Cuthbert receives $500K Digging into Data grant

for innovative musicology research

“Myke is a pathfinder through the

emerging world of digital humanities."

— Janet Sonenberg, Head, MIT Music and Theater Arts

New ways of studying music

Michael Cuthbert, the Homer A. Burnell Career Development Professor and Associate Professor of Music has been awarded a $500K grant from the Digging into Data consortium. The grant, given to Cuthbert in concert with an international team of researchers, supports his work using computational techniques to study changes in Western musical style.

Cuthbert said he was “ecstatic” when he heard the news. “I've already been working on some parts of the project, and knowing that I will now have the support to complete it is a great boon."

He will receive roughly $175,000 specifically for his music21 project as a winner of the Digging Into Data Challenge grant competition, through which the NEH awarded $4.8 million to teams investigating how computational techniques may be applied to the massive multi-source datasets made possible by modern technology.

A humanist with technical acumen

“Myke is a pathfinder through the emerging world of digital humanities. In my opinion he is a visionary,” said Janet Sonenberg, a professor of theater arts and Head of the Music and Theater Arts Section. “He is a humanist who has the technical acumen to lead this project from great idea to successful realization."

Digital humanities at MIT

The School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences is home to several cutting-edge projects that emphasize digital humanities, an area of scholarship that uses computer technology to enhance humanities research—for example by digitizing and analyzing documents. These include "Global Shakespeare," an archive of Shakespeare performances, and "Visualizing Cultures," an effort to explore the potential of the Web for developing innovative image-driven scholarship and learning. Several programs fall under the aegis of HyperStudio: The Laboratory for Digital Humanities at MIT.

The ELVIS project

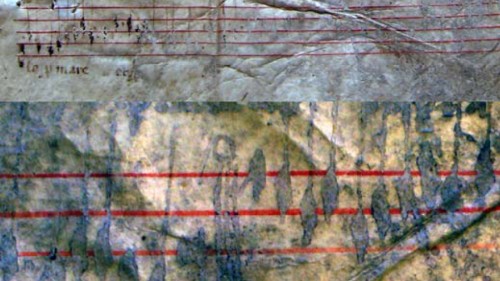

The funding for music21 is included as part of the major grant to a larger team project called “Electronic Locator of Vertical Interval Successions (ELVIS): The First Large Data-Driven Research Project on Musical Style,” which will look at changes from 1300 to 1900 using the digitized collections of several large music repositories.

ELVIS will specifically investigate how the use of vertical intervals (chords, essentially) has changed during this 600-year period, Cuthbert said. “To make this project work we need two things: 1) a huge collection of music encoded in a way computers can read it, and 2) software tools for managing these collections. The music21 toolkit supplies these tools.”

music21 is Cuthbert’s MIT research lab and a project that combines

tools of computer programming and musicology to create new tools

for music research and analysis. At MIT, he says, students in every

discipline have profound opportunities to contribute to research in

music and history. Science majors can use chemical analyses of ink

content on medieval manuscripts. Economic models can apply to

musical patronage.

music21

Developed by Cuthbert with Visiting Assistant Professor Christopher Ariza beginning in 2006, music21 is a suite of tools for computer-aided musicology. By simplifying the programming tasks needed to work with musical scores, it allows scholars to quickly and simply answer such questions as: How common are certain pitches in a Chopin Mazurka? and, How closely does the spacing of notes in the music of Aaron Copland approximate the spacing of overtones in the harmonic series?

Cuthbert created the program to help him answer his own research questions concerning how European musical styles evolved in the early 14th and 15th centuries, and it has been extraordinarily successful, with courses now taught in music21 at three universities. “It has become the de facto standard for software music analysis” Cuthbert said.

A suite of tools

However, Cuthbert said it’s important to note that the program is more of a suite of tools than an off-the-shelf solution. “It’s not something you download and hit ‘run’ and it does something for you,” he said, remarking that this is a common misconception among those he speaks to about the program. “You need some programming skills to be able to use this. But, it takes tasks that might take a programmer 200 hours and reduces them to two hours.”

An analogy would be using prefabricated components—such as cabinets, drawers, and shelving—to create a kitchen vs. building one directly from raw materials. “What we’re trying to do is make bigger and bigger prefab pieces as we go. Chords are the main focus of ELVIS project, so we’ll be doing more with that,” Cuthbert said.

Cuthbert immerses himself in 14th century music history

because “some of the most beautiful, strange, and

undiscovered music is there." Music history, he says,

also offers MIT undergraduates the chance to learn

independent research skills that will serve them well

in their lives as scientists and engineers.

Increasing the speed and capacity of music21

The ELVIS team—which includes members from Canada and the United Kingdom in addition to Cuthbert and a colleague at Yale University—has already created a database of approximately 900,000 pieces of music. Much of the grant money will be used to make music21 work faster in order to examine the massive amount of data, Cuthbert said. “Now [music21 tools] can analyze 1,000 pieces in an hour, and we’re looking to do 10,000 or 1000,000,” he said.

“MIT is a great place to do this work, because there are ideas students have that I can immediately put in,” Cuthbert said. “Colleagues from CSAIL and other areas have also suggested improvements. It’s a great environment.”

In addition to the funding from NEH, Cuthbert’s esearch has been supported with three grants totaling $325,000 awarded by the Seaver Institute.

entry from Cuthbert's blog

Changing Musical Time in the Renaissance (and Today)

The concepts of time, rhythm, and musical notation have changed dramatically from the Middle Ages to the Present. Music has slowed dramatically over the past millennium, and composers have repeatedly taken advantage of new resources. This pre-print of a short paper in honor of Joseph Connors documents this change and shows how it can affect how we think of nearly every piece written from 1100 to today.

Suggested Links

Music Program

MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

Cuthbert's Web Page

Faculty Bio

Michael Cuthbert

State of the Art: Continuum

Feature article in Soundings Magazine

Listening Faster

How Digital Humanities is Transforming Music Scholarship

Digital Humanities 2.0

Series in The New York Times