A Postdoc Chemist Encounters Philosophy at MIT

On studying with Thomas Kuhn and Sylvain Bromberger

Commentary by Jeffrey H. Toney, PhD

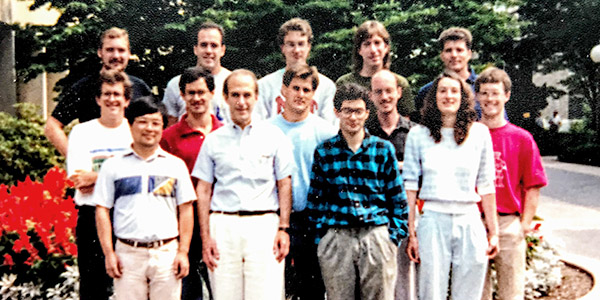

MIT Lippard Group, August 1989; Dr. Toney is in the second row, fourth from left

"Collaborating with the professors and students in this philosophy class made the deepest impression on my understanding of my role as a scientist to challenge established ways of thinking. But the class gave me even more than that: it somehow gave me the courage to take the risk of trying seemingly impossible approaches to solving problems."

— Jeffrey H. Toney, provost and vice president for academic affairs, Kean University

Jeffrey H. Toney, PhD, is the provost and vice president for academic affairs at Kean University as well as an author—both of scholarly scientific articles and of popular commentaries. Recently, Toney shared his reflections on the time he spent as a postdoc at MIT in the late 1980s, when he discovered that philosophy could be as interesting as his main area of research: chemistry.

• • •

MIT prepares scientists, engineers, and problem-solvers of all kinds in surprising, delightful ways. I was privileged to join MIT in 1987 as a postdoc in the Department of Chemistry, supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant. Being part of a world-renowned research group, mentoring undergraduate and graduate students, and having access to the Institute’s vast resources and the culture of Cambridge and Boston was a dream come true.

As the first in my family to attend college, I was driven to prove that I belonged at MIT. I could have devoted each waking hour to working in the chemistry lab and diving into the scholarly literature, but I also wanted to take in everything MIT offered.

New ideas about science itself

My first transformational experience at MIT began when I took “Topics in Philosophy of Science,” a course co-taught by Thomas S. Kuhn and Sylvain Bromberger, two of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century. Our class of about 15 was a collection of undergraduate and graduate students from the School of Science, the School of Engineering, and the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.

As a chemistry postdoc, I may have been the most unprepared student in the class. I had completed only one related course as an undergraduate, on theology, ethics, and medicine. I had, however, read Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, which astounded me by presenting the idea that scientists can be resistant to change. Kuhn showed that the scientific community has a history of pursuing experiments that will explain and further support well-established models, rather than creating new models or ways of thinking. It is the rebels, the fearless, that let the data lead them into unchartered territories.

I wondered if Kuhn’s ideas would apply to my own research, and I was delighted when he welcomed me to audit his class. In advance, I began some of the readings: J.S. Mill, A System of Logic; William Whewell, Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences; David Wiggins, Sameness and Substance. This was a different language. I had to look up many, many terms — less reading than deciphering. I began to question this whole thing. I thought perhaps I needed to focus on more “important” things — the experiments and data that NIH was paying me to complete.

"Every scientist is challenged with understanding our world, and how we ask questions has a major impact on how we design experiments to test our ideas. After this philosophy course, my approach to the scientific problems I was wrestling with as an MIT postdoc became much broader."

— Jeffrey H. Toney, provost and vice president for academic affairs, Kean University

Challenging questions and collaboration

For a time, I put the course readings away on a shelf. Then, a couple of weeks later, I decided to return to the “Kuhn stack.” Before the first class, I reread his book and then the course syllabus, which is when I came upon the following statement, referring to David Wiggins’ Sameness and Substance:

“This is much the most difficult reading to be faced during the semester. Those without background in philosophy are likely to feel lost the first time through, and even those with background will have trouble. Part of the difficulty is intrinsic to the material, but Wiggins adds to it by slipshod presentation. Don’t worry! There will be significant take home for all.”

That passage gave me confidence that I could take the class and contribute something meaningful. In any event, Kuhn had said that a seemingly failed experiment could end up being the one that changes people’s thinking. I dove in, and toward the end of the course, Kuhn handed out assignments that included this stunning confession, an exemplar of humility that was unimaginable to me coming from such an icon in philosophy:

“Approaching this material and these questions, we are all amateurs in one way or another. None of us is equipped to lecture, and none is going to do so. Come expecting to collaborate.”

We are all amateurs in one way or another. Wow! If Professors Kuhn and Bromberger could feel that way, what did it mean for me and my classmates? Perhaps the declaration that you’re an amateur, like everyone else, liberates us to explore, take chances, and fail — making us stronger, better versions of ourselves.

A deeper understanding of the role of science

Collaborating with the professors and students in this class made the deepest impression on my understanding of my role as a scientist to challenge established ways of thinking. But the class gave me even more than that. In an odd way, I think it somehow gave me the courage to take the risk of attempting seemingly impossible approaches to solving problems.

Every scientist is challenged with understanding our world, and how we ask questions has a major impact on how we design experiments to test our ideas. After this course, my approach to the scientific problems I was wrestling with as an MIT postdoc became much broader.

Thank you, Professors Kuhn and Bromberger, for inspiring me to think boldly and ask crazy questions, and to Professor Stephen J. Lippard for the opportunity to work in his research group. I only wish that I could have shared this gratitude in person, for experiences at MIT that established a habit of mind that has, over the years, kept me hungry to take on new challenges far beyond science.

Biographical note

Jeffrey H. Toney has a BS in chemistry from the University of Virginia and an MS and PhD in chemistry from Northwestern University. He served as an NIH Postdoctoral Research Fellow at MIT from 1987-1989, and worked at Merck Research Laboratories before going into academia. He joined Kean University in 2008 as dean of the College of Natural, Applied and Health Sciences, and has served as provost and vice president for academic affairs since 2013.

Suggested links

Tribute to Sylvain Bromberger

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn