Medieval Tech

Profile of MIT historian Anne McCants

In her classrooms, MIT students gain insights—about history

and humanity—that bring more perspective and broad cultural

understanding to the decisions they will soon be making as

scientists, engineers, and global leaders.

A profile of the School's Head of History, MacVicar

Faculty Fellow,

visionary educator — and road trip adventurer

SPRING 2010 — BOOKS ABOUT THE AMERICAN WESTWARD MIGRATION, family road-trip adventures and the steady stream of foreign visitors through her family's sprawling Victorian house in Philadelphia are some of the early experiences that Anne McCants credits with nudging her toward life as a scholar of economic and demographic history.

Childhood affinities also helped shape her sustained enthusiasm for "old ways," including the once state-of-the-art medieval technologies that she introduces to MIT students as part of their education in history and culture.

Pre-industrial technologies

Anne’s knowledge of pre-industrial technologies is more than theoretical. Chair of History at MIT, MacVicar Faculty Fellow, and noted expert in research methods, McCants is also an adept at the spinning wheel. There is a beautiful, honey-colored one in her office in E51, and for this MIT professor, sheep fleece is on the list with computers as necessary academic gear.

In addition to the classes McCants teaches in medieval and early modern Europe and economic history, she is famous for two workshops—"Old Food" and "Distaff Arts"—which take place each winter during MIT's January Independent Activities Period (IAP).

"Old Food" is a hands-on workshop that teaches methods of preparing medieval cuisine, and culminates in a dinner gathering. "Distaff Arts" is a workshop in which MIT students learn the medieval textile technologies for processing and dying wool, complex and vital technologies for their time. "Distaff Arts" is a particularly intricate workshop operation to orchestrate, and McCants notes that "it is possible only with the help of two incredible assistants," Miranda Knutson (MIT ‘06), who is an expert on tablet weaving, and Margo Collett, an expert spinner and chief dye-pot mixer."

In her medieval history classes, McCants shows students that the quality of a society’s cultural production is profoundly related to its economy; and that potential genius can be nurtured by a healthy economy, or stymied by extremes of inequality and poverty.

Medieval tech

In the land of "mind and hand," MIT students flock to these challenging, hands on workshops—both for the extreme creativity (make your own hooded cloak!), and for the intellectual challenges raised by examining Medieval technology. One question that emerges for example: How did a predominantly agricultural society produce the technically and aesthetically sophisticated cathedrals of the Gothic movement? (By way of a hint, McCants suggests considering the impact of a flourishing, spatially diversified, and technologically innovative urban textile industry.)

Both McCants’ workshops are labor intensive by design, to promote an understanding of medieval history and to demonstrate the value of the labor performed, often by women and children. McCants also designs her workshops to provide opportunities for students to grow; the workshops unfold in a studio atmosphere that makes it easy for students to share stories, ideas, and experiences along with the collaborative work.

For her Medieval workshops, McCants is scrupulous about using only authentic materials. For the textile course, she provides sheep fleece, which, as she explains, must really, ideally, be filthy sheep fleece, which best demonstrates the human industry and technology once required for making textiles from raw materials. For the "Old Food" workshop, she allows only era-correct ingredients into the kitchen: turnips, for example, but not the rutabaga, which is a modern hybrid unknown to the medieval table.

MacCants adds “Alas, we make no tea, as in the fifteenth century, tea had not yet made its way from China to Europe.” The one additional protocol for the food selection is not exclusive to the Medieval kitchen: “We only cook food that I like,” says McCants.

International Philadelphia

McCants was born in Philadelphia, and although her family moved to the west coast when Anne was ten, she remembers life in Philadelphia vividly. There, her father was a professor at Temple University, her mother a nurse, and the family’s rambling home functioned as an informal, international dormitory for countless travelers.

“My parents were involved in University Christian Fellowship and worked especially with international students,” McCants explains, “so there was an endless parade of people from all over the world through our house. I remember once going with my parents to the port of New York to pick up a family of missionaries from Morocco. What amazed me was how intensely packed and crowded the scene was—my first sense of the mass of people moving about the world.”

The flux of peoples, as well as life in a melting pot Philadelphia neighborhood would spark McCants's fascination with forms of social organization and multiple cultural perspectives, an intellectual quest that led to a book about the social welfare systems of the sixteenth century Dutch Republic.

Her research continues to focus on issues in historical demography, early modern trade and consumption, and the standard of living in pre-industrial Europe.

Civic Charity in a Golden Age: Orphan Care in Early Modern Amsterdam, is a study of the consequences of rapid economic development and urbanization in the Netherlands—forces that made it difficult for families and local communities to care for those in need as they had before.

Wanderlust

Other indelible experiences for a budding historian were the automotive forays led by her father, Professor Norman Conger (who teaches now at Diné College on the Navajo Nation). "My father had, still has, a terrible case of wanderlust, and was always taking us on trips to explore the world,“ Anne says fondly.

“Dad would just get us in the car with some jars of peanut butter and water, and off we'd go—pulling over, sleeping in rest areas, or sometimes driving all night. We didn’t make firm plans for where to stay, but we almost always carried a canoe on the roof of the car on the grounds that you just never knew when a good river was going to present itself. Dad had always done a lot of reading beforehand about where we were going. He was forever reading up on things—natural history, human history, roadside geology, rapids, trail networks, flora and fauna, weather, topo maps, etc.—and he has a book for every possible cool place to visit or fact to know about."

Anne has inherited the road adventure gene. “I’ve crossed the country, round trip, by car 30 times or more," she says, "many times with my parents who are still part of our summer expeditions. I have been in every state, and have driven to all of them except Florida. The McCants family list of favorite places includes the White Mountains in eastern California, home of the ancient Bristlecone Pine forest; the Wind River Range in Wyoming; and Wall Drug Store in Wall, South Dakota. Reflecting on the record, McCants muses, "Probably our most daring road trip was driving across Death Valley National Monument Park—in August."

"My father had, still has, a terrible case of wanderlust, and was always taking us on trips to explore the world. We almost always carried a canoe on the car on the grounds that you just never knew when a good river was going to present itself."

Mentors

Primed by her early experiences, Anne’s life in history began to accelerate at Mt. Holyoke College, where she compiled a curriculum akin to a quadruple major—in Economics, History, Religion, and German. She also took classes with Professor of Religion Robert Berkey who became, McCants says, “a huge influence on my intellectual development."

"He drummed it into our heads that we had to approach everything with compassion and intellectual integrity. Professor Berkey considered our entire development as human beings as part of his purview. He taught us to be concerned with the human condition; that we were accountable for making good decisions. Two times each semester, he invited us to his house, where we had tea in porcelain cups and talked about the world. I remember his living room—with Persian rugs, chairs with lace doilies—and the mutually supportive interactions between him and his wife, who was clearly an intellectual partner."

Another mentor, Bob Schwartz, in the Mt. Holyoke History Department, “introduced me to the idea that I could do both history and economics; that I could combine disciplines.” He also catalyzed a quiet epiphany for Anne, when he packed the eight students in his “New France” course in a rented van and took them on a trip to Quebec.

Stepping into another world

In Quebec, the class visited the Ursuline convent, founded in 1639 and the oldest institution of learning for women in North America. There Anne came upon the convent archivist, “an ancient, tiny, cloistered nun in her 90s, absolutely formidable about protecting her precious documents.”

“She showed us their original Charter with the seal of Louis XIV—a large flat piece of yellowed parchment under glass, with seventeenth century script and a wax seal at the top. It was my first experience with a tangible piece of history. At that moment, with that nun in that chamber, I stepped into another world. It was like being in the presence of something sacred. The old nun and the old charter—they showed me that someone could love, palpably, a historic document. Her intense appreciation for the past, slipping imperceptibly into her present was a revelation to me.”

"She showed us the original Charter with the seal of Louis XIV—a large piece of parchment under glass, with seventeenth-century script and a wax seal. It was my first experience with a tangible piece of history. At that moment, I stepped into another world."

McCants went on to earn a Masters in Economics and PhD in History, at UCLA and Berkeley respectively, and developed an expertise in the emergence of northwestern European society in the late Middle Ages and Early Modern period, especially the sources and stimulants of economic growth, the development of social institutions, and the distribution of resources across social and geographic boundaries.

She accepted a position at MIT in 1991, and arrived in Cambridge with her husband Bill (now a civil rights attorney). McCants has found herself very much at home at MIT, drawn to the rigorous intellectual atmosphere, the open-mindedness of students and faculty, and by the Institute’s strong “tinkering component.” Recognizing the distinctive, even unique, opportunities for teaching history at MIT, she has shaped her courses to emphasize and expand the understanding of technology across time and place.

She is keenly aware that MIT students’ understanding of history can increase greatly the perspective and wisdom of the decisions they will make as scientists, engineers, and thought leaders. In part, she uses medieval history to reveal to her students that the quality of a society’s cultural production is profoundly related to its economy; and that potential genius can be nurtured by a healthy economy, or stymied by extremes of inequality and poverty.

What's at stake

“It takes broad societal opportunity for genius to fully emerge,” McCants says, “and it is my hope that our students will go into the world with a changed sense of purpose, with an understanding of the richness and diversity of human experience and a passion for shared opportunities. Our students are extremely energetic and clever, and for the most part will find success in this world. I want to help them appreciate the value of helping others to find success too.”

Like Professor Berkey, McCants in turn considers the development of her students as whole human beings to be part of her academic purview. She, too, teaches the need to approach every intellectual and personal situation with compassion and integrity, and to be fundamentally concerned with human well-being.

“Some of our students will be motivated to build,” says McCants, “and others to create works of art; some to do scientific research, take political action, others to pursue poverty eradication—as doctors, economists, writers and policy wonks. I’m not fussy which of these tacks they decide to take in life, so long as they come to appreciate what’s at stake for all of us.” •

More about Anne McCants

History Faculty

Civic Charity in a Golden Age

News

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications

Editorial and Design Director: Emily Hiestand

Writers: Emily Hiestand, Lynda Morgenroth

Photography: Portraits of Anne McCants by Richard Howard

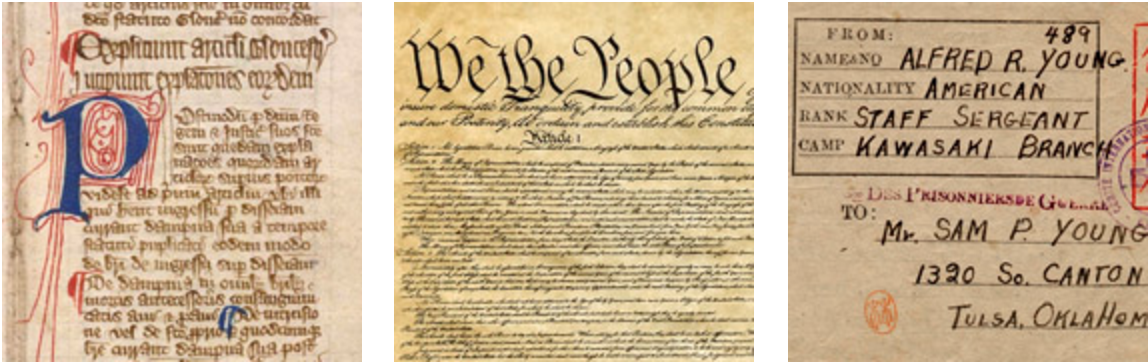

Photographs in center: Details of documents—the Magna Carta; the US Constitution; letter from a WWII POW