Research Portfolio | Language + Media

Why is Japanese anime a global hit?

Ian Condry, Associate Professor of Japanese Cultural Studies at MIT, cites creative collaboration as the key to anime’s worldwide popularity.

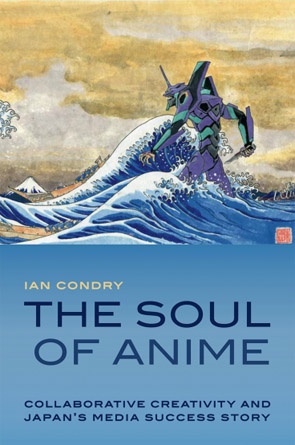

Japanese anime — animation, usually in the form of hand-drawn cartoons — is a wildly popular global export: According to one estimate, about 60 percent of the world’s animated television shows originate in Japan. They have become popular, as Condry asserts in a new book, The Soul of Anime (Duke University Press, 2013), by embracing what he calls “collaborative creativity” — by accepting input from a range of artists, and, crucially, feedback and modifications from fans. And when fans get involved, Condry says, it makes a pop-culture product, like a cartoon series, “a living thing for the people who are interested.”

Creativity, ‘Gundam’-style

While the origins of anime techniques are about a century old, the cartoons took hold in Japan only in the post-war era. Other global Japanese anime hits include the Pokemon series of video games, cards, cartoons and toys, which, as Condry notes, are “so ubiquitous, it’s kind of a shared language of youth.”

And yet, the success of Japanese anime constitutes something of a mystery. If you were to concoct a plan for entertainment-industry success in the digital age, Condry notes, it would probably not involve the painstaking development of hand-drawn cartoons.

“It’s incredibly difficult, and not very lucrative” for the artists, says Condry, who visited dozens of anime studios, workshops and artists while researching the book over the last eight years. “It’s one of the most labor-intensive forms of media there is.” Entertainment companies do not necessarily make huge profits off anime, which was an issue motivating Condry’s study; as he puts it, “How can things that don’t make money go global?”

The answer is that anime producers create many series and watch closely for what catches on — and then, once the characters in a series become a “platform” for audience participation, may cash in through toys, games and other forms of entertainment.

“What distinguishes anime,” Condry says, “is the degree of openness the copyright holders have to give the fans a chance to re-work the characters” and other elements of the original cartoons. He adds: “The ‘Gundam’ producers, when shown work created by fans, just said, ‘That might be the way it is.’”

Getting more social

One historical curiosity of anime, Condry notes, is that the dynamics making it successful emerged even prior to the commercialization of the Internet and the rise of social media, which in theory should make mass collaboration, today, easier than ever.

Indeed, it is possible that the history of anime, Condry says, holds “lessons we might use for new emergent industries” that can tap into crowdsourcing and collective feedback. As such, Thomas LaMarre, a scholar of Japanese culture at McGill University in Montreal, calls the book “a bold challenge to our understanding of the social side of media.”

And while anime might be a globally exported product, audience participation also makes it a highly personal form of entertainment, Condry adds. Anime might often feature seemingly soulless robots and monsters, but the “soul” of the art form, as Condry sees it, precisely comes from the investment of creative energy that its fans pour into it.

“Anime is imbued with a sense of social energy,” Condry says.

— excerpted from MIT News story by Peter Dizikes