MEDIA AND THE PANDEMIC

CNN and Sesame Street team up on Town Halls for kids

MIT media scholar Heather Hendershot and children's literature scholar Marah Gubar discuss programs on the pandemic, racism.

L to R: MIT Professors Heather Hendershot and Marah Gubar

"I'm interested in thinking about the town halls as media events and, more specifically, as political media events. Cable news is so polarized right now, and when you deal with kids and anything with political dimensions, it’s sort of inherently a hot potato situation."

— Heather Hendershot, Professor of Comparative Media Studies

INTRODUCTION

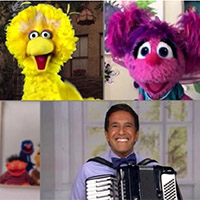

On April 25, 2020, CNN aired a coronavirus town hall, a one-hour TV special aimed at parents and children. The cable news network partnered with Sesame Street on the show, which was hosted by CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta and Erica Hill and featured Muppets such as Elmo, Big Bird, and Grover. On June 13 they continued the experiment with their ABC’s of Covid-19 town hall. In between, on June 6, CNN partnered with Sesame Street again on “Coming Together: Standing up to Racism.”

I recently invited Professor Marah Gubar to join me in a conversation about the Covid-19 specials, with the racism episode providing some additional context. Professor Gubar is on MIT’s Literature faculty and is the author of Artful Dodgers: Reconceiving the Golden Age of Children’s Literature, which won the Children’s Literature Association Book Award. More recently she wrote Seen and Heard: Remembering Children’s Art and Activism.

— Heather Hendershot, MIT Professor of Comparative Media Studies

• • •

This conversation has been edited for length. Click here for the longer version.

Hendershot: I thought we could open by explaining why we’re interested in these CNN–Sesame Street specials. I’ll start by saying that, first, I’m interested in the town halls as media events and, more specifically, as political media events. Children’s TV has never been an apolitical realm — lots of shows contain “pro-social” messaging about basic issues like how to be a good friend or valuing diversity.

But it’s obviously potentially more controversial to take on tough issues in a nonfiction context like the news. CNN was going out on a limb a little bit, and it could have backfired, but it didn’t. Second, I’m interested in the town halls because I started my career researching children’s media (especially network and cable TV), and I have an ongoing interest in the ways that adults imagine and construct an idealized child through their media creations.

Gubar: As someone who works in the interlinked fields of children’s literature and childhood studies, I’m interested in how adult ways of portraying and engaging with children have shifted over time and across cultures. So, I’m coming at it more from an interest in thinking about how Sesame Street and children’s television programs have changed over time. I think it’s really fascinating to compare the way Sesame Street functions today to what it was like in the 70’s when the show first emerged.

Hendershot: I agree. Sesame Street premiered in 1969 and was pretty radical at a time when the landscape of “educational” children’s television was slim. They undertook serious curriculum development for three-to-five year olds, and on a really high budget, and also had a political agenda about racial diversity and tolerance and picturing inner-city kids for the first time.

Gubar: In the early episodes, it’s really powerful how the street itself looks genuinely gritty, like a real city street, and the opening credits show kids in an urban playground. And I love that Sesame Street was a collaboration between academic experts in child development and people with commercial media experience. Plus, the show was influenced by MLK’s vision of a “beloved community” where poverty and prejudice aren’t tolerated. And it was partly publicly funded by government grants, to help level the playing field for disadvantaged kids who didn’t have access to preschool. It was so progressive.

"As someone who works in the interlinked fields of children’s literature and childhood studies, I’m interested in how adult ways of portraying and engaging with children have shifted over time and across cultures."

— Marah Gubar, Associate Professor of Literature

Hendershot: It’s a landmark show on so many levels, and a strong partner for this kind of difficult programming. What are some of your immediate impressions of the CNN-Sesame Street town halls?

Gubar: I liked the Covid-19 specials more than the racism special, because the Covid-19 specials did a better job incorporating Sesame Street’s ethos. The whole idea that “we’re all in this together” and we need to take care of each other is such a core part of Sesame Street, a show that asks: “What does it mean to be a good neighbor?” The Covid specials really worked well with that, advancing the idea that when we take care of ourselves by wearing a mask, we’re also taking care of others. This idea was so beautifully expressed in the song “Like Birds of a Feather. We're in this together.”

Hendershot: Yes! I loved that song too, and I agree about the value of the informational material. At one point a child asked about being safe and one of the adults answers, you know soap is for the outside but not for the inside and is really emphatic about never swallowing anything like soap. This is perhaps the closest that the Covid-19 town halls come to acknowledging the current political situation, don’t you think?

Gubar: Right — do not drink soap, detergent, or bleach. That should not have political resonance, but obviously it does at this moment.

Hendershot: They obviously didn’t need to say “the president suggested you should swallow bleach, but don’t do it.” They didn’t go there, and that was absolutely appropriate. Did you feel there were any moments where it would have been appropriate to include some kind of political angle in the conversation?

Gubar: Well, I noted that same moment when they did not mention the president, and I also thought that was fine. It was clear to grown-up viewers what the reference point was. I guess I didn’t think that they ought to have engaged in politics more, or notice them ostentatiously avoiding it — except for that moment about not swallowing poison. Did you?

Hendershot: There was a tricky moment in the June 13 town hall when a child asked a health department official, I see people outside all the time, but we’re not supposed to go outside. So how come they can go out and I can’t? And the official responded in a very careful way: “Well, you have to remember that every family has different rules and that places have different rules. People obey the rules of their family or their place, and so what’s important is what you decide in your family.”

That was a moment of perhaps dropping the ball, given that what Sesame Street is so good at—and what CNN taps into with the concept of a town hall—is thinking about community. Was there a way to explain that people and places have different rules, but not everyone is following the rules? CNN is saying “we’re all in this together” without acknowledging that perhaps some people are not fully embracing the idea of community.

Gubar: It does seem like a lost opportunity because it would not have been that hard to have, for example, a conversation between two Muppets where one says, “Well, I’m not gonna wear a mask!” and then a discussion could have ensued. That would have been in keeping with the spirit of Sesame Street, since its characters work out disagreements and misunderstandings all the time.

"I liked the Covid-19 specials more than the racism special, because the two Covid specials did a better job incorporating Sesame Street’s already existing ethos. The whole idea that we need to take care of each other is a core part of both Sesame Street and Mister Rogers, two shows that address the same question: 'What does it mean to be a good neighbor?'"

— Marah Gubar, Associate Professor of Literature

Hendershot: There’s actually only limited interaction between the Muppets throughout the town halls, which struck me as a bit strange. Also, I would have liked to have heard more from children. And along those lines, here’s where I’d like to hear a little about why you thought the Covid-19 town halls were stronger than the anti-racism town hall.

Gubar: My main feeling about the racism town hall was that they kept making it a personal problem rather than acknowledging the systemic nature of racism, as if all we need to do is change the hearts and minds of some problematic individuals, as opposed to collectively committing ourselves to ending inhumane policies and practices that harm some groups more than others.

Hendershot: So you would say that although the “ABCs of Covid-19” town hall doesn’t get into some political issues that it could have, the sense of community is very strong, in contrast to the individualizing impulse in the racism town hall?

Gubar: Exactly. They did not treat racism or policing as a neighborhood problem. Of course, structural racism isn’t always easy to explain or acknowledge. But the kids’ questions were so much bigger and more complex than the way they were answered, as was the moving song that twelve-year-old Keedron Bryant sang about trying to live in a society that’s proven so deadly to other Black boys.

Hendershot: That’s a really good point. The Covid questions were difficult, but the racism questions were even harder, and there was a bit more evasion there and deflection by the adults.

"What you’re pointing to is the difference between the network era and a post-network cable era and an era of social media, where everything is fragmented. The evening news offered a collective (if imperfect) shared sense of reality. There’s a nostalgia for the collectivity inherent in that, but then there’s the reality that it is not completely unattainable today, right? I think CNN has tapped into that in some ways with all their town halls."

— Heather Hendershot, Professor of Comparative Media Studies

Gubar: I appreciated when the adults didn’t offer an overly simple or evasive answer to tough questions, as when they said, about Covid-19, “we don't know when it’s going to be over.” With what’s happening in the U.S. right now, modeling epistemic humility has become, in itself, an implicit critique of the president’s discourse.

Hendershot: Yes. That’s something that we see in the town hall about racism too, where empathy becomes a key issue. One of the refrains about our president is that he seems incapable of empathy, and specifically around Black Lives Matter and Covid-19 issues. So when CNN shows an anti-bullying segment about empathy, they are implicitly doing something political. Overall, it’s impressive that these town halls really attempt to undertake a public service function. That was the remit of television news during the network era, and that’s generally not what cable news is today.

"Overall, it’s really interesting and impressive that CNN tried to do something that they considered sort of neutral, with these Covid town hall specials. CNN has a liberal orientation...and their Covid coverage has political dimensions, but the Sesame Street town halls really attempt to be neutral and undertake a public service function....These Covid town halls are very of the moment but also feel evocative of a past sense of TV news’ public service mission."

— Heather Hendershot, Professor of Comparative Media Studies

Gubar: Definitely. And this reminds me of what we were saying earlier about Sesame Street being partly publicly funded and conceptualized for the public good. I was just reading about the loss of the nightly network news that everybody used to watch and how that contributes to people being atomized in their separate media bubbles.

Hendershot: What you’re really pointing to is the difference between the network era and today’s fragmented cable and social media environment. The evening news offered a collective (if imperfect) shared sense of reality. We don’t want to be too nostalgic about it, but there was at least a real attempt, in theory, to speak to everyone. CNN has tapped into that in some ways with all their town halls, not just the ones for kids.

I’d add, too, that when Black Lives Matter demonstrations erupted in the days following George Floyd’s death, the networks weren’t running the footage 24/7. But on CNN you could watch live coverage and feel others were watching too. There’s a potential feeling of collectivity in that, which is also inherent to the very notion of programs designated as “town halls.”

Gubar: Yes, and that’s the whole refrain of these CNN-Sesame Street collaborations. We’re all in this together.

Suggested Links

The longer version of this conversation

Gubar's MIT webpage

MIT Comparative Media Studies