A swashbuckling play of ideas

Making "The Tragedy of Thomas Hobbes"

A collaboration between MIT Theater & the Royal Shakespeare Company

London 2008

In November of 2008, members of London’s Royal Shakespeare Company premiered a play first conceived in the minds of MIT Theater students and faculty, and written by a cutting-edge New York City playwright. "The Tragedy of Thomas Hobbes” is a swashbuckling play of ideas — featuring characters real (Thomas Hobbes, Robert Boyle, Oliver Cromwell) and imagined (Rotten and Black, two out of work actors). Its raw material—the pitched battle among the great minds of 17th-century Europe for the prize of uncovering what is real and true—is the stuff of science and art.

Whose version of the truth is right? — and other questions

“Whose version of the truth is right? And who gets to author scientific truth?” are questions raised by the play, says Janet Sonenberg, Professor of Theater Arts, and Head of the Music and Theater Arts Section.

These questions first began to take shape in a cross-disciplinary seminar for MIT undergraduates, team-taught by Sonenberg and Professor of Literature Diana Henderson. The students spent a term immersed in the culture wars (religious, political, philosophical and scientific) that raged during “the time of silence,” when the Puritan parliament shuttered all the theaters in England.

Out of that work, students developed research briefs and dramatic writing for Adriano Shaplin, the NYC playwright who taught the students about theater, even as the students taught him about science. Shaplin then spent three years writing the play and staging segments of the work with actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company.

A natural for MIT | exploring the wellsprings of experimental science

Once the production of the play with its razzle-dazzle of language and ideas was announced, many took it as logical, even inevitable, that such a play—plumbing the wellsprings of experimental science—should emerge from the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. Still, they wanted to know "How exactly did that happen?”

The Royal Shakespeare Company was attracted by the phenomenon of a world-class humanities and arts program in the context of a great scientific institution.

Origins in Cambridge and London

The tale embodies much of the story of the arts at MIT, and the reasons a great technical institute is committed to teaching the arts and humanities.

“The Tragedy of Thomas Hobbes” got its visible start in the freeform, rigorous atmosphere of the actual seminar (“Learning from the Past: Drama, Science, Performance”) taught by professors Sonenberg and Henderson, who between them form a mini-academy of literary and dramatic scholarship and performance expertise, and who share an interest in the clash and intersection of ideas.

But the ground for the venture was being cultivated long before. By the 1990s, word of the School’s enterprising theatrical work had made its way to the Royal Shakespeare Company. Though best known for its staging of historic and classic works, the Company was entering into a new era, which included a growing interest in the role of science in transformation and communication—drawing science into the realm of the arts—and using technology for new forms of theater.

The School and the Royal Shakespeare Company

“The roots of the MIT and RSC project were back sometime between 1999 and 2000 when the Royal Shakespeare Company approached MIT,” remembers Professor Henderson. “They had heard about MIT of course—and learned of Peter Donaldson’s online Shakespeare Archive, a premier attempt to do digital Shakespeare—and were interested in a new vision of technology and some form of collaboration.” MIT Corporation Chairman Dana Mead introduced the two organizations, and Associate Provost Philip Khoury (then Dean of the School), supported a collaboration.

In 2000, a flotilla of RSC luminaries—Adrian Noble, artistic director at the time; Michael Boyd, assistant artistic director, and Tom Piper, its visual designer—came to MIT. The RSC visitors were attracted by the intellectual fire-power of the faculty and by the phenomenon of world-class humanities and arts disciplines taught in the context of a scientific institution. The RSC leadership saw the school as a laboratory for the formulation and dramatic presentation of great ideas.

Possibilities began to bubble in this fertile meeting space for art and science, and a transatlantic schmooze commenced between the Royal Shakespeare Company and the School’s Theater Arts faculty. The growing friendship cultivated trust and affiliations that buoyed the project onward.

“You could feel your brain growing! You can’t

A Eureka Moment

Enter Janet Sonenberg and her Eureka moment. One day in 2002, she turned to Michael Boyd and said, “What would you think about a new play set during the Time of Silence, exploring the connection between the closing of the theaters and the beginning of experimentation in science?” Professor Sonenberg was referring to the time in English history (1642–1660) when parliament closed all the theaters in the land, leaving the public deprived of its customary performance and spectacle. During this same era—indeed, as though in a play—radical scientists were challenging the old order of natural philosophy; their investigations required public experiments.

“The idea for the play came from years of teaching at MIT and thinking about the performative nature of experiments...and scientists,” says Sonenberg.

Building knowledge on facts | a revolutionary idea

“Theater and sermons were the main media of that era, in much the way we’re so visually attuned today because of film and TV,” she says. “Earlier scientists, including Thomas Hobbes, were still reasoning from first principles, logic that had passed down from the scholastics. The younger scientists rejected these notions; ’let us build our knowledge based on facts’ was their revolutionary idea.

These scientists would conduct public experiments in a coffee house or a “theater of science” in the company of like-minded gentlemen, who could all use their senses—and their reason—to agree on what had factually taken place.“ Their focus on demonstrable fact led to experiments in proto physics, chemistry, astronomy and biology, and, eventually, to the preeminence of experimentation.

The 17th century "theater of science"

Meanwhile, Michael Boyd, appointed RSC Artistic Director in 2002, was choosing early modern plays to be performed by RSC, and was interested in thematically challenging new plays as well. Then came the invention of professors Sonenberg and Henderson: the idea of co-teaching a class—providing students with the opportunity to research a pivotal period of intellectual history, the emergence of the modern form of scientific inquiry; and to bringing it alive by researching with an eye toward creating a play.

As drama, the idea had everything going for it. It drew on “making science” and “making theater” as kindred pursuits—as exemplified in 17th century Europe and in the contemporary student population of the School. In 2002 the project received a major commissioning grant from the Ensemble Studio Theater and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for plays about science, and a gift from Ken Wang, (a member of the MIT Corporation and a regular supporter of Shakespeare projects in the humanities and arts) that provided critical support in conducting the team-taught seminar.

Beyond disciplines

Professors Henderson and Sonenberg would seem the ideal teachers for the enterprise. Henderson, an expert in Shakespeare, Renaissance literature, drama and gender studies, has been active in the performance world. Sonenberg, a director who has developed new acting techniques, is a theater scholar.

“Janet and I are both interested in the intersection of performance and literary and historical context,” says Henderson. The two professors approach drama from different ends of the spectrum, but overlap.

“Janet is a scholarly theater person, one who reads a lot. I’m a literature person who’s had experience as a dramaturge,” says Henderson. “Text and performance are aspects of any piece of drama, and some people see those as opposed. But I sometimes have my students do scene work or even design costumes. We spend a lot of time thinking of the plays as literary works with intellectual and cultural history, and so we’re at the performance end of the literary spectrum.

“We’re not atypical of MIT professors. We think outside the disciplinary assumptions. We are primarily teaching non majors, which encourages us to think beyond the boundaries. It makes for a richness of approach.”

Enter the playwright

What remained was the unsolved matter of the playwright. Who to bring into this classroom cauldron, where initially, some students “condescended to the great minds of the past, whose experiments they considered ridiculous,” remembers Virginia Corless, a member of the seminar. A playwright of intellect, energy, and receptivity was called for, one who relished debate.

One of the chief goals of the project—part of the play-making but significant beyond the play—was to cultivate open mindedness, along with a deeper knowledge of human psychology and history (of science, philosophy, politics, ethics, and religion); all necessary to developing the play, and to becoming science leaders, and, one might say, citizens of the world.

Why not bring the playwright of “Pugilist Specialist” into the ring? “I first heard about Adriano through my friend, the actress Blair Brown, who loved his way with words and put me in touch with his agent,” says Henderson. As Sonenberg recalls Shaplin “had only written a few plays, but at 26 he already had a compelling theatrical voice. He was young and rough, and poetic. His language is funny and dense.”

Playwrite Adriano Shaplin went on a Cook's Tour of MIT

"Drew Endy handed him one of four brown jars the size of vitamin pill bottles, each with a different chemically derived base of DNA. In his hand was the stuff of life. He met with David Karger, a computer scientist, mathematician, and man of faith. They talked about belief in God and belief in numbers.”

Once Shaplin was on the team, Sonenberg and Henderson became ambassadors between Science and Theater, making the MIT rounds with the young director who had never written a play of science or history (but had majored in anthropology, he points out).

A "Cooks Tour" of leading science at MIT

“In the beginning, Adriano saw Science stripping wonder from the world,” says Sonenberg. “We introduced him to some of the most interesting scientists and mathematicians in the world. I took him to see Drew Endy, who handed him one of four brown jars the size of vitamin pill bottles, each with a different chemically derived base of DNA. On the labels was an A or a T or a C or a D. In his hand was the stuff of life. He met with David Karger, a computer scientist, mathematician, and Orthodox Jew. They talked about belief in God and belief in numbers.”

Henderson and Sonenberg next brought Shaplin into the classroom, where students—physicists, economists, mathematicians, engineers, brain/cognition scientists, some of whom were also literature and theater majors—had been researching and prepping for months

The Playwrite and the students

“I was baffled on a technical, scientific level, and they were baffled by what a playwright does,” Shaplin remembers. “I was walking into a think-tank that had been going on for ages. One part of our relationship was me listening to the discussion and asking questions—my mind is set-up so I have an instant sense of what can be told theatrically. The students wrote sketches to transform material into dialogue. We would come into a rehearsal space and jam. Like, Robert Hook; what did he look like, walk like, what were his gestures? Through gesture and the use of space we were able to capture something intangible. It was thrilling because the students were deeply engaged intellectually.”

Throughout, the class read voraciously, from a list that ranged from The Skeptical Chymist by Robert Boyle to King Lear by William Shakespeare to Hydriotaphia by playwright Tony Kushner—for starters. Shaplin also encouraged productive sleeping. “I cannot overestimate the value of dreaming; there’s a mysterious form of alchemy, collating and expanding on the history [that students were learning].”

Theater leaps emotionally and intellectually

“We were searching for ways to imagine something not thought of before, theater that leaps emotionally and intellectually in the way people do, so the audience ‘receives’ it whole,” says Sonenberg—author of “Dreamwork for Actors” and “The Actor Speaks”—describing her idea of the autonomous imagination.

“It was the most difficult class I ever taught,” she adds. “We were cramming knowledge into our heads. You could feel your brain growing. Every day we taught ourselves through reading and arguing. We brought people in to talk about stuff—historians and science writers. You can’t understand these 17th century scientists in a vacuum. Taxes are related to religion is related to politics is related to science.”

Slowly the play began to materialize, the students’ ideas and scenes forming a map for Shaplin’s journey, along with his conversations with Sonenberg and Henderson, and his work with actors; first the School’s students and later the RSC pros. By 2008 these pursuits were becoming a play.

Making connections between science and our humanity

Why this extraordinary theater-making project—requiring so much from so many people—when perhaps a good steady focus on reading Shakespeare might have taught how drama is constructed, alongside some reading of history, concentrating on the development of scientific ideas, to teach how the beginnings of the scientific method was once a radical idea?

Virginia Corless (MIT ’05) a Marshall scholar who participated in the seminar is an astrophysicist now living in Munich, doing post-graduate work at The Cluster of Excellence for Fundamental Physics in nearby Garching. Corless says that all the experience activated students’ imaginations, enabling them to enter the world of the dissenting scientists, and more closely consider their own prejudices.

“I find doing theatre valuable to scientists—maintaining the ability to imagine, and to make the connection between science and the most visceral part of our humanity. The class offered a chance to witness and to be involved in a complex new piece of theater—with research and collaboration, and workshop-type development—and to be able to take part in a piece that would get a major public showing.”

Corless, who has been acting since seventh grade, and who “did theater all through MIT,” remembers “learning about the plight of the English actors, cut off from their trade, their art, their livelihood when theater was outlawed.” She remembers the class imagining what it was like “to suddenly lose almost everything about your self, and to be forced, as an actor whose only voice was English, to flee to France.”

“In dialogue with each other and with Adriano—who wasn’t at all reverent toward science or scientists—young scientists who confront misunderstanding about science from the larger world [today] confronted misunderstanding in themselves toward their scientific ancestors.”

It is this contextual understanding, dependent upon deep knowledge—across time, culture, and class, nationality, occupation, and preoccupation—that the School offers MIT students and the Institute community.

“Intelligent Cause is all around us, and the Laws of Life are Miracles. Miracles once, were Mythologies, passed along by Men. Now miracles are Laws of Nature, and we need take no man’s word. We Virtuosi may step away, lift our hands, but these repeating Miracles sustain." — Robert Boyle (1627–1691), in “The Tragedy of Thomas Hobbes”

Exhilerating — on and off stage

The creation of “The Tragedy of Thomas Hobbes,” which involved young scientists, a daring young playwright, distinguished professors of literature and theater; and a company of superb British actors all immersed in the legacy and currency of deciding what is true, probably could not have happened elsewhere. Dean Fitzgerald, who attended the play’s premiere, observes that “The scholars of our School thrive in the MIT culture of excellence, creativity, and service to the world. They innovate in surprising ways to bring positive change to our world.

What I most loved about this play was the simultaneous fascination with science and art, physics and theater, during this period of English history. The actors demonstrated an extraordinarily nuanced appreciation for the lively, excruciating, and exhilarating experience of making something from nothing, whether on stage or in the laboratory.”

In London, the play was received by encouraging reviews from critics, and considerable enthusiasm from audiences.

Story prepared by SHASS Communications

Editorial team: Lynda Morgenroth and Emily Hiestand

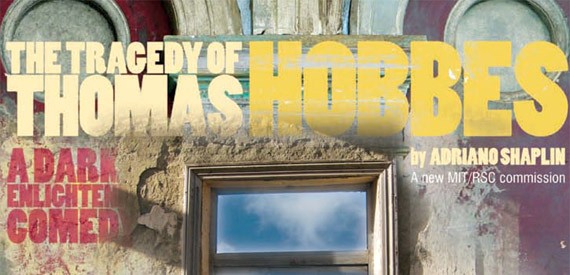

Photocredits: Top: Actor Jack Laskey as scientist Robert Hooke, London, 2008, Courtesy of the Royal Shakespeare Company; Middle: Detail, Thomas Hobbes theatre poster, London 2008; Potraits: L, Diana Henderson; R, Janet Sonenberg, by Richard Howard; portrait of Adriano Shaplin by Susan Brock, courtesy of Swathmore College