THE MEANINGS OF MASKS

Venetian Masks | Jeffrey S. Ravel

for Carnival — and for finessing an archaic political order

Detail, Conversation between Baute Masks, by Pietro Longhi (1701-1785); Museo Del Settecento Veneziano

"By the eighteenth-century in Venice, people had grown accustomed to wearing masks in public perpetually, not for health reasons but for social and cultural ones. Furthermore, the Venetian state actually required its citizens and visitors to the Republic to don masks in many public spaces."

SERIES | THE MEANINGS OF MASKS

As The Washington Post has reported, "at the heart of the dismal US coronavirus response" is a "fraught relationship with masks." With this series of commentaries — inspired by ideas from literature profressor Sandy Alexandre — MIT faculty explore the myriad historic, creative, and cultural meanings of masks to offer more ways to think about, appreciate, and practice protective masking — currently a primary way to contain the Covid-19 pandemic.

• • •

MIT professor of history Jeffrey S. Ravel studies the history of French and European political culture from 1650 to 1850.

Q: Humans use masks for a variety of purposes, ranging from protection to play to artistic performance. Can you provide some examples of masks and masking drawn from your field of early modern European history?

Ravel: In Early Modern Europe (roughly 1400-1800 CE), masking most frequently occurred during Carnival, a period of raucous celebrations in February or early March that immediately preceded Lent, the six-week period of fasting and penance that culminated in Easter Sunday. While Carnival traditions are most closely associated with Roman Catholic communities on the European continent, they also occurred in areas populated by Protestant majorities. Public celebrations in streets and market places featured singing, dancing, drinking, courting, and other boisterous and sometimes lewd or unsavory behaviors.

Masking was a common aspect of Carnival everywhere at this time. Unlike the masks which cover our noses and mouths today, Carnival masks most often obscured the forehead and cheekbones, and left the nostrils and mouth exposed. Some masks covered the entire face. At first glance it would seem that the purpose of these masks was to provide wearers with anonymity, so that they could engage in excessive revelry without damaging their standing in the community or jeopardizing their chances of salvation in the eyes of the Church.

In most instances, however, neighborhoods were small and their inhabitants’ voices and postures were known to each other, so that the masks only provided the illusion of anonymity. If masks did not truly hide identity, therefore, why wear them?

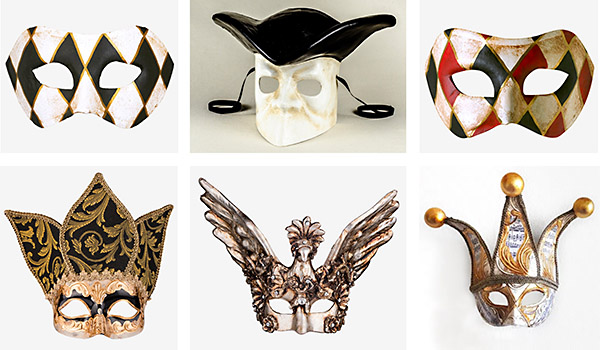

Some examples of Venetian Carnival Masks; the upper middle mask is a Baute mask, worn beyond the Carnival season for various social and political occasions.

"Masking...had become a way to allow Venetians of all classes to intermingle socially, economically, and culturally for a large part of the year without calling into question the archaic political order, and it also allowed those from different socio-economic groupings in search of love and physical intimacy to encounter each other in public spaces."

In a striking analysis of Venice in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Boston University historian James H. Johnson has provided a more nuanced interpretation of the Early Modern use of masks.* By the eighteenth century, mask-wearing among all classes and genders extended from Carnival through the summer, lasting half the year. Venetians not only wore masks during the week of Carnival, they continued to wear them through Lent and beyond at the theater, in gambling halls and brothels, and in public marketplaces and private homes. Foreign ambassadors and state officials, including the Doge (the head of the Venetian government), wore them during public ceremonies and private meetings and negotiations.

Johnson argues that Venetian masking served a conservative social function, rather than a progressive political or public health one. Venice’s patrician caste, i.e., those who enjoyed the privilege to participate in the city-state’s political affairs, had been set at a severely limited number of families in 1297. Over the next five centuries, the numbers of this selective political class fluctuated slightly, but remained a miniscule percentage of the total population. As time passed, however, through commerce, manufacturing, and political favor, other families grew rich, and some of the original patrician clans declined. By the eighteenth century, social realities did not correspond to the socio-political categories established five hundred years earlier.

Masking, Johnson argues, had become a way to allow Venetians of all classes to intermingle socially, economically, and culturally for a large part of the year without calling into question the archaic political order, and it also allowed those from different socio-economic groupings in search of love and physical intimacy to encounter each other in public spaces. The patrician class, masking, and Venetian Republicanism were all abolished in 1797 when Napoleon Bonaparte conquered the Serene Republic and enforced the egalitarian principles of the French Revolution.

Jeffrey S. Ravel, MIT Professor of History; photo by Jon Sachs

"Early Modern maskers, and especially the Venetians who inhabited their masks half the year, were far more adept at social interactions while masked than we are. Since it is likely we will all be wearing our masks for quite a while, we will need to develop ways to overcome this pandemic-imposed impediment to sociability."

Q: What are the similarities and differences between masking in eighteenth-century Venice and masking today?

Ravel: The Venetian case has some parallels with our masking practices today. By the eighteenth-century in Venice, people had grown accustomed to wearing masks in public perpetually, not for health reasons but for social and cultural ones. Furthermore, the Venetian state actually required its citizens and visitors to the Republic to don masks in many public spaces. We are experiencing similar state-mandated requirements for masking today. In contrast, though, the masks we put on are intended to control a pandemic that — as of this writing in early September 2020 — has killed at least 900,000 people world-wide, and over 192,000 in the United States. Our protective masks are not designed to provide anonymity, its illusion, or to preserve the social order; rather, medical science tells us that they will help substantially slow the transmission of a disease for which there is no man-made cure.

Nevertheless, our masks have secondary consequences that manifest themselves daily. My anthropologist colleague Graham Jones has written eloquently elsewhere on this site about the partisan political meanings of mask-wearing in the United States, and the resonances of breathing, being and racism in this country. I agree with his analysis; I also find myself speculating on the way that our mundane daily interactions are transformed by the presence of masks.

Early Modern masks allowed wearers to breathe more freely, and called attention to the twinkle of the eyes or their subtle grins or grimaces. But the many ways we have today of communicating verbally and non-verbally are suppressed by our public health needs. Something is lost when we need to tell people that we are smiling at them. And the risk of social confrontation becomes greater when we cannot clearly read facial signals from others that indicate anger or disgust. Early Modern maskers, and especially the Venetians who inhabited their masks half the year, were far more adept at social interactions while masked than we are. Since it is likely we will all be wearing our masks for quite a while, we will need to develop ways to overcome this pandemic-imposed impediment to sociability.

One of several artisan mask workshops in Venice

"A number of years ago I had the chance to visit modern-day Venice; sadly, I was not there during Carnival. But those who have visited the contemporary city know that in addition to several artisan workshops that produce traditional Carnival masks in authentic materials, there are also tourist shops hawking masks on every corner."

Q: What is your favorite mask? Why does it appeal to you?

Ravel: A number of years ago I had the chance to visit modern-day Venice; sadly, I was not there during Carnival. But those who have visited the contemporary city know that in addition to several artisan workshops that produce traditional Carnival masks in authentic materials, there are also tourist shops hawking masks on every corner. I wandered into one and purchased a monochrome brown mask that resembles the one worn by the commedia dell’arte character Pulcinella. It covers my eyes and features an over-sized nose that juts out a good half a foot from my face. The mask sits on the windowsill in my MIT office, where anyone who comes to visit can see it. It has been there for years, but interestingly no one has ever commented on it. Perhaps they suspect that I am prone to indulging in imposture, but are too polite to call me out!

* James H. Johnson, Venice Incognito: Masks in the Serene Republic (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011).

___

MIT professor of history Jeffrey S. Ravel studies the history of French and European political culture from 1650 to 1850. His teaching interests include Old Regime and Revolutionary France, European cultural and intellectual history, the history of the book and comparative media studies, and World history. Ravel is the author of The Would-Be Commoner: A Tale of Deception, Murder, and Justice in Seventeenth Century France (Houghton Mifflin, 2008); and The Contested Parterre: Public Theater and French Political Culture, 1680-1791 (Cornell University Press, 1999). He co-directs the collaborative Comédie-Française Registers Project and is currently at work developing the Visualizing Maritime History Project.

Suggested links

Jeffrey Ravel's MIT webpage

MIT History

A Guide to the Masks of Venice

Books:

The Would-Be Commoner: A Tale of Deception, Murder, and Justice in Seventeenth Century France (Houghton Mifflin, 2008)

The Contested Parterre: Public Theater and French Political Culture, 1680-1791 (Cornell University Press, 1999)

Digital Humanities Projects:

Comédie-Française Registers Project

Visualizing Maritime History Project

Stories:

In the MIT History Workshop | Building a printing press illuminates human systems

A group of MIT students briefly put away their cell phones this spring to concentrate on a much older information storage and retrieval device: the book. As students built a handset printing press — the kind of press on which the documents of the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution were printed — they also gained insight into human systems.

Story

Ravel awarded grant from National Park Service for Visualizing Maritime History project

The National Park Service, with the Maritime Administration, announced the award of a $50,000 grant in support of the Visualizing Maritime History Project, led by Jeffrey Ravel, MIT SHASS Professor of History.

Story

Computing and AI | Perspectives from history by Jeffrey Ravel

"The nuanced debates in which historians engage about causality to provide a useful frame of reference for considering the issues that will inevitably emerge from new computing technologies. This methodology of the history field, and an appreciation of the past, are opportunities to imagine our way out of today’s existential threats."

Commentary

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Series Editor and Designer: Emily Hiestand

Consulting Editor: Kathryn O'Neill

Published 9 September 2020