Profile | Dr. Bette Davis

For two decades, Dr. Bette Davis, as director of the HASS Education Office,

has helped the Institute administer its undergraduate requirement for courses

in the humanities, arts, and social sciences. Bette's knowledge of the nuances—

and the potentials—of the requirement is now legendary. As we celebrate Bette's

profound and lasting contributions to the lives of thousands of MIT students,

here is a profile of the woman who is fondly called "The HASSologist."

ONE SPRING DAY in 1969, a year when America's college campuses were erupting with political turmoil, a young woman from rural South Dakota was making her way to her office at Morehouse College, the famous, historically black, and all male college in Atlanta, Georgia.

She had a German class to teach that afternoon, but while crossing campus, came suddenly upon a large group of protesting students, who had, she gradually realized, occupied the administration building. In addition, the students (who, it turned out were holding captive the entire Board of Trustees) had also spray-painted a slogan on many of the college’s red brick buildings. The message was clear and stark: “An All-Black University for Blacks!”

The new teacher hesitated. She was not black, she was white. Should she proceed on to her office and classroom? Should she return home? Was this teaching post a good idea after all? As she stood deliberating, one of the protesters—a friend of a student in her German class—popped his head out a third floor window of the administration building and waved down to her with a warm smile.

“Good morning, Miss Davis,” he called out.

Buoyed by the friendly, courteous gesture, Bette Davis walked on to her office, and to her classes as usual. The ability to earn the respect and affection of students that already characterized the young Davis has continued to inform and grace her work in education ever since.

Expanding horizons

In Atlanta, in her early twenties, Davis was already far from where she grew up, on her family’s farm on the windswept Dakota plains, and started on a journey that would take her to Germany, around the United States, to China and other lands, and to 02139. Here at MIT, Dr. Davis has used her expansive perspective, expertise, and warmth to help thousands of students expand their own intellectual horizons.

“Bette believes very deeply in the fundamental value in preparing MIT

graduates to lead in society. She truly understands the importance of

global opportunities for undergraduates. As an intellectual who has had

significant experience abroad herself, Bette knows how transformative

these opportunities can be.”

— Malgorzata Hedderick, Associate Dean for Global Education

An MIT education is designed to give all undergraduates (whatever their major) a strong grounding in the humanities, arts, and social science disciplines. Through the classes that complete the HASS Requirement, the Institute gives all MIT undergraduates a multi-dimensional education, with fluency in the several major traditions of knowledge. Fulfilling the requirement, MIT students gain the cultural and historical perspectives, and critical thinking and communication skills that help them take on leadership roles.

For two decades, Dr. Bette Davis has helped the Institute administer the HASS requirement. Her deep knowledge of the logistics, nooks, and crannies—and potentials—of the HASS requirement is now legendary among MIT faculty, staff, and students alike.

Kai von Fintel recalls that long before he became Associate Dean of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, he “had already had heard about the mythical Bette Davis—the person who knew everything about the HASS Requirement, and was the ultimate authority on all rules and regulations.”

Thinking of Bette’s role in keeping the HASS Requirement ticking at MIT, Peter Child, Professor of Music, says, "Bette is the spring that makes the clock work!”

Rightly dubbed the “HASSologist,” for knowing the HASS requirements inside and out, backwards and forwards, Davis also knows how to guide students and faculty as they apply the requirement in particular cases and courses of study.

Working closely with Bette for the past two years,

I have realized that what motivates her is a deep

and abiding concern for the welfare and progress

of our students.

—Kai von Fintel, Associate Dean,

School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

Chaplain to the Institute Robert Randolph recalls a student in his office with an urgent question about her HASS coursework timetable. The particulars were beyond even Randolph, whose credentials include serving as a Senior Associate Dean for Student Life. “Of course,” he laughs, “my immediate reaction was to call Bette, and sure enough, we had the answer in 30 seconds.”

In addition to serving as a one-woman Wikipedia for HASS, Bette has the ability to communicate her vast knowledge to confused and sometimes frazzled undergraduates who are trying to plan, complete, or rearrange their approach to their HASS courses.

Kai von Fintel, the School’s Associate Dean says, “Working closely with Bette for the past two years, I have realized that what motivates her is a deep and abiding concern for the welfare and progress of our students.”

Malgorzata Hedderick, the Associate Dean for Global Education agrees. “Bette’s responses to students have always been very thoughtful, caring, and very thorough,” she says. “In addition, they sparkle with good humor."

The importance of being . . . surprised

Davis’s commitment to guiding MIT students springs from a principle well demonstrated in her own life: namely, that the most unexpected and surprising subjects may be the ones that take you where you want to go.

At age eighteen, however, spurred by South Dakota State University’s foreign language requirement, Davis decided to study the language that had once confused her.

And then, she says, "Ich habe mich in die deutsche Sprache verliebt. I fell in love with the German language. It is a beautiful language and a logical language, both in the pronunciation and the grammar, and I was attracted by the beauty of the structure."

Davis received the German equivalent of a Fulbright

and studied for a year at the University of Freiburg.

From there, she traveled behind the 1960s Iron Curtain

to Leipzig, Weimar, Naumburg and other East German cities.

After graduating, Davis received the German equivalent of a Fulbright, to study for a year at the University of Freiburg. At a time when East and West Germany were still divided, Davis was able to travel with a friend to Leipzig for the Bachfest, to Weimar, where Goethe had written, and to Naumburg, site of the famous Cathedral, and several other East German cities, where she saw the vibrancy of cultural and political life, as well as the restrictions, behind the Iron Curtain in mid-1960s.

Upon return, she earned a Masters degree in German Language and Literature, taught at Grinnell College, then Morehouse, where she stayed until Nixon’s election, an event that prompted her to set forth again to Europe, where she taught in a West German Gymnasium.

It was there that she discerned her true calling, to work with students as a counselor and advisor. Upon return to the US, she served as director of the Office of International Education at UMass Boston, while earning a doctorate in education from Harvard University. She arrived at MIT in 1989, and in 1990 became director of the HASS Education Office.

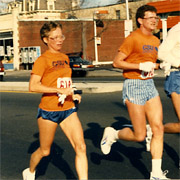

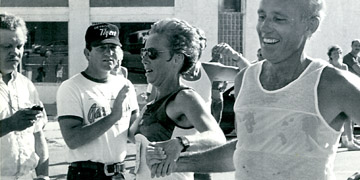

L: Boston Peace Marathon, November 1985; first place, Masters Womens Division (3 hs, 12 min);

R: Bette and her brother Ron, crossing 10K finish line together, July 4, 1988, Gregory, South Dakota

A lifetime runner—from childhood to the present day—

Bette has several records in her trophy case, among them

the course record for her division in the Mt. Washington Road Race.

The "orchids" and other discoveries

Over two decades at MIT, Davis has seen countless examples of how the Institute’s humanities, arts, and social sciences curriculum changes students lives, expanding their ways of understanding and interacting with the world.

“I see over and over that our students discover an area of knowledge, or a way of thinking, that turns out to be absolutely vital to their lives and career paths—and which they experienced thanks to the broad educational requirements the Institute has established.”

Similarly, Jesus Guardado, a junior majoring in Materials Science and Engineering, who says he has counted on Bette for guidance “many, many times,” credits the HASS requirement for directing him to new interests, such as religious studies.

Deborah K. Fitzgerald, the Kenan Sahin Dean of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, underscores the point, saying, "For Bette, each and every student has the potential to change the world, and she tries to instill in them an ambition to always do more, to go farther. She wants every student to reach their potential by taking advantage of the myriad opportunities to learn and grow intellectually. Bette's own zest for life is a wonderful model for them!"

No profile of Bette Davis would be complete, of course, without a note about the name she shares with the great Hollywood actress of the 1940s. Bette says that she has been asked about her famous name throughout her life—often daily!

At MIT, there are also many big fans—of both Bette Davises. But only one Bette Davis has been the star HASSologist for the Institute, and only one has helped guide thousands of MIT students toward more expansive and successful lives.

The sentiment of the School community, of thousands of MIT alums, and the Faculty and Administration of the Institute as a whole is well summed up by Associate Provost Philip S. Khoury. Reflecting on Davis’s sustained and enormous contribution to the Institute, the former SHASS dean says simply:

Bette and her paternal grandfather, on the Davis farm, South Dakota, 1947

Writers: Stephanie Schorow, Emily Hiestand

Photographs: Portraits of Bette Davis by Richard Howard

Davis family photographs courtesy of Bette Davis