THE HUMAN FACTOR

3 Questions with M. Amah Edoh

On Africa and Innovation

Photo by Jon Sachs / SHASS Communications

"Africa today is seen as the future of global innovation and entrepreneurship in areas from technology to the arts. Important questions about Africa’s new visibility include: Who is recognized as an expert? What is seen as innovative, and what knowledge is considered worth carrying forward?"

Science and technology are essential tools for innovation, and to reap their full potential, we also need to articulate and solve the many aspects of today’s global issues that are rooted in the political, cultural, and economic realities of the human world. With that mission in mind, SHASS Communications launched The Human Factor — an ongoing series that highlights humanistic research and the societal dimensions of global challenges. Contributors to this series also share ideas for cultivating the multidisciplinary collaborations needed to solve the major civilizational issues of our time.

M. Amah Edoh is an assistant professor Anthropology and African studies in the MIT SHASS-based Anthropology section. Her research centers on the “African print” or “wax" cloth textile — a particular variety of which Edoh uses as a lens for examining Africa’s place on the world stage. While wax cloth is seen by many as the quintessential marker of African cultural identity, it has a thoroughly global history.

Derived from batik, a Javanese manual textile printing technique that was mechanized in the late 19th century by Europeans, the material started being produced (in places like Holland and England) exclusively for West African markets at the turn of the 20th century. Today, the wax cloth made in Holland — known as "Dutch wax cloth," or just "Dutch wax" — is considered the most valuable variety of wax cloth in West Africa — especially in Togo, where Edoh conducts fieldwork. Edoh recently discussed Dutch wax cloth and the implications of her research with SHASS Communications.

•

What has your research into Dutch wax cloth revealed about the ways in which value and meaning are produced through the circulation of commodities across different regions of the globe?

Dutch wax cloth is a remarkable archive of West Africa’s engagement with the rest of the world, from the 19th century to the present. The cloth embodies the historical and contemporary contributions of social actors all along its trajectories — from the designs printed on the textiles to the ways the cloth is advertised, sold, and used — and pushes us to complicate our ideas about what makes an object valuable or meaningful.

For example, when people find out that this cloth that they’ve come to identify with Africa and African-ness is actually not indigenous to the continent, a common reaction is: well, in that case, it’s not really an African thing. But when you look at the distinctive and recognizable aesthetic of Dutch wax cloth — the fact that it is the product of exchanges over decades between Dutch designers and Togolese and other West African sellers and buyers of the cloth — you realize that this cloth has been made African through the intellectual, aesthetic, and emotional labor of West Africans.

West African women, in particular, made this cloth a high-value object through their enforcement of norms about how the cloth should or should not be crafted and by naming designs after popular expressions or current events. For instance, one design was named “Michelle Obama’s handbag” because the release of the print, which featured a purse, coincided with the Obamas’ 2009 visit to Ghana. This labor, along with that of a diverse cast of actors that includes textile designers, missionaries, and tailors, made Dutch wax cloth into “African print” cloth.

A textile retailer presents her fabrics in Togo. Photo: Alexander Sarley, Creative Commons

"The recent economic growth reported for the African continent belies sizeable inequalities within and across countries. How might we engineer the type of entrepreneurship that helps to close these gaps?"

From MIT OCW

Chalk Radio Podcast with Amah Edoh

What does “Africa” mean to the innovation economy today, and what practical lessons can would-be innovators draw from your research into craft practices in West Africa?

Long considered marginal to the global economy, Africa today is seen as the future of global innovation and entrepreneurship in areas from technology to the arts. That shift is reflected even here at MIT, in the call for a greater focus on Africa in MIT’s 2017 Global Strategy report. What I consider to be some of the important questions as we face this moment of Africa's new visibility are: Who is recognized as an expert? What is seen as innovative, and what knowledge is considered worth carrying forward? Who gets to be the face of this “New Africa”?

The recent economic growth reported for the African continent belies not only sizeable, but also increasing inequalities both within and across countries. How do we undertake projects in a manner that does not exacerbate existing inequalities, whether they be around class, age, sex, education level, nationality, or something else? Might we even engineer the type of entrepreneurship that helps to close these gaps?

In my research in Lomé, Togo, I’ve spent time with tailors who practice a Dutch wax cloth sewing technique that is falling into disuse. It is labor-intensive, and clients consider it old-fashioned (ñagankɔme, the name of the technique in Mina, Togo’s lingua franca, translates literally as “grandmother neckline”). And yet, it is an incredibly sophisticated technique in which tailors alter and adorn the cloth while minimizing cutting; because Dutch wax is considered so valuable, there has historically been a premium in Togo on maintaining the cloth’s integrity. In other words, this is a tailoring logic that is fundamentally conservationist, even as it serves the aesthetic and practical functions of dress. Such a conservationist ethos is more important than ever, as we keep looking for ways to preserve resources and reduce waste.

Because this sewing technique is undervalued in Lomé, the people who master it are typically women from very modest backgrounds. These women are experts, and we stand to learn much from them. Yet, by virtue of their class background (poor), age (older), sex (female), formal education level (low), or the fact that they live in a small, francophone country often overshadowed by heavyweight neighbors like Ghana, Nigeria, or Senegal, these women do not fit the expected profile of “experts.” How much knowledge are we missing out on every day that could benefit the world at large, simply because we look past people like these ñagankɔme tailors?

Photograph courtesy of Amah Edoh

"The people who master the ñagankɔme sewing technique are typically women from very modest backgrounds. We stand to learn much from them, yet they do not fit the expected profile of 'experts.' How much knowledge are we missing that could benefit the world simply because we look past people like these ñagankɔme tailors?"

President Reif has said that the solutions to today’s challenges depend on marrying advanced technical and scientific capabilities with a deep understanding of the world’s political, cultural, and economic realities. What barriers do you see to such multi-disciplinary collaborations, and how can we overcome them?

The ability to marry advanced technical and scientific capabilities with a deep understanding of political, cultural, and economic realities first requires valuing different forms of knowledge equally. This has implications for who we — those of us privileged to sit at highly resourced and prestigious institutions like MIT — invite to be at the proverbial table where solutions to existing problems are sought, or where what even constitutes a “problem” is investigated. In fact, it should push us to take the table into new spaces, to change the shape of the table — even get rid of the table entirely!

Further, interrogating our notions of what constitutes expertise or valuable modes of knowing or doing means broadening our sense of the forms that “solutions” might take. This goes for academic scholarship itself: We must expand our sense of what it can look like. I’m heartened by moves in the social sciences, for instance, to increasingly recognize non-text-based work — film, for example — on an equal footing with articles or dissertations, and again by new digital humanities initiatives right here at MIT, that bring together humanistic and coding expertise to tackle research problems.

Too often these days, including at MIT, the humanistic fileds (the social sciences, arts, and humanities) are considered secondary to technical fields. I have seen that throughout my years at the Institute, experiencing it firsthand as an undergraduate (in Course 17, political science) and as a graduate student (in the HASTS program). Now, as a faculty member, I hear from my students that this perception persists. Multidisciplinary approaches — which, as President Reif says, are essential for solving today's major issues — will require a profound commitment to flattening the hierarchy between different forms of knowledge and ways of knowing.

Suggested links

Amah Edoh

The Human Factor Series

Humanistic research on the societal dimensions of global challenges

MIT OCW: Chalk Radio Podcast with Amah Edoh

Department of Political Science

MIT-Africa Initiative

MIT HASTS

Doctoral program in History / Anthropology / Science, Technology, and Society

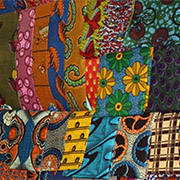

Detail, Wax Cloth Shop

Story prepared by SHASS Communications

Human Factor Series Editor: Emily Hiestand

Editorial Team: Kathryn O'Neill and Emily Hiestand