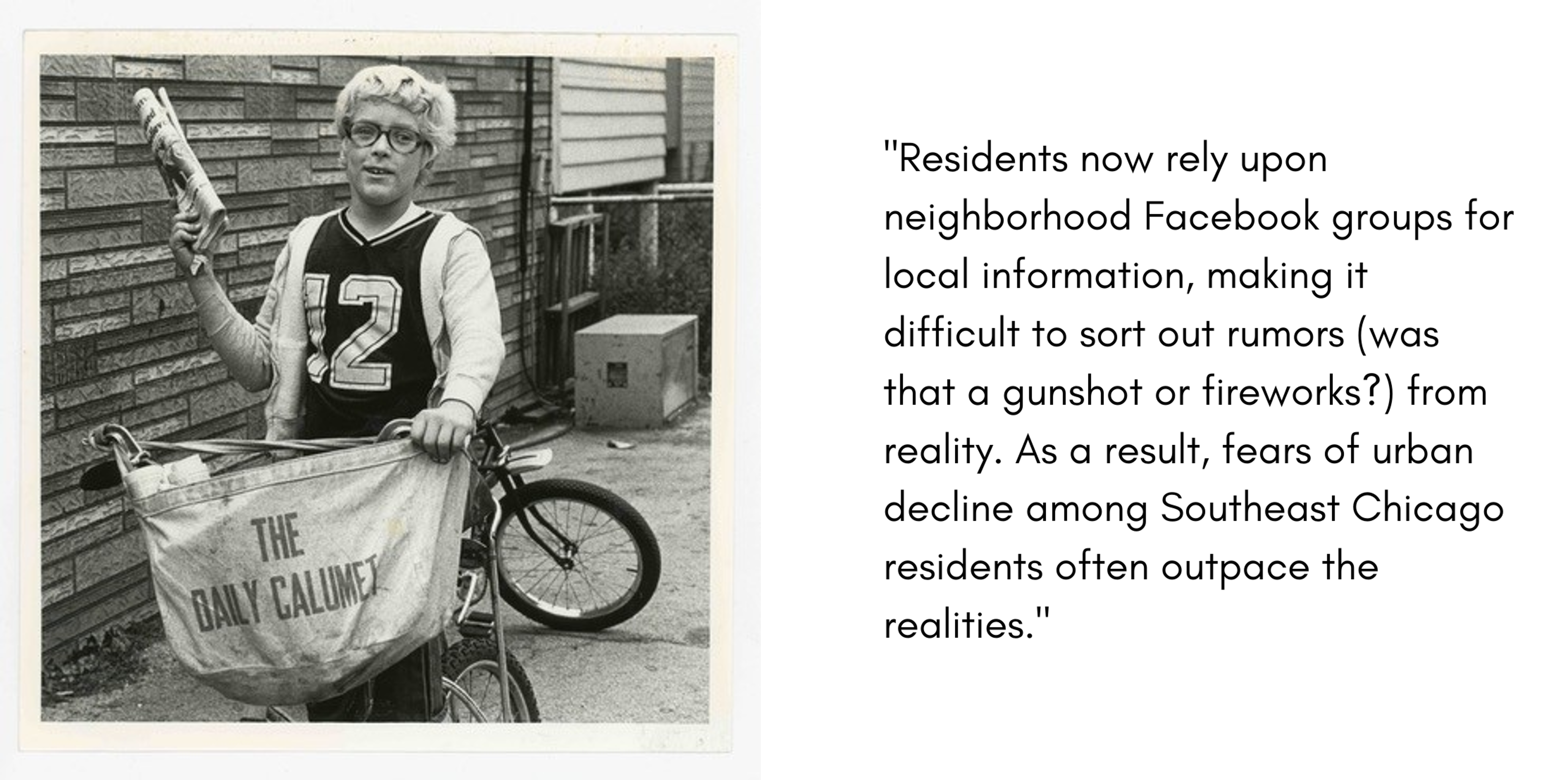

My father, also a steelworker, would stop at the neighborhood newsstand each day to pick up the Chicago papers, including The Daily Calumet, which claims to be the longest-running daily community paper in the United States. He also brought home union newsletters that provided economic analyses highlighting workers’ interests for the approximately 120,000 steelworkers and their families residing in the Calumet region, offering a counterweight to industry-sponsored publications and business press accounts.1

In short, for those I knew growing up, accessing a range of news sources, politically positioned in different ways but largely accurate, was as much a daily ritual as debating the news itself.

Economic inequality has exploded in the United States since the 1980s and 1990s, the period when the steel mills of Southeast Chicago disappeared. As in much of the country, the results of this inequality are starkly apparent in Chicago, with its beautiful gentrified lakefront city center and its largely decimated former industrial neighborhoods on the South and West Sides. The story of industrial decline and its presumed influence on shifting voting patterns in the United States became a commonplace (if not always accurate) narrative after the 2016 presidential election.2

More recently, it has been the explosion of misinformation and disinformation and its disruptive effects on elections that has generated broader concern. The two are related, but the linkages require closer analysis than commonly given: what has the disappearance of local newsstands meant for places like Southeast Chicago that are still experiencing what Sherry Lee Linkon describes as the “long half-life” of deindustrialization3?

I argue that the broken jobs and broken media environments stem from similar sources, creating a vicious cycle that encourages mis/disinformation, obscuring issues most relevant to working-class voters, and leading to political outcomes potentially contrary to what some imagine they are voting for. Connecting the dots is critical, not only for the 2022 midterm elections, but for the future viability of U.S. democracy.

Media transformation in the aftermath of industrial job loss

Southeast Chicago, the ongoing site of my research, is now a largely Latinx neighborhood with pockets of both white and black residents. Its media landscape has been vastly transformed since my childhood. The Daily Calumet is long gone, along with most other local newspapers in the United States.4

Residents now rely upon neighborhood Facebook groups for local information, making it difficult to sort out rumors (was that a gunshot or fireworks?) from reality. As a result, fears of urban decline among Southeast Chicago residents often outpace the realities. (For some, such views are buttressed by right wing media that implicitly or explicitly links urban violence in Chicago to racial demographics rather than the loss of industrial work that caused economic decimation for Latinx, white, and black residents alike).

Facebook is also the pervasive medium of communication for the local alderwoman, or city council representative, as well as churches and other community organizations. While these online connections are often vibrant forms of community-making in their own right, the heavy reliance on social media means that mis/disinformation actively seeks out Southeast Chicago residents.

The speed and power of false news

Since 2016, we have learned a great deal about the circulation of online mis/disinformation and the factors that contribute to it. We know, for example, that inaccurate news travels six times faster on Twitter and that some misinformation is the inadvertent byproduct of ordinary people sharing emotionally charged and unexpected news items often without reading beyond the headlines.5

We also know about the economic incentives built into algorithms that serve up content designed to entice people to click regardless of accuracy, as well as active disinformation campaigns by malevolent actors, including state-based ones. While we all live in a contemporary context that requires navigating minefields of potentially inaccurate information, what particular challenges do such realities pose for regions like Southeast Chicago?

Creating a media vacuum in working-class communities

Online mis/disinformation is a critical issue for working-class audiences. As trusted news sources retreat behind paywalls, less-trusted and freely available sources often target working-class populations.

Such dynamics, however, are not limited to online media nor are they all recent in origin. Scholar Christopher Martin, for example, documents how city newspapers in the United States in the mid-twentieth century assumed their readerships would cross class boundaries and regularly directed content towards working-class constituents and their interests. He argues that a crucial transformation occurred when conglomerates began buying up news organizations in the 1980s, insisting on an enhanced bottom line that sought to increase profitability by seeking out additional advertising revenues through an appeal to upscale consumers. The result was the abandonment of working-class readerships.6

This business strategy generated a media vacuum for working-class audiences that later presented opportunities for others to engage in news distortion or outright deception. Right-wing media in particular began targeting working-class and lower middle-class whites, often pitting them against working-class populations of color, echoing the ways white steel mill managers of old pitted working-class groups in Southeast Chicago against each other by deliberately using incoming ethnic and racial groups as strikebreakers to counter worker unity and unionization.

Corporate restructuring, media transformations…

The media transformations caused by the conglomerate takeovers that Martin identifies have their roots in the corporate restructuring of the 1980s that also led to the collapse of Southeast Chicago’s steel mills. While many assume that the U.S. steel industry went into decline solely because of global competition, such narratives neglect the crucial role that corporate restructuring played in encouraging systematic disinvestment in U.S. industry as well as in creating what David Weil calls the “fissured workplace” with its systematic shedding of jobs and proliferation of contract and temp work.7

Although some today might counter that jobs in 2022 are now plentiful and workers scarce, the current resurgence of union activity is an indicator of the low pay, stingy benefits, and difficult working conditions a range of industries offer employees.

The results of transformed media ecologies are impossible to escape. The rise of cable news in the 1980s and '90s, the demise of the Fairness Doctrine, and the regulatory failure to oppose media consolidation have created spaces for right-wing media companies like Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation and Sinclair Broadcasting to buy up local newspapers and broadcasters across the country (although Chicago’s markets have fared better than many others).8

At the same time, conservative billionaires have sponsored media campaigns attacking government policies they dislike as well as the unions that once made steel mill jobs “good” ones.9 Given the disproportionately heavy reliance of working-class populations of all races on local news sources, such factors are highly destabilizing (despite the fact that working-class blacks unsurprisingly avoid the racist dog whistles of Fox News and segments of the Latinx population rely heavily on Spanish-language television).10 In addition, working-class residents of all racial groups in Southeast Chicago suffer from the loss of union-sponsored news that once provided a counterpoint to business press narratives dominated by the viewpoints of the wealthy.

…and undermining democracy

Stemming the effects of mis/disinformation on our elections entails far more than media literacy training; it means identifying the structural factors and vested interests that got us here. It also means recognizing how the destabilization of both jobs and media are products of corporate restructuring and the dominance of free market and anti-regulatory values,11 or what might be called ideological neoliberalism, in ways that have undermined our political process and democracy itself.

Ideological neoliberalism depicted the transformation of industrial economies to service/knowledge economies as a progressive evolution — an inevitable and socially beneficial process that promised to be the wave of the future but instead gave us politically unsustainable levels of economic inequality. Similarly, neo-liberalism’s anti-government rhetoric militated against efforts to regulate technology industries and counter media consolidation, creating our current dysfunctional media landscape. In doing so, it glossed over whose interests were being served and what was being lost in the process, including the kinds of institutions that had historically contributed to strong working-class communities in large parts of the country. While Trumpism has tried to advertise itself to working-class whites as an anti-free market conservatism, its policies have mostly delivered more of the same — but who would actually know that, when bombarded with distorted news coverage?12

The future now hangs in the balance as the destabilizing forces unleashed by neoliberalism, including the undermining and/or hijacking of news outlets for working-class populations, continue to wreak havoc. We have travelled a long way from the newsstands of earlier generations in Southeast Chicago.

Suggested links

Christine Walley's MIT webpage

Exit Zero: Family and Class in Postindustrial Chicago

[1] Jack Metzgar in Striking Steel (Temple University Press, 2000 pg. 59) notes the wide circulation of Steelabor in steel-working communities in the 1950s, his sense that the union tried to convey sophisticated analyses of the state of steel markets and economics for the rank-and-file, and the ways that union shop stewards studied such analyses and then interpreted for other mill workers.

[2] While popular media narratives often attributed the victory of Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential election to white working-class voters shifting parties in the Midwestern “Rust Belt,” other commentators noted that Trump voters in the primaries who were classified as “working class” because they lacked a four-year college degree had median incomes of more than $120,000, at the same time that a larger number of white working-class voters in the industrial Midwest chose to sit out the election rather than switch parties (for overview see Christine J. Walley “Trump’s Election and the White Working Class: What We Missed,” American Ethnologist 2017, 44(2): 231-136). Over time, however, white working-class populations and some Latinos would shift towards Trump even if this was less a reality in 2016 than often assumed.

[3] Sherry Lee Linkon, The Half-Life of Deindustrialization, 2018, University of Michigan Press.

[4] Penelope Abernathy, The State of Local News 2022. (Medill School of Journalism report, Northwestern University, 2022).

[5] Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral, 2018, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science 359 (6380):1146-1151. The dynamics of media mis/disinformation have been discussed in many venues including the MIT Workshop “Democracy, Disinformation, AI, and Platform Regulation,” 1/28/21.

[6] No Longer Newsworthy: How the Mainstream Media Abandoned the Working Class, Christopher R. Martin, 2019, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

[7] Barry Bluestone and Bennett Harrison, The Deindustrialization of America (Basic Books, 1982); Christine J Walley Exit Zero: Family and Class in Post-Industrial Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 2013); David Bensman and Roberta Lynch Rusted Dreams (University of California Press, 1987); David Weil, The Fissured Workplace (Harvard University Press, 2014). Tellingly, during the 1980s and ’90s when U.S. steel mills were decimated, none closed across the Canadian border despite similar pressures, suggesting the importance of national outlooks; see Steven High, Industrial Sunset (University of Toronto Press, 2003).

[8] Although Rupert Murdoch bought the Chicago Sun-Times in 1984, he sold it two years later, while the planned 2018 merger between The Chicago Tribune and Sinclair Broadcasting (a group decried for passing questionable right-wing political commentary as “news” on local news stations) fell through. In addition, there have been intriguing media experiments in community-oriented local news like Block Club Chicago, albeit an outlet that like legacy news media is located behind a paywall which budget-constrained working-class residents who see free “news” readily available elsewhere may avoid.

[9] For discussion of Koch brother influence in pushing anti-regulatory, anti-union, and anti-climate action agendas see Christopher Leonard’s Kochland (Simon & Schuster, 2019) as well as Jane Mayer’s Dark Money (Anchor Books, 2017).

[10] Pew Research Center, Hispanic and Black News Media Fact Sheet, 7/27/21. Accessed online. Pew Research Center, “7 Facts about black Americans and the New Media,” 8/7/19. Accessed Online.

[11] Recognizing that “antiregulatory” can in practice mean re-regulating in ways that are favorable to certain businesses.

[12] For example, see discussion in Mayer (2017) of how Koch brothers’ proteges were central to the Trump administration despite their ostensible repudiation of Trump, as well as the reality of Trump’s tax and other policies, and the string of Ayn Rand devotees as political appointees.

Series published by SHASS Communications

Office of the Dean

Alison Lanier: Web Publishing; Senior Communication Associate

Leda Zimmerman: Principal Editor